EACH COMMUNITY SCHOOL is different — they have to be. The community school model draws on the unique strengths of a neighborhood to address its students’ unique needs. This is particularly clear at bustling Hoover High School in San Diego, one of five designated community schools in the San Diego Unified School District last year (another 10 have been designated to begin their transformation this year, 2023-24).

Hoover, with 2,136 students, is situated in the most ethnically diverse neighborhood of the county, City Heights. Many students and families are newcomers to the United States; 100% are eligible for free and reduced-cost lunch. “We have over 40 languages represented among our families,” says Candace Gyure, the school nurse. The demographic breakdown, according to Hoover’s website, is 75% Latino/Hispanic, 12% Asian, 9% African American, 1% White, 22.3% English Learners and 7.5% Homeless Youth.

Kyle Weinberg

“Hoover High serves one of the highest need communities in San Diego,” says Kyle Weinberg, president of the San Diego Education Association (SDEA), which with CTA has long advocated for community schools. “Community schools are a great way to identify the unique needs of a community like City Heights, and also to transform how we do education within the classroom, have more culturally sustaining curriculum — more community-based curriculum, real-world projects, collaboration with community organizations on the issues that are facing our communities.”

In class with Chase Fite, Hoover’s community schools site coach and AP Government teacher.

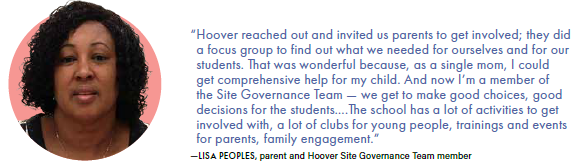

Like many schools, Hoover offered various services — including a wellness center, mental health center, etc., before officially becoming a community school. But the community school structure brought shared decision-making among students, families, educators, district and community as well as a data-oriented approach to assess needs and assets. This has resulted in more accessible, coordinated services, and resources directed to or developed for specific needs. The structure has also allowed for enhanced partnerships with community organizations and stronger connections among the school, students and families.

“It’s a long-term approach,” Weinberg says. “Addressing [social, mental, physical] needs now will impact such things as academic performance, social emotional learning, and attendance in the coming years.” Here are the elements that Hoover has put in place and continues to refine:

Community Schools Site Governance Team

Composed of 10-12 elected positions who have an equal voice and represent all stakeholders: students, parents, community, union educators, district leaders. The team oversees the working group subcommittee, composed of about 22 people who work on strategy and communication, assessing needs and assets, developing protocols and processes, etc. SDEA has a precedent for shared governance won in a contract fight in the 1990s — see page 38 for details on how key this is to the community schools model, and what it requires.

Involvement of all stakeholders

- Parents: “Convincing parents that this is not district-driven but truly collaborative [is hard],” says Richard Gijon, Hoover High’s community schools coordinator. “But I can see them get excited when I ask, ‘What are the top priorities for your students’, and we actually listen to them and ask them to work with us and be part of that process.”

- Students: It’s the same with students, Gijon says. “To see their excitement has been amazing — ‘not only are you asking me for my voice, but you’re actually telling me what you’re hearing.’”

- Daniela Silva (pictured and quoted above) graduated from Hoover in June and was a member of its community schools working group subcommittee. She spoke in a Hoover video presentation about how she and other students have been able to witness the many impactful changes at the school in recent years, including the community garden and Hoover Market. Watch the video at tinyurl.com/3fyrkue4.

- Educators and community: A big part is played by the community schools coordinator and site coach, says Chase Fite, Hoover’s site coach, “You need someone who’s trusted, [who can convince others that] this is something that is going to improve our site and improve the life of the students as well as all people surrounding our community.”

People power

It takes a village, of course, but specific people in specific roles are crucial to success.

RICHARD GIJON, Community Schools Coordinator. Gijon works full time to coordinate all student and family support services and creates an environment that helps support student achievement and wellness. “The students and families in our community dictate what I do. Some days a family comes in in crisis [over] issues of food security, housing, and I connect them to the resources we have. Sometimes it’s mental health….We had all these resources [before, but] it was a little disjointed. Part of my role [is] trying to get all these programs to develop a plan to engage all our students.”

CHASE FITE, Community Schools Site Coach. The AP government teacher spends one class period on community schools work, including needs assessment and data collection and analysis; implementing expanded and enriched learning; and developing and implementing collaborative leadership and decision-making protocols and structures. “A site coach helps build up the relationships and the onboarding of the staff as well as the community partners on site. I’m also developing collaborative leadership protocols and structures and helping implement them.”

SITE GOVERNANCE TEAM, see previous page. The site team approach, with its shared governance, was actually established in the SDEA contract in the 1990s to ensure members’ ability to democratize the workplace, determining such things as school schedule and dress code. (Note: The team is different than the School Site Council.) Community schools’ work builds on these existing decision-making bodies.

SDEA AND MEMBER EDUCATORS, a critical force in supporting community schools as drivers of equity, democracy and engagement among students, families and community — and educators.

Medical, dental and mental health services are available to students at Hoover’s Health Center.

Assessment of needs and assets

Hoover sought answers from all stakeholders: What does success for students and the school look like? What are the barriers to achieving it? What strengths — including from parents and community — can we draw on to address the challenges? Through surveys and focus groups, the top three needs, by group:

- Students: Working bathrooms (last year there were only 2-3 working bathrooms per gender for 2,136 students; some were closed due to maintenance, vandalism, drug usage); health, including improved food; and attendance (not just chronic absenteeism, but security and being consistent with school rules).

- Parents: Academic enrichment and tutoring, mental health, opportunities for students to connect socially.

- Educators: Attendance (including tardiness), mental health supports, student engagement. Mental health services and supports were also among the top needs for students and parents.

Data collection:

- Students: “We reached 83% of the student body through surveys and focus groups,” Fite says. “We audited the information to ID those students we have no data on — such as the chronically absent. Then we created a system to engage in home visits with those students and parents to ID a unique stakeholder group who have particular needs, assets and wants.”

- Educators: 92% of certificated staff completed surveys. Overall, an aggregated 74.5% of classified and certificated staff participated in focus groups.

- Parents: “By June 2023 we will have reached 75% of parents,” says Gijon. “We started multiple focus groups in January 2023, in Spanish and English, electronic and paper surveys in six different languages. Every day at drop-off we were asking ‘Have you done your survey? We want your feedback.’ We were also hitting all our big events, and asking community partners who have parent meetings to pass along the survey.”

Exploration of potential solutions

Use the data to determine the needs and assets; the working group with input from others are coming up with ways to use the assets to address the needs, as well as create other assets or bring in services for specific needs. This is an ongoing effort. Some early outcomes:

- Class projects: In a first-semester U.S. History class with juniors, Chase Fite’s students worked on a public health advocacy project using the community schools framework. “For me, this was a rough draft/dry run for implementing the framework before doing so with other stakeholder groups,” Fite says. Focusing on the bathroom issue (see previous page), students developed a needs and assets assessment survey and pushed it out to the school for completion, and created a website where they analyzed survey data, presented historical context of the issue, explained the science behind why the issue is harmful to the community, and put forward philosophical and ethical theories that they used to argue whether or not to act on the issue.

Students then presented their findings to other classes, teachers and administrative leaders, and engaged in collaborative dialogue about solutions the community would want to see implemented.

In a second semester AP Government class, Fite had students refine the working group protocols for determining and implementing solutions. This class found that the root cause of the bathroom issue was vandalism due to lack of student ownership, and that a student art installation, for example, could allow them to regard the space as their own and discourage vandalism. Another class found the root cause to be bathroom drug use and vaping, which cause other students to avoid bathrooms. Students suggested those who are caught using drugs take part in a Social Justice Academy-run student mentoring program with a focus on restorative justice.

- Next wave of planning: The district is paying for a two-week 2023 PBL summer institute where the working group and other stakeholders are delving deeper into the needs and assets data to come up with solutions. For example: creating a mental health campaign through Hoover’s Health Academy, as data shows more than half of students don’t know how to access the school’s mental health services; and dedicating community schools funds to more supports offered by community partners, such as those involving mental health.

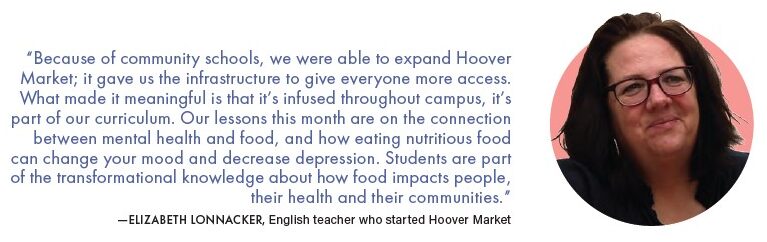

These new efforts around mental health build on current/earlier initiatives by educators such as Ellen Hohenstein, whose students work on campus-wide projects to bolster mental health awareness and interventions, and Elizabeth Lonnacker, whose students created mental health public service announcements for the school.

- More opportunities for engagement: “Parents want the school to become that hub where they can have meaningful relationships with each other and with other positive adults,” says Gijon. To that end, he and Hoover have further developed resources and events for students focused on social connections, and for parents/families focused on health and wellness, government and community programs, etc.

A mural on campus.

Strong partners

In addition to community partners at individual school sites, a steering committee at the district level includes representatives from San Diego State University, community organizations, educators, high school students and others who meet monthly, oversee work groups and provide recommendations.

Students working in Hoover’s garden.

SDEA is a member of the San Diego Community Schools Coalition, which advocates with parents, community organizations, school board members and at the bargaining table to elevate parent and educator voice in the decision-making process.

Hoover High School maintains an extensive network of community, district and city resources for students and families in multiple arenas, including legal services, food and shelter, health and wellness, tutoring and more.

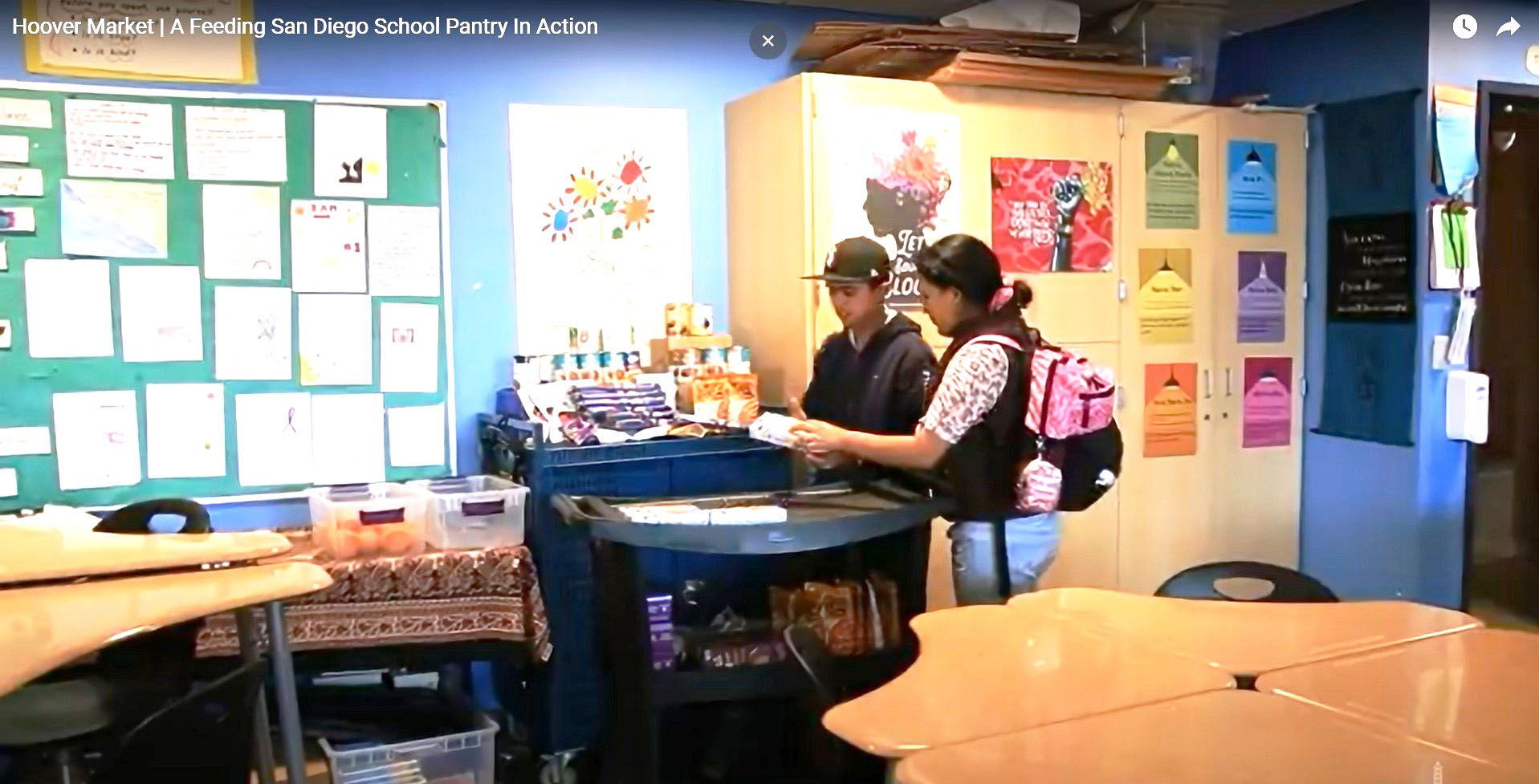

Students stock classrooms with items requested by teachers for their students – a variety of healthy snacks and other foods.

Hoover High’s Featured Services, Programs

Based on its unique needs, Hoover High School has integrated a number of successful student and family supports, among them:

- Hoover Market, in partnership with Feeding San Diego; a variety of foodstuffs are free to students and available in classrooms as well as at the market. Special needs students and Hoover’s Health Academy students stock and distribute foods; educator and chef Tina Luu teaches nutrition and culinary arts with fresh produce and other ingredients from the market, and the food distribution center is open to the community twice a month. The market was started by teacher Elizabeth Lonnacker in 2022, after she noticed students were taking snacks she had in a classroom cupboard as “food for the weekend.” She used project-based learning with students to help bring the market to fruition. The initiative addresses some of the student absentee problems as well, as many students hold parttime jobs to help their families pay for food, rent, etc., but whose jobs interfere with school. (See a recent video about the market at tinyurl.com/2jc5s8sm).

- Organic school garden project

- After-school programming with strong parental input, focusing on arts and music, science, etc.

- At-risk student support through Youth Empowerment

- Health center, offering health assessments, general assistance with chronic illnesses, immunizations, vision and hearing screening, family planning services, dental services; some services through La Maestra Community Health Center (on campus)

- Mental health supports, through Mending Matters, offering drop-in and crisis services and Rady Children’s Hospital, offering licensed therapists (both on campus)

- Recovery services, through Union of Pan Asian Communities (on campus)

- Laundry facilities, washing machines for student/family use (on campus)

- College and career services, through Avenues for Success (on campus)

The Union Role

San Diego Education Association is unique in that it won a contract fight with the school district in the 1990s that codified shared decision-making. This has proved crucial to San Diego community schools’ success — and is a sticking point for other locals who do not have such contract language. Without it, educators, as well as parents, students and community members, often struggle to be heard and participate as equals. Many locals are now organizing to ensure shared governance is codified, for community schools and for the public education structure that best serves students.

“SDEA has advocated for community schools because we view them as a way to elevate the voice of our highest-need school communities and get more resources and better processes to the students that we serve,” says SDEA President Kyle Weinberg.

CTA’s role is important on a statewide level. “CTA has been essential to establishing strong community schools in California — lobbying with the State Board of Education, with the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, to make sure that the pillars and mechanisms of transformative community schools are embedded into state policy,” Weinberg says.

CTA and Community Schools

CTA is deeply committed to helping grow and support California’s community schools, a partnership with the state, school districts, students, families and communities. Community schools’ democratic model of shared decision-making ensures all students’ needs are addressed so they can thrive and helps build power with community that leads toa more equitable society. Read more of our coverage of CTA and members’ work, and find information and resources, at cta.org/communityschools.

CTA is deeply committed to helping grow and support California’s community schools, a partnership with the state, school districts, students, families and communities. Community schools’ democratic model of shared decision-making ensures all students’ needs are addressed so they can thrive and helps build power with community that leads toa more equitable society. Read more of our coverage of CTA and members’ work, and find information and resources, at cta.org/communityschools.

Media Spotlight

CTA’s series of TV, radio and digital ads spotlighting community schools are in full swing during this back-to-school season. They focus on the importance of the shared leadership and decision-making governance model that gives voice to educators, students, parents and community members. Watch them at youtube.com/@CaliforniaTeachers.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment