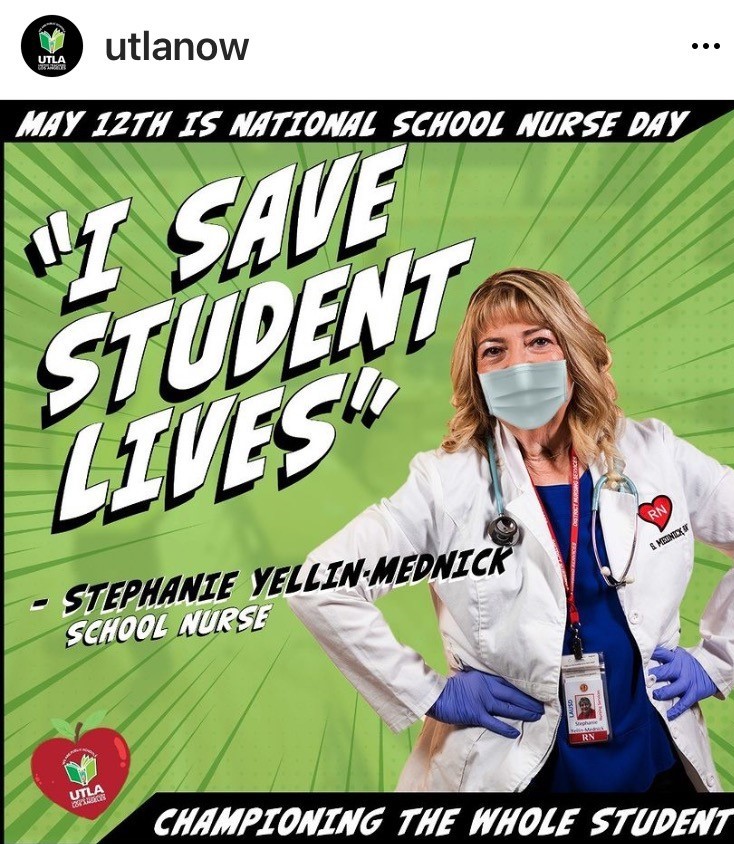

Our 2021-22 Innovation Issue salutes educators who dare to imagine a world where life is better for their students:

“Not all superheroes wear capes; some of them wear scrubs. This has definitely been the year of the school nurse.”

When LA students returned to school in August and some tested positive for COVID-19, an administrator turned to school nurse Stephanie Yellin-Mednick and asked, “How do we handle this?”

She instantly knew that she and other school nurses — already overworked and stretched thin — would need to assume leadership roles in the pandemic and work in new and groundbreaking ways.

Yellin-Mednick is a nurse at Sherman Oaks Center for Enriched Studies, a magnet school for more than 1,900 students in grades 4-12 that is part of Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). She is also lead chair for the nursing chapter of United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), which has more than 500 nurses.

The question “How do we handle this?” was sobering, she recalls. She knew she would have to oversee school safety measures to prevent COVID from spreading, and also be a strong advocate for the safety of nurses and health care staff through negotiations at the bargaining table. Both roles meant venturing into uncharted territory, but she did it.

“You step up to the plate and put on your big girl pants and realize that you are the medical person and expert on campus that others are looking to for answers. Nurses may have never done these things before, but we have trained for this.”

Like other district nurses, she conducts COVID rapid tests of students returning from quarantine and also tests those who have failed to get the “daily pass” required of all students, who must log into their account and answer questions about COVID symptoms each morning.

Yellin-Mednick checking a COVID-19 rapid test.

She helps with contact tracing, analyzing seating charts and lunch tables to see which students and staff have been exposed to someone who has tested positive. She calls the parents of students who have tested positive or been exposed, and oversees “isolation areas” where students who test positive wait for their parents.

And because school nurses can only be in one place at one time, she helped train office staff and school aides to step in as needed, doing things like taking temperatures and observing symptoms. She also trained teachers how to properly sanitize classrooms in between different groups of students.

When vaccines came out, she helped administer vaccinations to district staff.

All these new responsibilities are in addition to her existing duties of caring for students with special needs, who may require assistance with feeding tubes, catheters, insulin injections or asthma attacks, as well as monitoring students’ immunization records and treating injuries.

“It’s been said that not all superheroes wear capes; some of them wear scrubs,” says Yellin-Mednick, who has been a school nurse for nearly 40 years. “This has definitely been the year of the school nurse.”

In her role as UTLA representative for nurses and health and human services staff (including mental health workers, psychiatric social workers, and pupil services and attendance staff), she helped negotiate a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for safer working conditions. The district had proposed that health care workers wear surgical masks and plastic aprons like cafeteria staff, which she viewed as unacceptable.

“If our people are going to be around those who are sneezing and coughing out the virus, I wanted us to be protected, just like nurses in hospitals. And that includes having scrubs and N95 masks, which we were able to receive through negotiations.”

The MOU ensured that staff who test positive or need to be quarantined can stay home without having that time deducted from sick leave. The same applies to those caring for relatives with COVID.

“I was part of the discussion about ventilation in the classrooms and the need for air filters to be changed. And when teachers negotiated their separate agreement, they pulled many of the things that we had already successfully negotiated with our district.”

Yellin-Mednick knew from age 5 she wanted to be a nurse. She made paper nurses’ hats for her dolls. Her parents hid the Band-Aids because she pasted them all over her friends. She called her little red wagon her “ambulance.”

She received a bachelor’s degree in health and safety and another in nursing, as well as a master’s in nursing administration, at CSU Los Angeles. She previously taught in National University’s school nurse credential program.

The pandemic is hardly her first challenging assignment. She was at 49th Street Elementary School in LAUSD during a mass shooting in 1984 when one child and one staff member died and 12 were wounded, and administered first aid to the wounded.

But Yellin-Mednick loves what she does because she knows that she is making a difference in the lives of students and their families.

“The job of a school nurse is to ensure that children are healthy, safe, and in their seats ready to learn. We are not paid enough for what we do. But as the pandemic has clearly shown, school nurses are an essential part of every school district.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment