“I’VE HEARD OF many teachers and even some students getting sick. They’ve had to close classrooms down for being unsafe,” says Sam Cleare, United Teachers of Richmond (UTR) organizing committee chair. “Students have gotten nosebleeds from the heat. Teachers have fainted. It’s unsafe.”

Sam Cleare

Across California, public school facilities are in dire need of maintenance and modernization, impacting teaching and learning conditions and putting students and communities in danger. The average age of our state’s more than 10,000 public schools is about 50 years old, with 38% of California children attending schools that don’t meet minimum standards — where they are exposed to dangers like asbestos, mold, unsafe drinking water and extreme heat. Union educators are organizing in communities statewide to defend their students and themselves and demand safe and healthy schools and classrooms.

At Stege Elementary School in Richmond, parents and the community tried to get dangerous conditions addressed for years when UTR members started organizing around the issue last year. Educators recorded a long list of hazardous conditions — mold in classrooms, broken ceiling tiles, inadequate climate control, lack of access to clean drinking water and windows in classrooms that don’t open, subjecting educators and students to temperatures exceeding 90 degrees — and filed complaints using the state’s Williams Act process, used to ensure districts provide basic safe and healthy conditions at all public schools.

“We collected almost 45 complaints from teachers, staff members, community and families — even some students wrote letters to the school board,” says Cleare, who taught at Stege for seven years. “We were strategic in using community events to engage in conversations. My

school had a movie night and members of our school leadership, teachers and other staff members were able to talk about the Williams Act and collect complaints.”

Black mold inside classrooms in Richmond (left) led to one school’s temporary closure, while lead rendered water undrinkable in some Oakland public schools.

West Contra Costa Unified School District admin failed to respond to UTR’s Williams complaints within the timeline required by law. UTR members began speaking at school board meetings about the hazardous conditions at Stege, attracting the attention of public interest legal group Public Advocates. Public Advocates reached out to UTR leaders to help with the issue, eventually filing a lawsuit against the district for failing to provide safe conditions for students.

While a judge dismissed the lawsuit, district admin finally sent investigators to Stege over the summer, finding asbestos and other unsafe conditions. Officials abruptly closed the school and temporarily moved all students and staff to a nearby campus, where similar conditions and issues exist, including a lack of access to drinking water for students. UTR leaders and its legal team are currently considering their next moves as the fight continues for the safe and healthy conditions Richmond students deserve.

“We’re definitely not done, and I feel like what we do next could create precedent in the state,” says Cleare, noting that UTR leaders have visited more than 50 district schools to survey conditions. “Unsafe facilities are impacting our students. Many schools have classrooms where temperatures regularly reach the upper 80s and play areas without shade. Something has to change — it’s absolutely unacceptable and illegal.”

Fighting for Lead-Free Water in Oakland Schools

“This speaks to decades of disinvestment in public education. We’re seeing a very tangible example of this disinvestment, which is the literal poisoning of our students and staff,” says Ella Every-Wortman, eighth grade teacher and Oakland Education Association (OEA) site representative. “Our students deserve schools that are safe and racially just.”

“I don’t want to be drinking lead. I don’t want lead anywhere near me. I want to be safe; I want to grow up safe.” —Hannah Lau, 13-year-old Oakland student, in an EdSource story about lead in the drinking water at public schools in Oakland

On the first day of school this year at Frick United Academy of Language in Oakland, district officials learned that six water fountains used by students had unsafe levels of lead in the water, prompting the principal to bag all the school’s drinking fountains. An eighth grade English teacher at Frick, Every-Wortman says that while this happened in August, the measurements were taken in April, which means that students were exposed to hazardous levels of lead for far longer than necessary.

Ella Every-Wortman

Every-Wortman, who uses they/them pronouns, says Oakland Unified administrators stepped up testing after OEA pushed for more attention to the matter, with upward of 40 schools testing positive for lead in drinking water — nearly half of the public schools in Oakland. OEA members learned that numerous sites districtwide experienced delays in reporting similar to Frick — meaning that widespread numbers of Oakland public school students were likely exposed to the toxic heavy metal.

“We discovered that they didn’t test every water source, so what about the safety of the sources they didn’t test?” they ask. “They’re still not taking this issue seriously when it’s obviously got potential impacts on the health of our students and staff.”

Like many schools in urban East San Francisco Bay communities, Oakland has a substantial number of older school facilities that have not been modernized to ensure safety for students and educators. The older pipes and valves have lead soldering, which can leach the hazardous metal into the water as they age. OEA continues organizing in school communities and advocating at school board meetings. The district has a plan, but Every-Wortman says it’s not fast or proactive enough to ensure student safety, with recently installed water filtration systems proving inadequate for the heavy daily use by hundreds of thirsty students at each school. OEA joined a coalition focused on the issue, Get the Lead Out of Oakland, issuing a list of demands to the district including lowering the acceptable amount of lead in drinking water to zero parts per billion.

“We had some very proactive teachers who were really speaking to the fact that the safest thing right now is to shut off the water sources and wait until we are sure everything is safe,” they say. “It’s well researched that there’s no safe level of lead in the water, especially when we’re talking about children.”

OEA has filed a grievance on the issue, is considering filing complaints with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and is examining how to address the safety and health issues in bargaining, though they say a short-term solution is needed now. But with an estimated $60 million cost to modernize all the unsafe schools, Every-Wortman says it’s not reasonable for Oakland Unified to have to fix the problem on its own.

“We need more funding and on a state level. We need to push toward a more unified vision of what the standard in public education should be,” they say. “We need safe drinking water, and anything that gets us closer to that is what we need to do.”

Auburn Teachers Battle District Admin for Safe Water

“Issues like this bring to light that we need to have more in our contracts about climate control and access to water,” says Sara Liebert, president of Auburn Union Teachers Association (AUTA). “We actually have to write this in our collective bargaining agreements now and hold our districts accountable because there are a lot of things that are not being taken care of in our schools.”

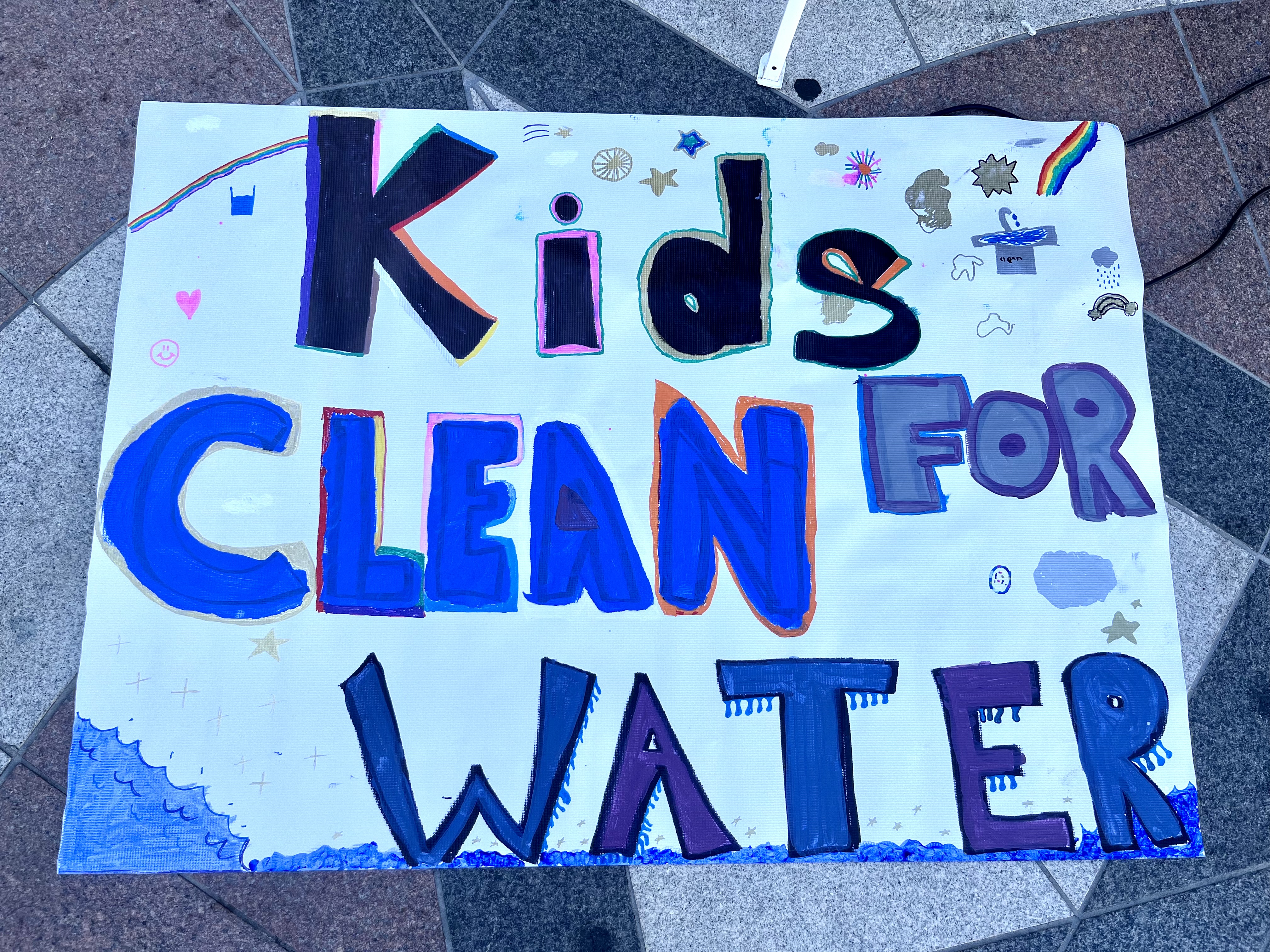

Led by president Sara Liebert (front row, third from left), Auburn educators fought the district to get safe drinking water for students.

Auburn teachers found themselves fighting for safe drinking water in the heart of Gold Country last year, when lead fixtures contaminated water in classrooms and drinking fountains. The district discovered the lead contamination in schools at the end of the previous school year and made necessary repairs at some sites with a promise to complete the others over summer. Liebert says that didn’t happen.

“It was a known fact that this was an issue, and it was supposed to be dealt with before the next school year,” the third grade teacher says. “When we started school, the sinks were roped off and there were signs that said ‘do not use.’ It’s Auburn and it gets really hot, so what are we supposed to do with our students?”

At first, district admin wasn’t providing safe drinking water for students, despite telling the community they were. AUTA started an information campaign in the school community to spread the word to parents and families and rallying to demand action.

“I talked to the superintendent and I wasn’t getting anywhere, so we went to the community to let them know their students didn’t have access to safe drinking water,” Liebert says. “It was a lot of education for our community, starting Facebook pages, making and posting videos, having our members be present, and holding up signs in both English and Spanish saying that we deserve access to clean water.”

AUTA also reached out to local media outlets, which spread the story and helped shine a light on the hazardous conditions in Auburn schools. This made for heated school board meetings, where school board members made personal attacks on Liebert and district admin made ridiculous comments, like when they claimed teachers were refusing deliveries of bottled water to the school (there was actually nowhere to store the massive pallets of water the district kept sending).

“We did a lot of picketing, made a lot of signs and organized parents and the community,” says Liebert. “After the media got involved, I think the school board felt a lot of pressure about our kids not having access to clean drinking water. Then parents started coming to the meetings and asking questions.”

The lead fixtures were finally replaced in November/December 2023 but that wasn’t the end of the ordeal — the pipes needed to be flushed for 45 days to ensure all the lead was gone from the system. This meant the water was unsafe to drink until early January, due to prolonged inaction from Auburn Union’s school board and administration.

Liebert says it’s important to lean into CTA resources and support when fighting for issues like this. While AUTA members organized on the ground, she said day-to-day support from CTA staff was invaluable.

“It’s that village,” she says. “Yeah, I’m the head of the local, but I have a huge village that’s willing to support us and we wouldn’t be successful without that. It was a team effort.”

Santa Maria Educators Plan Ahead After Power Outages

“I didn’t know the toilets couldn’t flush without power, until I needed to and there was no power,” says Riccardo Magni, a member of Santa Maria Joint Union High School District Faculty Association (SMJUHSDFA).

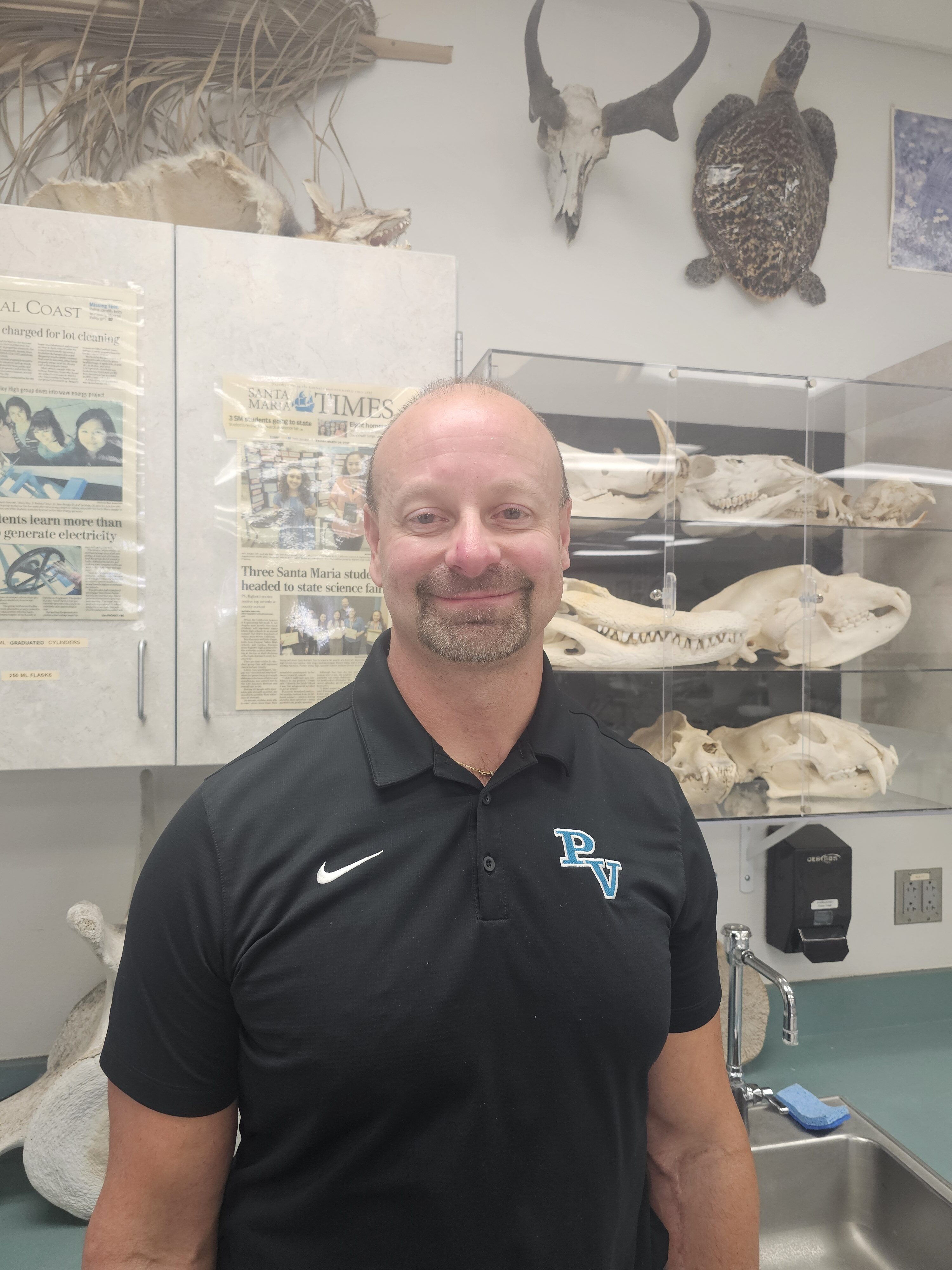

Riccardo Magni

Organizing to fight for student safety also means being prepared for the unexpected, whether it’s wildfires, unhealthy air, bad weather or power outages. SMJUHSDFA members found themselves dealing with the latter three times in quick succession this year, which spurred the local association to organize around preparedness and force the district to improve its systems.

“We have had in a six-week span all of our comprehensive high schools suffering a debilitating loss of electricity,” says Curt Greeley, president of SMJUHSDFA. “A car hit and took out a power line for one, there was an unexplained PG&E outage for another, and a third lost power when a power line broke. You can’t predict any of that.”

Greeley says educators learned quickly just how electricity-reliant their schools are when the outages killed all communications — no email, telephones, loudspeakers, even the bells. In one of the events, cell phone service also went down (and Greeley says it’s often spotty in some schools anyway), creating a potentially dangerous situation.

“It just really showed us that there were gaps in our technology, and we have to have contingency plans to address them,” says Greeley. “We’re currently working with the district to shore up those gaps.”

Curt Greeley

At another school, Greeley says they learned during the blackout that the toilets there also ran on electricity, discovering the batteries intended as backups in the event of an outage were dead. This meant there were 10 working toilets for approximately 3,400 people for more than two hours. Windows at the school are also fixed-closed, and temperatures became sweltering quickly without electric-powered climate control systems.

Magni said the situation was troubling for educators, who had no way of knowing what was happening and no way to contact anyone to find out.

“It was particularly frightening when the phones didn’t work,” says Magni, a science teacher and coach. “Since I have a door to the outside, I would open it and talk to the security guards to find out what was going on. Our administrators were not prepared for this, so it was really unorganized.”

SMJUHSDFA members have taken these experiences and used them to power an organizing campaign to fight for safe and healthy conditions for all. Greeley says they are meeting with district safety committees to share their voices and create the best teaching and learning environment in Santa Maria schools and ensure there’s a well-thought plan in the event of emergency situations.

“We have members who are passionate and knowledgeable and if we could have some inclusive leadership and more perspective on this, we can reach a better answer. This should be a district-led initiative across campuses so that teachers and staff have expectations,” he says. “We’d like to collaborate on what’s best for teachers, students and staff.”

Greeley’s message for CTA local unions fighting for similar health and safety improvements: You are not alone and remember that safety is the foundation for all supportive teaching and learning environments.

“Too often, we get caught up in teaching, learning, assessment and negotiating contracts. Our experiences this year have reminded us what the true mission of our union is — to keep our members safe when our employer can’t or won’t.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment