TYPICALLY, says Nick Chandler, community schools coordinator at Buena Vista Horace Mann K–8 school in San Francisco, the family power structure in schools tends to fall within families with privilege. “Families with income, families with access, families with time,” he explains.

At BVHM, such families are few. A dual-language Spanish Immersion Community School in the city’s Mission District, BVHM enrolls about 600 students; in 2021–22, 86% identified as Hispanic/Latino, 64% were socioeconomically disadvantaged and 63% were English Learners.

BVHM Community Schools Coordinator Nick Chandler

“To ensure that we had authentic partnership with our families of students who needed the most support, we’ve had to be really strategic about how we engage families and set up shared decision making to hear the voices that often go unheard,” Chandler says.

The strategy involved continuous outreach, listening to and encouraging leadership from families — especially monolingual Spanish-speaking families — and responding to their needs. This included creating the Stay Over Program about five years ago, which allows unhoused San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) families to sleep at the BVHM gym and receive case management services to support their eventual housing.

Housing remains one of the major challenges BVHM families face. Other immediate challenges identified by BVHM families are immigration and mental and physical health needs. “Basic needs supports have evolved over time. They’ve been a direct result of that family voice, of that student voice,” says Chandler.

“Our kids aren’t on the streets”

It’s almost 6:30 p.m. on a late spring evening, and several families are already standing patiently outside the BVHM gym, backpacks and bags in hand, waiting for the doors to open at 7. Inside, workers are setting up partitions that give each family a modicum of privacy where they can unroll bed mats and settle in for the night. Bathrooms, with showers, are at one end of the gym; at the other end is the room where families enter, sign in and eat dinner. Students can use the dining tables for homework.

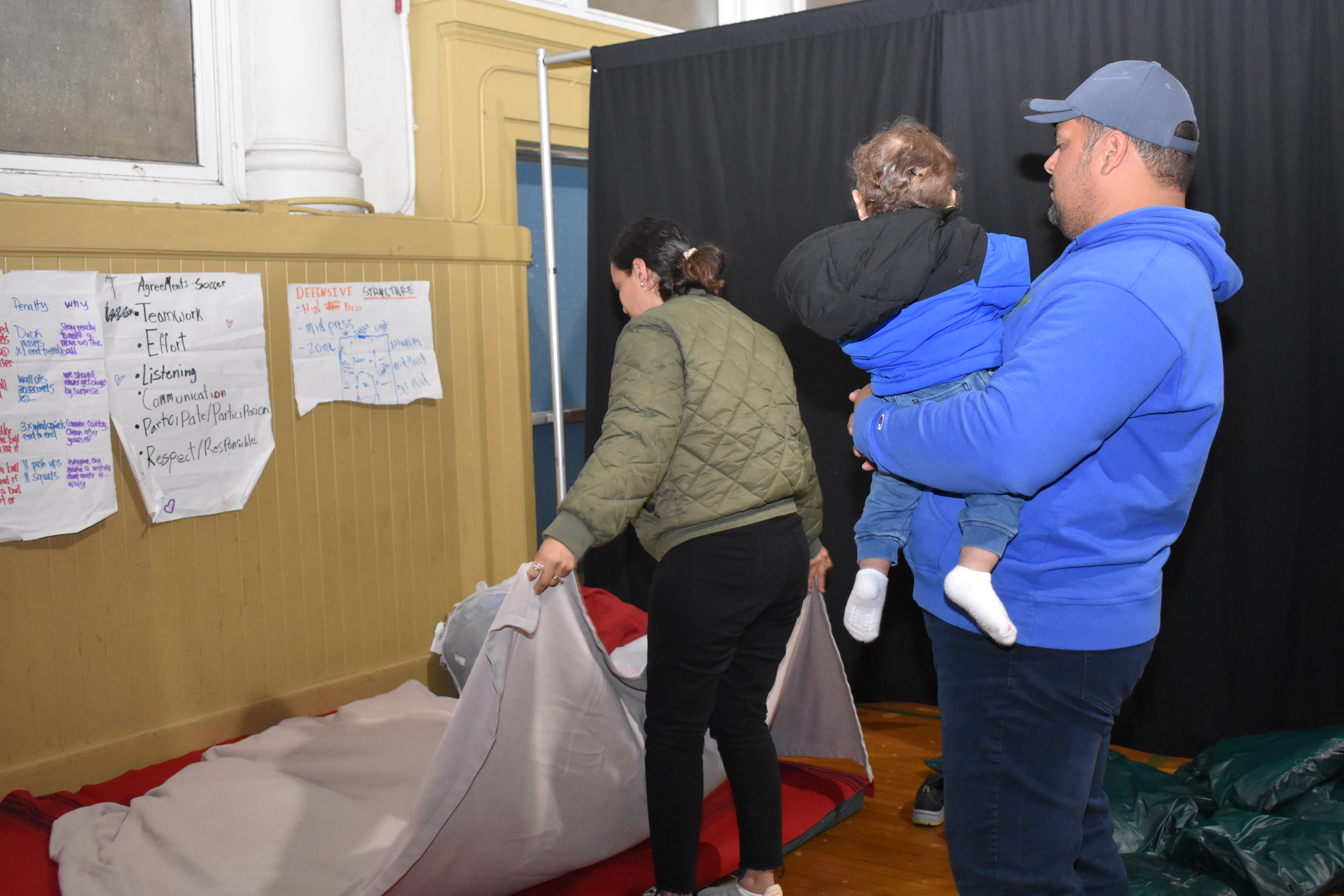

The Navas-Torrez family prepares their beds at the Buena Vista Horace Mann school gym

Some 70 people will sleep at BVHM tonight. They’ll eat breakfast before leaving the gym by 7 a.m.

“When we arrived in San Francisco, we didn’t have a place to live, so we were living in the streets,” says Mayel Navas, who with her husband Saul Torrez has been staying at the gym with their four sons — one of whom is still in a stroller. “We met a friend who told us about this program. We feel super grateful.

“[The Stay Over Program] is important because our kids aren’t in the streets. They have a place to be after school, a place to study. For them it feels like a second home.” —Parent Mayel Navas

“This place is important because our kids aren’t in the streets. They have a place to be after school, a place to study. For them it feels like a second home.”

“We came to the United States because our country [Nicaragua] was going through a time of social-political unrest and there was a lot of government persecution,” Torrez says. “We don’t have the words to say how much we appreciate [the Stay Over Program].”

A joint use agreement allows this S.F. Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing program to be operated on school district property by the nonprofit Dolores Street Community Services.

Shared decision-making in the contract

While each community school is unique, their common denominator is shared governance among educators, students, families, administrators and community partners. By achieving a truly equitable model of shared decision making and listening to all stakeholders, BVHM’s Stay Over Program and other initiatives are meeting vital needs that have led to healthier families, more engaged and productive students, educators who are able to teach and nurture children to their fullest potential, and stronger connections to the community.

CTA and local chapters are working in partnership with the state, school districts, students, families and community to help grow and support California’s community schools, bolstered by the state’s nation-leading $4.1 billion investment. A primary focus among locals is to ensure shared decision making is contractually codified — necessary for all stakeholders to be heard and participate as equals.

“UESF has been working on three different levels” with SFUSD, says Cassondra Curiel, president of United Educators of San Francisco (UESF). “The first is in bargaining a contract that would codify community school language and the shared decision-making protocol.”

United Educators of San Francisco President Cassondra Curiel

The second is UESF’s agreement with SFUSD to help select and hire a district director for community school implementation, “working closely with them to make sure we are in close alignment with state guidance”; the person hired has a background in community nonprofits. Third, the local is involved at the ground level with UESF Secretary Leslie Hu, who is on full-time release as UESF’s Community Schools Initiative Coach.

“It’s a position we felt was important to have to bring up member ‘Community Schools IQ’ and to help directly at sites as they navigate the community schools process,” Curiel says. Hu works with educators, school staff and administrators.

Curiel adds that for “our 6,500 UESF members, learning about community schools is an ongoing process. We’ve been working to educate and elevate this — not just the application to become a community school, but what it means to be part of a community school.

“UESF is very intent on making sure that community schools is not a trend. This is not a moment. This is a cultural shift.” —United Educators of San Francisco President Cassondra Curiel

“At school sites operating with a shared decision-making model where families are actively invited to help make decisions and embraced and empowered, we’re seeing a big impact…. At one elementary school, the administration and educators were trying to seek an intervention to raise reading and math scores. [Stakeholders] devised a plan collectively to shift schedules and carve out the school budget for extended hours so educators could work with the after-school program [toward] those math and reading goals. It spread into what families engaged their students on at home as well.”

Curiel points to multiple other examples of community schools’ collective decision-making that have successfully addressed challenges at individual sites, and made students and families feel like they are represented and have a voice.

Bilingual teacher Marcos Espino with 7th grade students.

Empowering parents to speak up, get involved

Boisterous students congregate in the BVHM yard at midday, some eating lunch and talking with friends, others engaged in games. The administrative offices also bustle with students and educators. In contrast, students in Marcos Espino’s 7th grade class upstairs quietly work on assignments. Espino, who grew up in the Mission District, moves from table to table, speaking in Spanish.

BVHM Principal Claudia DeLarios Moran is a native San Franciscan whose children attended the school before she stepped into her current role. She notes that BVHM has been a community school since its inception in 2012; she expects the new funding and protocols will amplify the school’s resources and programming. While DeLarios Moran was BVHM vice principal, she worked to pilot the Stay Over Program.

BVHM Principal Claudia DeLarios Moran

“The shelter started out of desperation during a particularly rainy winter,” she recalls. “A number of families asked us directly if they could stay overnight. We quickly realized that that is exactly what we should do.

“Our true north is ‘What does every child need to be self-regulated enough to learn today’s lesson?’ The community school approach allows us to wrap ourselves around a child and their family’s need so we can get them there.”

“What does every child need to be self-regulated enough to learn today’s lesson? The community school approach allows us to wrap ourselves around a child and their family’s need so we can get them there.” —BVHM Principal Claudia DeLarios Moran

This results in students who flourish academically and on a social-emotional level — and parents who are empowered to speak up, get involved and become leaders themselves. “We now have parents who serve on important boards within SFUSD, for example, on the community advisory council for special education. We have parents that are extremely adamant about demanding the kind of facilities our students deserve — having conversations not even at the district level, but at the state [level].”

Engaged educators and families

Chandler says the development of the Stay Over Program taught BVHM administrators and educators a lot on how to engage families — how to build authentic partnerships and shared decision-making structures. “We surfaced flaws in how we were governing our school and how families participated. By having those hard conversations and

building programming that was responsive to the highest needs as defined by our families, we were able to disrupt that pattern. It shifted our programming and our focus and intention. It shifted our goals and our mission.

“It forced us to really articulate ‘Why are we here? Who are we here to support? How are we going to be inclusive in that work?’”

Current needs, according to surveys and data, center on mental health. As Chandler puts it, “How do we deliver trained, qualified bilingual mental health professionals to our students and families that need it?”

BVHM educators, he says, are fully aligned with the community school’s objectives, particularly around family involvement. “We have intentionally brought in teachers that have the vision and philosophy of teaching that includes the family. Teachers are always strong advocates for families at our site.”

Educators city-wide are working hard to make community schools work long-term, says Curiel. “UESF is very intent on making sure that community schools is not a trend. This is not a moment, but instead this is a cultural shift, a movement from traditional schooling to a community schools model that includes so much community input, so much student, family, educator [input] that the school itself is fundamentally changed to be a place where families and students feel they are part of the entire day.”

To view videos on BVHM Community School and its Stay Over Program, visit youtube.com/californiateachers. Learn more about CTA and community schools and read previous coverage at cta.org/communityschools.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment