Illustration by Daniel Baxter

“We’re reimagining schools,” says educator Ingrid Villeda. “It’s so much more than what happens in class.”

As the community school coordinator at 93rd Street Academy in South Central Los Angeles, Villeda works with students and families to support and connect them with the resources they need to learn and thrive. During the pandemic, her work has included delivering groceries to 250 school families every two weeks, the creation of a “giving room” with clothing, shoes and other items for students and families in need, and an after-school virtual enrichment program focusing on dance, art and sports.

“The community schools program is meant to support everything the students do,” says Villeda, a member of United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA). “They can’t focus on academics if they’re hungry or sad or tired.”

Ingrid Villeda, forefront, with colleagues helping distribute food at 93rd Street Academy in Los Angeles.

With massive investments by the state and federal government, community schools are getting historic resources at a time when students and families need the support most. The community schools model is aimed at disrupting poverty and addressing long-standing inequities, highlighting areas of need, and leveraging community resources so students are healthy, prepared for college and ready to succeed. A community school is both a place and a set of partnerships between the school and other community resources with an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, leadership, and community engagement, leading to improved student learning, stronger families and healthier communities.

Since each community school is centered around local needs and priorities, no two look exactly alike. But they all share a commitment to partnership and rethinking how best to provide the resources students and families need.

“Your school has needs. As a community school, you identify and elevate those needs,” says Nick Chandler, community school coordinator and United Educators of San Francisco (UESF) member. “It is our role to elevate and push until that need is met.”

CTA Vice President David Goldberg says supporting the community school movement is a priority for CTA, with significant implications for justice and democracy as schools and families examine whom schools serve and how decisions are made. The possibilities are exciting, he says.

“This is why I got into this movement and became a teacher — to make a true difference in a powerful way,” Goldberg says. “Community schools are a chance to do this.”

“This work means so much to me, because you have to build love, passion and commitment for your town and the people we serve. Community schools are a way to cultivate that.”

—Danielle Rasshan, Associated Pomona Teachers

The heart of the community

Danielle Rasshan had taught at Ganesha High School in Pomona for more than 20 years when the school was chosen to be part of the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) community schools pilot program in 2019. She was always “tied in” to which students needed more support and often intervened as the last stop to help some students before they faced serious discipline. Rasshan says she noticed the community school difference immediately, especially when it came to connecting students with resources and services.

“Now everything is located at my school. I know who to reach out to when I have a student who needs anything. I used to have trouble getting in touch with families, but now I can reach them through regular community workshops,” says Rasshan, a member of Associated Pomona Teachers. “Community schools empower parents because their health and success create the best environment for their students to succeed.”

Rasshan says having these relationships meant that when the pandemic struck, a network already existed to reach out to school community members to provide support. She says several food distributions were held at Ganesha High and its feeder schools (“We consider them part of our family, too”), while the school quickly distributed necessary technology and addressed connectivity issues. Ganesha also used COVID relief funds to hire more tutors when the pandemic forced in-person tutoring opportunities to go virtual.

“This work means so much to me, because you have to build love, passion and commitment for your town and the people we serve. Community schools are a way to cultivate that,” Rasshan says. “I think we’re going to see some real effective change.”

A community school should be the heart of a community, uniting diverse and engaged stakeholders to strengthen the school community and support the whole child — meaning students are not only supported in academics but also learning in environments that make them feel safe, valued, engaged, challenged and healthy.

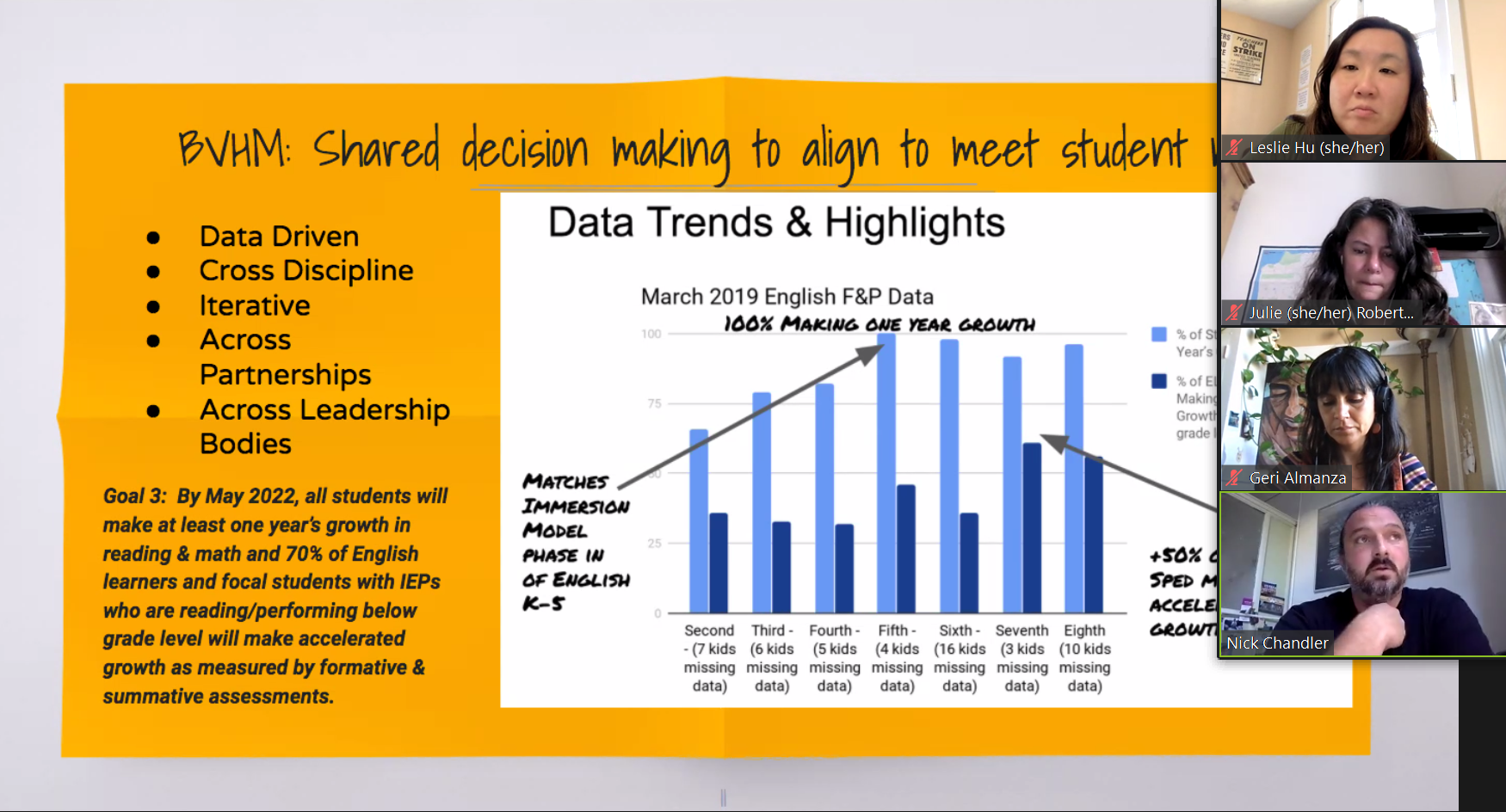

At Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School (BVHM) in San Francisco, families expressed a need for help with a safe and stable place to sleep at night. What followed was a deliberate and coordinated effort to elevate the issue, leading to the creation of the Stay Over Program, a cross-sector collaboration that provides an overnight sleeping program for up to 20 BVHM families in the school’s gymnasium — the only program of its kind nationwide.

Nick Chandler

“We started with the need, we started with the data, and then we moved forward with shared leadership,” says Chandler. “We have successfully hosted hundreds of families.”

In Los Angeles, 74th Street Gifted Magnet Community School Coordinator Nicole Douglass says the school became a community hub during the pandemic, with families turning to it for everything from groceries and school supplies to mental health services. Formerly a special education teacher there, Douglass continues to serve the school community, forging connections and helping families do more than just hold on.

One Friday at 5 p.m., a phone call came from a mother who needed food for the weekend, saying that being able to make her family a traditional Nigerian meal would mean everything during difficult times. Since items from food banks don’t typically include the necessary ingredients for such a meal, Douglass and her colleague pooled their money, delivering $50 to the mother so she could cook the food that would bring smiles to her family’s faces during difficult times.

“There are a lot of stories like that for us, and it’s brought us closer to our families when we needed to be. If the pandemic didn’t happen, I don’t think we would’ve been able to dig this deep,” says Douglass, a UTLA member. “We’ve been able to connect with our families and students on a deeper level, and it will be lifelong.”

“This is why I got into this movement and became a teacher — to make a true difference in a powerful way. Community schools are a chance to do this.”

—CTA Vice President David B. Goldberg

A movement born out of struggle

While community schools as a concept have been around since the turn of the century (thanks to famed social worker Jane Addams and educator John Dewey), the movement to create these centers of transformative change got a huge boost in 2019 when UTLA members included community schools in their demands during their historic strike. They won funding for 30 community schools and additional UTLA positions as part of Los Angeles Unified’s Community Schools Initiative. With California now investing more money into the community schools movement than all other states combined, Goldberg says, it’s important to remember the sacrifice educators made to win this funding for students and families.

“Part of the reason we can do this is because of the courageous efforts of our locals. It allows us to bring CTA support and infrastructure to these struggles that have been so powerful and meaningful,” Goldberg says. “What UTLA has done is the gold standard for community schools.”

CTA President E. Toby Boyd talks to a child at Prescott Elementary School in Oakland.

UTLA’s victory has blossomed into a $3 billion windfall for community schools — one-time Proposition 98 funding through 2028 to expand community schools across the state through the California Community Schools Partnership Program. School districts with more than 50 percent of students qualifying for free or reduced-priced lunch will be eligible for grants, with priority given to districts with greater need, those disproportionately impacted by COVID, and districts with a plan to sustain community school funding after the grant expires. Sustaining funding is a key piece to achieving the goal of turning every school where 80 percent or more of students live in poverty into a community school over the next five years.

On the federal side, President Biden’s budget includes $443 million for schools to become community schools, nearly 15 times the previous amount.

CTA has long been advocating for more funding for community schools. President E. Toby Boyd made a request to prioritize community schools as a member of Gov. Newsom’s state Task Force on Business and Jobs Recovery to provide more medical and mental health services to students amid the pandemic and as an integral part of an equitable restart to in-person learning.

“This investment in community schools is hugely important. When we talk about reimagining public education, community schools are a big part of that vision,” Boyd says. “It’s how we connect what’s best for students and educators to parents and our communities.”

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, shown visiting Ganesha High School in Pomona, says community school funding is “a dream come true.”

One prominent supporter of community schools first proposed funding the model when he was a school board member more than a decade ago. Now state superintendent of public instruction, Tony Thurmond says he is excited for the opportunity and grateful for the funding.

“It’s like a dream come true for the types of supports our students need. Given what we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, the timing couldn’t be better to make investments in community schools,” Thurmond says. “As a former social worker, I see community schools as the ultimate way to support whole child learning.”

Thurmond says the funding could result in one-third of all California public schools becoming community schools, and he’s eager to lay groundwork for supporting them past the one-time funds, including potentially leveraging federal funding for more mental health and medical services. He adds that the California Department of Education is planning to hold a series of listening sessions on the grant process before opening the application period, noting that CTA will be involved “in a significant way.”

Thurmond says he is eager to replicate the success of Los Angeles-area community schools in supporting the whole child and prioritizing equity.

“LACOE and LA Unified provide us with really rich examples of places we can learn from,” Thurmond says, adding that he’s excited to partner with educators in this important movement. “UTLA put it forward. I want to thank everyone in the CTA family for having the vision to call for community schools.”

“We are committed to improving the educational experience of our young people. Community schools provide the framework for how we do that.”

—Leslie Hu, United Educators of San Francisco

Support from CTA and NEA

In addition to state and federal funding, NEA and CTA are providing resources to support local associations to join the community schools movement. NEA is directing $3 million annually to help school districts make the transition to community schools, starting with the 100 largest school districts in the country.

CTA is creating a network to support local associations in community school initiatives. There are 20 CTA locals taking part in the NEA Strategic Campaign on Community Schools, with most receiving NEA Community Advocacy and Partnership Engagement (CAPE) grants to support their organizing efforts. Westminster Teachers Association (WTA) is using some of its $75,000 grant to build a partnership with the district’s parent-teacher association and start a conversation about community schools with families. WTA is also offering a stipend to a district parent to be a part of the community school leadership team and help promote and organize community schools in Westminster.

“I’m really happy that NEA is doing this,” says WTA President Kim Bui, noting how important it is to build a culture of collaboration with families. “We have each other and we support each other. We can do so much together for our community and our kids.”

Kim Bui

San Diego Education Association (SDEA) leaders parlayed an NEA training on building a community schools coalition four years ago into convincing the San Diego Unified school board to adopt a supportive resolution last year and develop a plan to open five community schools for the 2022-23 school year. SDEA, which is also a CAPE grant awardee, is working with school sites to prepare for the state grant application process, developing their community school pillars and strengthening partnerships, according to SDEA Vice President Kyle Weinberg.

“The funds from the grant are going into developing the leadership and coaching skills of our members who are doing this work,” he says. “NEA has done some groundbreaking work with community schools. It inspired us at SDEA to attempt to implement community schools with fidelity. We’ve taken a lot of the guidance from NEA and CTA to heart about what a community school can look like.”

Leslie Hu, community school coordinator at San Francisco Unified and UESF member, has been working with NEA and receiving coaching for the past few years to expand the community school movement nationwide. She says community schools are effective vehicles to uplift the voices of young people and families.

“It’s all based on what they need, on what the communities hope for,” says Hu. “We’re really interested in centering our young people and families. How do we use the power and resources of the union, of CTA and of NEA, to push this work forward?”

Mayra Alvarado

Mayra Alvarado teaches at Manzanita SEED Elementary School — one of more than 40 community schools in Oakland. She says educators and parents got a lot closer as they weathered the pandemic together, utilizing their “parent-teacher union” to organize and fight for the needs of their school.

“It’s about parents supporting teachers as workers, and teachers supporting parents in what they need for their children,” says Alvarado, an Oakland Education Association member. “Our teachers are aware of where our families are coming from. I wish I went to a school like the one I’m teaching at!”

For more information about CTA and NEA’s work on community schools, go to cta.org/communityschools.

United Educators of San Francisco is holding webinars to educate members about community schools and organize for funding.

Shared Leadership: Key to Success

A crucial piece of the community schools model (and one of the most difficult) is shared leadership. School leadership teams include educators, students, parents and community members. These teams share the responsibility of school operations with the principal, and they ensure the school is serving the needs of the school community.

“Shared leadership is a difficult thing because people traditionally in power have to give some of that up,” says Leslie Hu, community school coordinator and secretary of United Educators of San Francisco. “When you center schools around student and community voices, it makes it hard for a traditional approach.”

As one of the major pillars of community schools, inclusive leadership is a commitment to the school community that students, families and educators will be part of the decision-making, implementation and accountability process. This ensures that solutions are built with shared interest and responsibility.

“That’s really a game changer for our roles as educators,” says Kyle Weinberg, vice president of San Diego Education Association. “Governance of schools is not set up to be equitable. If you’re intentional about investing in collaborative leadership, it will pay dividends.”

For community school coordinator and United Teachers Los Angeles member Nicole Douglass, it’s just not possible to accomplish the goals of supporting students and uplifting communities without sharing goals, responsibilities and leadership.

“If this is a community school, there is no one leader,” she says. “Shared leadership is everything.”

A true test of family partnership at community schools, Hu says, is who the school considers to be experts on students and their needs.

“Do you think of the parents as experts, or do you center yourself as the expert? That’s a significant shift,” she says. “If we believe young people are the experts on their own lives, that families are experts on their own children, schools will look totally different.”

“We view it as an opportunity to empower all the stakeholders in our school communities. What’s transformative about community schools is the empowerment.”

—Kyle Weinberg, San Diego Education Association

Educators Request Parameters for Community School Funding

The state’s $3 billion investment is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and CTA leaders are focused on ensuring the historic funding is used to create the community schools that students and families need across the state.

Children at book and backpack giveaway at 93rd Street Academy in Los Angeles.

In a letter to Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond and State Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond, the presidents of the 20 CTA local associations participating in NEA’s Community Schools Strategic Campaign Institute requested the creation of a statewide Community Schools Steering Committee. This body would ensure democratic community stakeholder involvement, overall state-level ongoing guidance, community education and engagement, pathways to sustainable funding, and ongoing evaluation, assessment and support — essential to the success of community schools.

The CTA locals and their community partners also proposed regulations for school districts that receive state community schools funds, requiring:

- A rigorous and bottom-up application process to become a community school.

- Full-time community school coordinators at each school.

- Additional funding at each school annually to build the program.

- Training and systematic coaching for coordinators and others to support the leading and implementation of assessment of needs and development of a strategic plan at each school.

- Professional development, training and systematic coaching on culturally responsive curriculum, community organizing, and other key pieces of the community schools model.

- Expanded decision-making purview for parents, youth, community and educators at each community school.

- A Community Schools Steering Committee in each district that receives funding to guide the process with the above elements; help assess and evaluate the work; lead on broad community education about community schools; spearhead creating sustainable funding for community schools; and ensure broad and diverse community involvement and stakeholder leadership.

Money for Community Schools

Tony Thurmond, state superintendent of public instruction, says the increase in funding could result in one-third of California’s 10,600 public schools becoming community schools.

- $3 billion from the state: One-time Proposition 98 funding through 2028 to expand community schools across the state through the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP). The goal is to transition every school where 80 percent or more of students live in poverty into a community school over the next five years. School districts with more than 50 percent of students qualifying for free or reduced-priced lunch will be eligible for grants, with priority given to districts with greater need, those disproportionately impacted by COVID, and districts with a plan to sustain community school funding after the grant expires. Thurmond will present the CCSPP plan to the State Board of Education for approval in November.

- $443 million from the federal government: Funding in President Biden’s budget for U.S. schools to become community schools, nearly 15 times the previous amount.

- $3 million from NEA: Annual funding to help school districts make the transition to community schools, starting with the 100 largest school districts in the country. Twenty CTA locals are taking part in the NEA Strategic Campaign on Community Schools, with most receiving NEA Community Advocacy and Partnership Engagement (CAPE) grants to support their organizing efforts. Details about CAPE at nea.org/cape.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment