“IT ’S EXCITING and invigorating to do this work,” says Elizabeth Kocharian, a Bell Gardens High School teacher on partial-release time working as a community schools coordinator for Montebello Teachers Association. “We all know the challenges our families are facing but now we have the opportunity to help them.”

The movement to build transformative community schools continues to grow in districts throughout California, thanks to resources from the state’s landmark $4.1 billion investment and the efforts of educators and their local associations. With the first round of planning and implementation grants awarded in May 2022, school districts are developing and enacting plans to build community schools that support the identified needs of their students and community.

During this first round of grants, local associations are generally encountering three distinct reactions from school districts: interested and willing to plan collaboratively with educators and stakeholders; interested but unwilling to work collaboratively; or uninformed and/or reluctant to apply. While each of these require a different response from locals in working toward the inclusive and collaborative planning needed to build community schools, the end goal is the negotiation of an agreement with the district outlining the shared governance structure for each community school.

A strong partnership between educators, parents, community and the school district are all vital pieces to a successful community school, but the lack of a collaborative relationship with district management doesn’t mean the community school effort grinds to a halt. Local associations are organizing in their communities, building relationships with parents, neighborhood groups and other organizations, and continuing necessary work to build community schools.

CTA and NEA have been at the forefront of efforts to build community schools, providing resources and guidance to educators and local associations as they embark on this important work. And now, CTA leaders and staff have developed a five-step path to help locals build member and community support.

Here are the steps to building successful community schools, as illustrated through the journeys of five local associations.

Step 1: Build Chapter Leader Support

Step 1: Build Chapter Leader Support

When FSUTA President Nancy Dunn first heard about community schools, it sounded a lot like the work Fairfield-Suisun educators were doing to build relationships in their community and capacity in their local. FSUTA applied and was selected for NEA’s community schools cohort in 2021, also receiving a $75,000 NEA grant. Dunn says that the district’s superintendent is not interested in collaborative leadership, so FSUTA is focusing on building internal capacity, identifying new leaders, and developing partnerships to be ready when that changes.

Nancy Dunn

Dunn says that community schools are a part of FSUTA’s organizing plan, which she and Organizing Chair Audrey Jacques presented to both their executive board and representative council to build support among FSUTA leaders.

“Part of it is the commitment to writing it down and being able to go back to our policy-making bodies to say ‘we committed to doing this,’” says Dunn.

FSUTA used the grant funds to release Jacques from the classroom to work full-time starting last February on organizing and community schools — engaging new members, building relationships and taking note of potential leaders.

Audrey Jacques

“We’ve been able to identify a lot of members who were looking for something that spoke to them,” says Jacques, explaining that FSUTA established four new caucuses to provide spaces for members to meet and share. “We’re building relationships with community partners, but we needed to build relationships among our members as well.”

Dunn says FSUTA made changes to their structure to enhance member voice in the local and share leadership responsibilities among more members. Jacques is building action teams at school sites, creating new links between educators and their union, and developing collaborative leadership in FSUTA as a model for when they have district leadership willing to work together to support students and their families.

“We’re hitting all of the notes, so when the ability to collaborate becomes available, we’re ready to go,” says Dunn. “We have all the pieces in place other than the district.”

Step 2: Build Educator and Student Support

NTA’s advocacy for community schools in the early stages of Natomas Unified’s planning grant application led to strong foundations for building a collaborative process. President Mara Harvey says the local continues to share resources with district administrators to ensure effective implementation, including development of shared leadership structures. NTA is focusing on working with members at the district’s selected community school site and districtwide to help foster understanding about the potential impact of community schools.

Mara Harvey

“We’re working to ensure educators and parents have voices in schools. That’s an exciting idea for educators,” says Harvey. “There’s this huge well of opportunities for our students. A lot of people are excited to get the resources to our families.”

Harvey says they are currently analyzing community needs at their future community school site to determine what supports are necessary when it opens next school year. That information will be used to help identify potential needs in other schools.

“The more resources we can get to our students, the better,” Harvey says. “It’s exciting to me because education is about bringing your community together.” Harvey says talks are ongoing between NTA and Natomas Unified to reach a memorandum of understanding about shared governance.

“How do we guarantee a role in leadership in this effort? We see it as fundamental to the success of community schools. That is really the key piece,” she says. “We want to have a collaborative relationship. It’s about setting up a structure, so everyone has a voice.”

Harvey says it has been helpful to have a neighboring local — Twin Rivers United Educators — that is a couple years ahead on the community schools timeline and willing to provide advice and support as needed. For local associations just starting, she recommends reaching out to fellow CTA leaders building community schools in their districts.

“What are other districts doing and how can that work for us,” Harvey asks, adding that CTA support has been invaluable. “CTA has been really strong behind us and there’s so much excitement about it.”

Step 3: Build Parent and Community Support

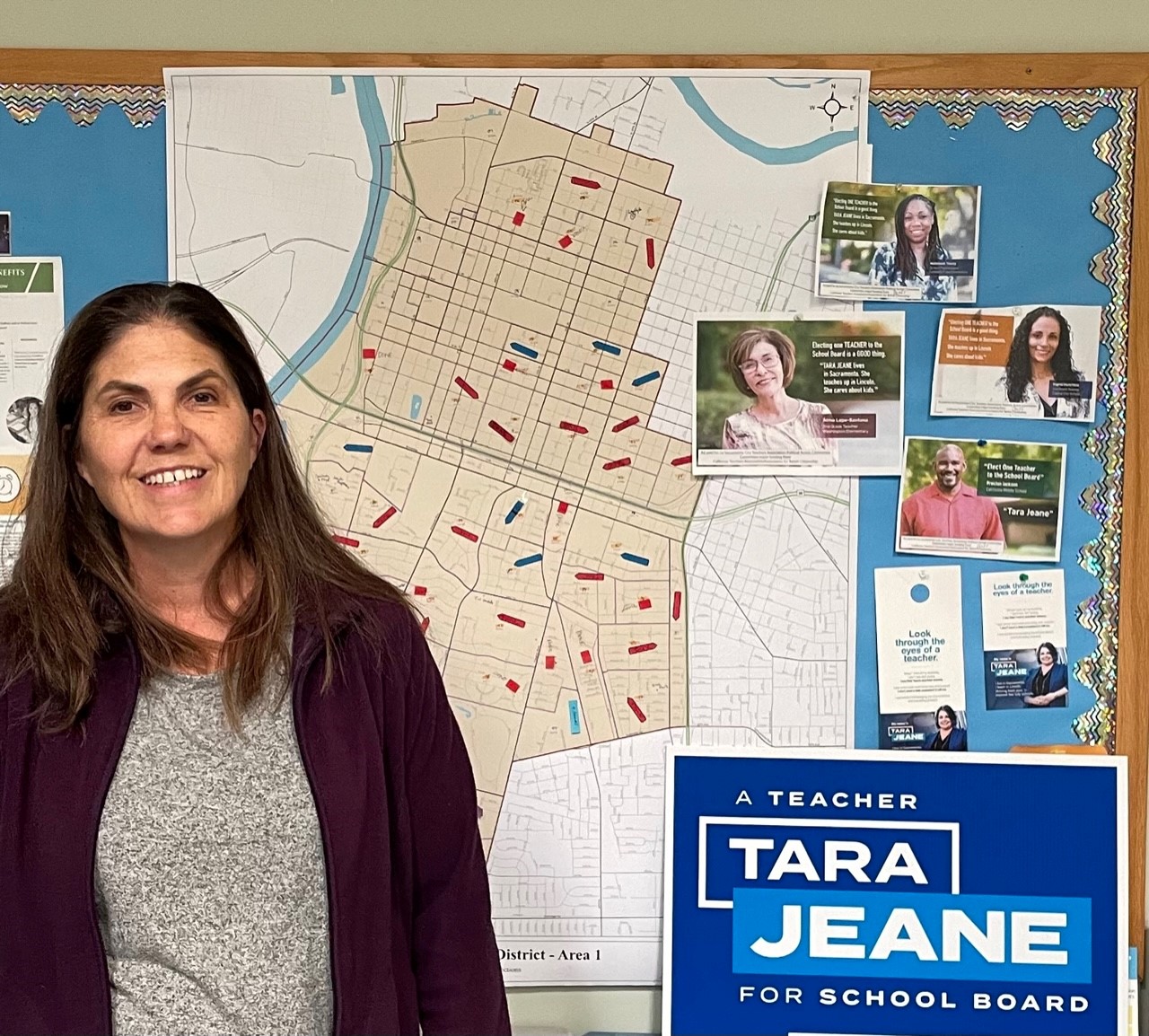

Sac City TA made a community schools proposal that the school district refused to even discuss during bargaining leading up to their strike last March, but that hasn’t stopped educators from moving forward with plans to build community schools in Sacramento. This includes successful action at the ballot box in the November 2022 election.

Sac City TA made a community schools proposal that the school district refused to even discuss during bargaining leading up to their strike last March, but that hasn’t stopped educators from moving forward with plans to build community schools in Sacramento. This includes successful action at the ballot box in the November 2022 election.

“Community schools fit very tightly with priorities we set in 2016 and build an avenue for things we want to accomplish for our students,” SCTA Vice President Nikki Milevsky says.

During their strike, three parents led more than 50 parents, students and community members in occupying the school district office and demanding to speak to the superintendent, signifying the community’s solidarity with educators and helping lead to Sac City TA’s settlement victory that ended the eight-day strike. SCTA hired one of those parents to work as a community schools organizer and help build relationships.

Nikki Milevsky and SCTA ran a school board campaign last year to elect leaders who would direct district management to collaborate with educators and the community on, among other issues, community schools. Three SCTA-supported candidates won, flipping the board and changing the direction of the district.

“She’s been doing a great job organizing parents and school site councils for community schools,” Milevsky says. “It’s just amazing how similar educators’ thoughts are to parents’ and the community’s thoughts. The goal is the success of our students.”

Knowing that they would make no progress on community schools as long as their superintendent lacked the desire to work with them, SCTA set out on an ambitious school board campaign last year to elect leaders who would direct district management to collaborate with educators and the community. SCTA mounted an extensive community-based campaign, supporting a CTA educator and two community

members who emerged during the strike as community leaders. In a massive victory, all three won election, flipping the school board and changing the direction of the district.

“That’s been a critical step in moving forward for community schools,” Milevsky says. “The teachers and community are going to fight to get true community schools for our students.”

Milevsky recommends working with community and parent groups to learn about their needs and wishes for their students. She says it was inspiring to hear from other locals and working community school coordinators at last year’s Summer Institute and learn from their experiences.

“We’ve found CTA and NEA support to be invaluable in this effort,” Milevsky says. “It’s so powerful to know you’re not alone.”

Step 4: Plan Collaboratively with the District

Montebello educators are planning for community

Montebello educators are planning for community

schools on the ground and at the bargaining table, with MTA making a community schools contract proposal late last year that outlines structures for shared leadership. MTA reached a tentative agreement in January on a new community schools article in their contract, which establishes a joint steering committee that will make recommendations regarding the implementation of the community schools program, including applying for an implementation grant from the state. While the grant would provide necessary resources, President David Navar says MTA educators are ready to build community schools in Montebello, regardless of the outcome.

David Navar

“We want community schools in our district whether we get the grant or not,” Navar says.

In 2021, MTA received a $75,000 grant from NEA for community schools planning, which they used to organize internally and release a teacher full-time to work on community schools (see sidebar). MTA held a community schools public forum and a series of trainings on leadership development, inviting educators, parents and community organizations to participate. Navar says these sessions were wildly popular and important in building their movement.

“We need to be ready from an organizational perspective to demand and win community schools,” he says. “The school board knows that MTA is leading the charge for community schools. It is in the minds of people that this is the focus of our association.”

MTA adopted an educational justice resolution in 2021, which Navar says aligns with the goals of community schools. MTA is currently building capacity for the community schools effort, which includes educating members and the community about the power of these spaces. He’s also hoping that district management will better embrace community schools — their responses have been tepid at times and collaboration lacking, according to Navar.

The groundwork continues to build community schools in Montebello, where Navar notes the amount of work they’ve done organizing and planning without yet having one (Note: There is a community school in Montebello, but it is funded by Los Angeles County Office of Education). He can’t wait until these efforts come to fruition.

“Our students are who this was made for,” Navar says.

Step 5: Build Structures for Shared Decision-Making

Things are moving fast in Vista Unified, where the district is in the process of implementing five community schools. VTA President Keri Avila says schools at the district had already been providing wraparound services to students and families, so the community school model was a natural fit.

Things are moving fast in Vista Unified, where the district is in the process of implementing five community schools. VTA President Keri Avila says schools at the district had already been providing wraparound services to students and families, so the community school model was a natural fit.

“It’s an aggressive plan, so we’re implementing while we’re figuring it out,” Avila says.

The district’s community schools steering committee includes VTA educators, but not education support professionals, parents or community — so Avila says VTA worked to ensure those voices are on site-level committees. Each of the district’s community schools will have a community school coordinator, family liaison, school counselor and an additional full-time position, which Avila says could potentially be used to focus on personalized instruction.

Keri Avila

With things moving quickly, Avila met with educators at the soon-to-be community schools to discuss the model and answer questions. VTA accepted an invitation from Anaheim Secondary Teachers Association to visit a community school there, bringing along educators, the district’s community schools coordinator and a parent — who has become a staunch advocate for the same transformative experiences in Vista. Now, VTA and the district are building shared leadership structures.

“It really brought it home to see how Anaheim was doing shared leadership,” Avila says. “It made us think about how we can build community schools like this in Vista and how can we get people to support them?”

Avila is working with the school board to craft a community schools resolution. She says it’s an ongoing effort to get management to share power, noting that “being a part of the conversation is a good place to start.” When VTA hit roadblocks with district-level management, Avila says they transitioned to working with school site administrators to share information and collaborate on community schools, building their local movement together.

“We could do a demand-to-bargain for all these things, but if we are working together on shared leadership, then that’s not necessary,” she says. “We’re making sure the boxes aren’t just being checked, and the collaboration is authentic and real.”

Educator on Full Release for Community Schools

Elizabeth Kocharian

Elizabeth Kocharian became fully immersed in the community schools movement last October, transitioning from teaching governance structures to Bell Gardens High School students to organizing and building them as a community schools coordinator for Montebello Teachers Association.

The 20-year history and government educator was on full and is currently on partial release time from the classroom, building relationships between educators and parents, community groups and the school district. Kocharian works closely with fellow teachers to create workshops and sessions to develop the foundational knowledge necessary to create transformative experiences for Montebello students. She’s excited to work to build community schools in her hometown.

“We know our students and our families. We know what we need. And this is our opportunity to create schools where every student gets what they need to succeed every day,” Kocharian says. “Being on release is really important — this isn’t something you can do well if you’re working in the classroom.”

Kocharian is getting help and support from fellow educators. She attended the community schools strand at last year’s Summer Institute, meeting members doing similar work from locals including Chula Vista Educators and United Educators of San Francisco, and joining a Slack channel set up by them to share information about community schools and their efforts.

Kocharian says MTA’s adoption of an educational justice resolution in 2021 was the impetus to go further and learn more about community schools.

“It really expanded my view of what a community school can be, and the possibilities are limitless. We don’t have to model our school like anyone else,” Kocharian says. “How do we create educational justice and what does that even look like for our students?”

Looking ahead, Kocharian is hoping that one to three Montebello schools apply to be community schools by June, as they continue to develop the structures for shared leadership.

“MTA is building a model for how to meet every student’s needs and engage the entire family in collaborative leadership,” she says. “I want this to be sustainable, and that’s the only way we can guarantee it will continue.”

What is a Community School?

A community school is both a place and a set of partnerships between the school and other community resources with an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, leadership and community engagement, leading to improved student learning, stronger families and healthier communities. Community schools are collaborative efforts, where school district administrators share decision-making power with educators, parents and community groups to provide the support students and families need every day. Visit cta.org/communityschools for more information and previous coverage.

For all CTA videos on community schools, including roundtable discussions with educators, interviews with CTA and state leaders, and more, go to our playlist at bit.ly/3HMkmcc.

Check out our story on Anaheim Secondary Teachers Association (ASTA) and the work its leaders and members are doing around community schools in Anaheim Union High School District, next page. And view a new video about the effort, with input from ASTA educators, students, school and district administrators and State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, at bit.ly/3R7Hmpe.

Second Round of Grant Funding Underway

California has invested $4.1 billion to support and expand community schools through the California Community Schools Partnership Program. Funding is through grants from the California Department of Education.

A second round of grant funding is now underway: The application period for implementation grants — grants for those districts and Local Education Agencies with an existing community schools program — will close March 17, 2023. Implementation grants are funding for up to five years for up to $500,000, depending on school enrollment. For details on CDE grants for community schools, go to

cde.ca.gov/ci/gs/hs/ccspp.asp.

Community Schools Event at CAAASA March 17

CTA Vice President David Goldberg

A special panel discussion will take place at the California Association of African-American Superintendents & Administrators’ annual summit on Fri., March 17: “Community Schools: The Roadmap to Academic Success for African American and Other Students of Color.” CTA Vice President David Goldberg is one of the featured speakers.

The theme of the summit, at Hyatt Regency Orange County, is “Building a Powerful Equity-Centered Education.” Attendees can register for virtual or in-person attendance. For details, visit caaasa.org/2023summit.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment