In July, Erika Martinez resigned from her teaching position at Liberty Elementary School in Tulare. With her school on the verge of resuming in-person instruction, Martinez quit her job to protect her 3-year-old daughter, parents and herself during a pandemic. It was an agonizing decision.

Erika Martinez with her 3-year-old daughter

Martinez has multiple sclerosis, and was worried that COVID-19 would worsen her condition. She also feared that her daughter could become ill or become a COVID carrier and infect her parents, who provided day care.

She thought about requesting a leave of absence. But for the good of her second graders, she decided to resign, because she feared that otherwise they might have a revolving door of substitute teachers. It was the ultimate sacrifice for this 13-year classroom teacher, who served as president of the Liberty Teachers Association.

Pandemic pushes women out of the workforce

Martinez is part of a growing wave of females being forced out of the workforce due to COVID-19, as women shoulder the responsibility of family and child rearing — especially during a time of sickness and economic upheaval.

While the surging virus has taken a toll on the overall job market — the Labor Department reported in December the loss of 140,000 non-farming jobs, a monthly job loss for the first time since April — women are bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s impact. That’s because they are disproportionately employed in the service and health care industries, which have been hit the hardest, in addition to having family obligations.

“I want to be a role model for my daughter and show her a woman can succeed as much as a man. But being a woman is hard. We have to juggle it all. And the pandemic is stretching us very, very thin.” – Erika Martinez, former president, Liberty Teachers Association

Four times as many women as men dropped out of the labor force in September — roughly 865,000 women compared with 216,000 men — mostly due to the need for child care, according to a Center for American Progress report, “How COVID-19 Sent Women’s Workforce Progress Backward.”

With schools and day care facilities closed in the pandemic, someone has to stay home with children and oversee distance learning. The lower-salaried spouse, usually the woman due to gender inequity in the workplace, typically fills that role.

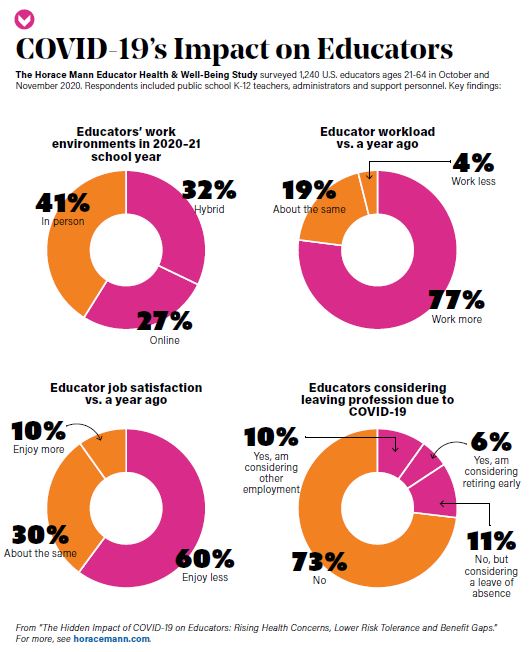

According to “The Hidden Impact of COVID-19 on Educators,” a report by Horace Mann published in December, 27 percent of teachers are considering quitting — at least temporarily — because of COVID. This mirrors a 2020 study by the Lean In organization, which found a quarter of women working in corporate America are considering “downshifting” their careers or leaving their jobs because of the pandemic.

Some are cutting back

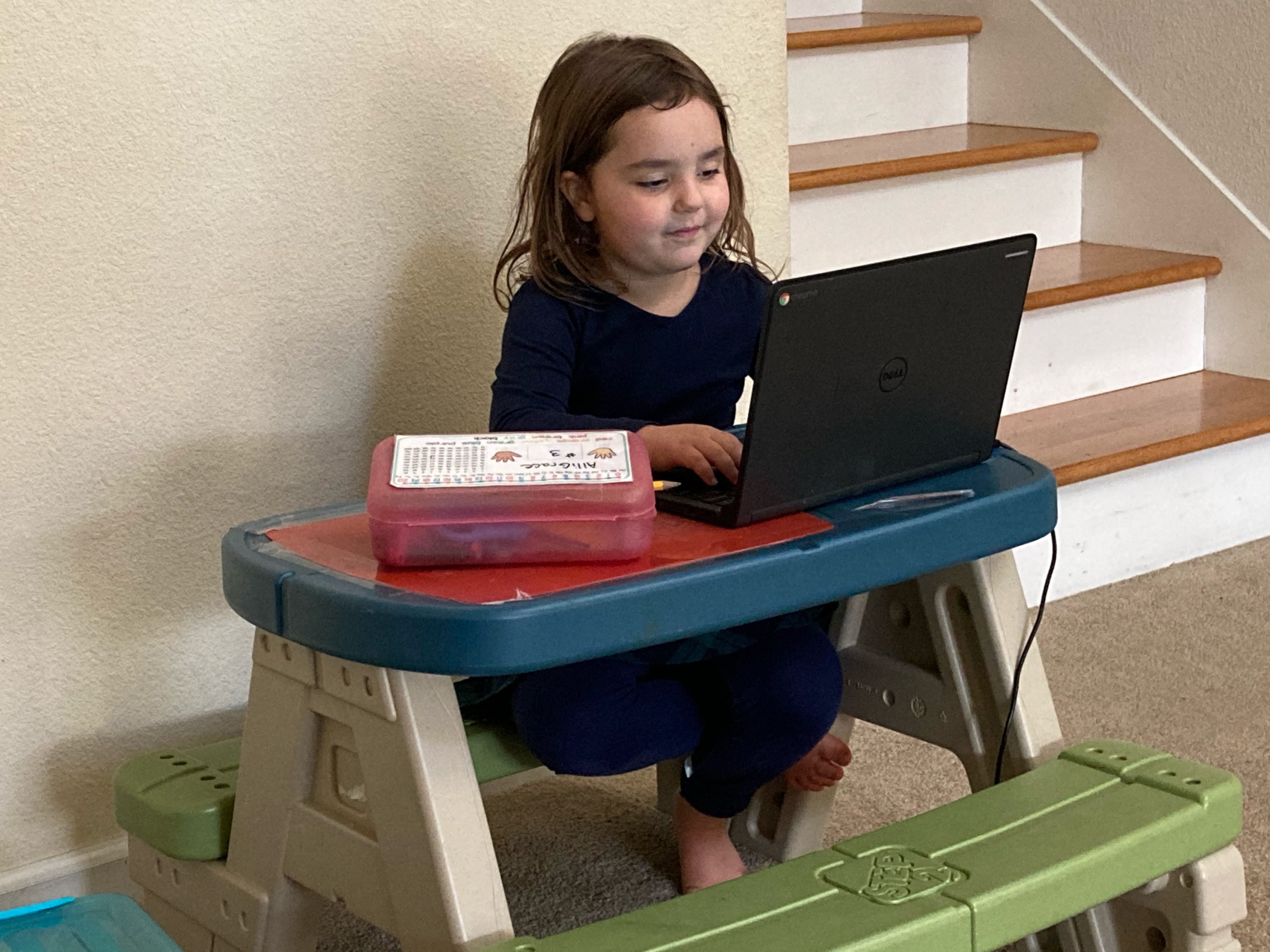

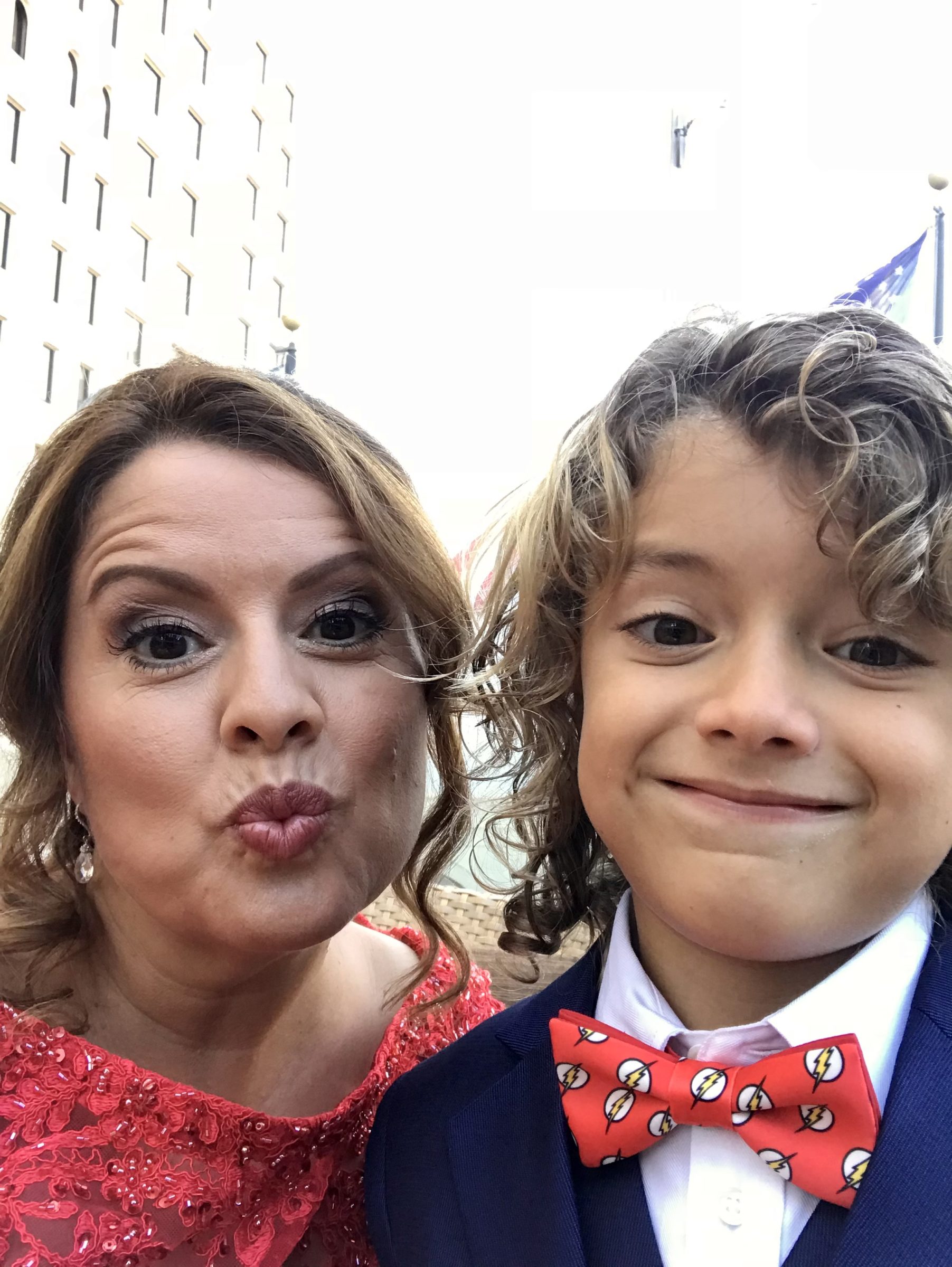

Katina Rondeau with her son.

The Lean In report found mothers with young children have arranged work hour reductions that are four to five times greater than fathers in the age of COVID.

Katina Rondeau, a single mother, is among women in the workforce who have reduced hours and taken a pay cut during the pandemic. She teaches an independent study program at Hilltop High School in San Diego for students who are not able to succeed in the regular classroom, and was named Teacher of the Year in 2007 and 2018 by her district.

“Women carry the children during pregnancy – and also during the pandemic.” Katina Rondeau, Sweetwater Education Association

She was managing to teach remotely with her 9-year-old son at home, says the Sweetwater Education Association member. But then her school requested that in addition to teaching online classes, Rondeau come to campus each day to work with students doing credit recovery under a “canopy” that offered connectivity to their devices. She had no one to care for her son, so she declined the extra hours after already taking a 30 percent pay reduction, due to cuts made to her program during the pandemic.

“I asked myself, ‘Is it really worth it?’” recalls Rondeau, who has a master’s in special education. “If we were to be called back, my son would be able to go to school in a hybrid model just a few days a week and I would be expected to work every day. How is that possible without child care? I was also worried about exposing my child — and myself — to COVID. So I decided to continue working at home, have my child stay home, and work fewer hours.”

Union protection helps

Tracy Maniscalco

CTA chapters are demanding safe working conditions. And by working remotely, some teachers like Rondeau are able to juggle teaching and caring for their own children in a safe manner. But even for those working remotely, teaching and taking care of young children can be overwhelming, and some are either quitting or taking an unpaid leave of absence.

Tracy Maniscalco, a chemistry teacher at Montgomery High School in Santa Rosa, was teaching remotely from home, caring for her 5-year-old daughter and 7-year-old son, and burning the candle at both ends.

“I would Zoom with my own students when my children were napping, and do lesson planning after my kids went to bed. I was up until 2 or 3 every morning. It was not sustainable. I was trying to do it all — but after a while I just couldn’t. One time my son started crying in the middle of my Zoom class because he had a rock stuck up his nose. My high school students thought it was hysterical, but it was stressful.”

“I love my students, but I have to prioritize my family and my mental health.” – Tracy Maniscalco, Santa Rosa Teachers Association

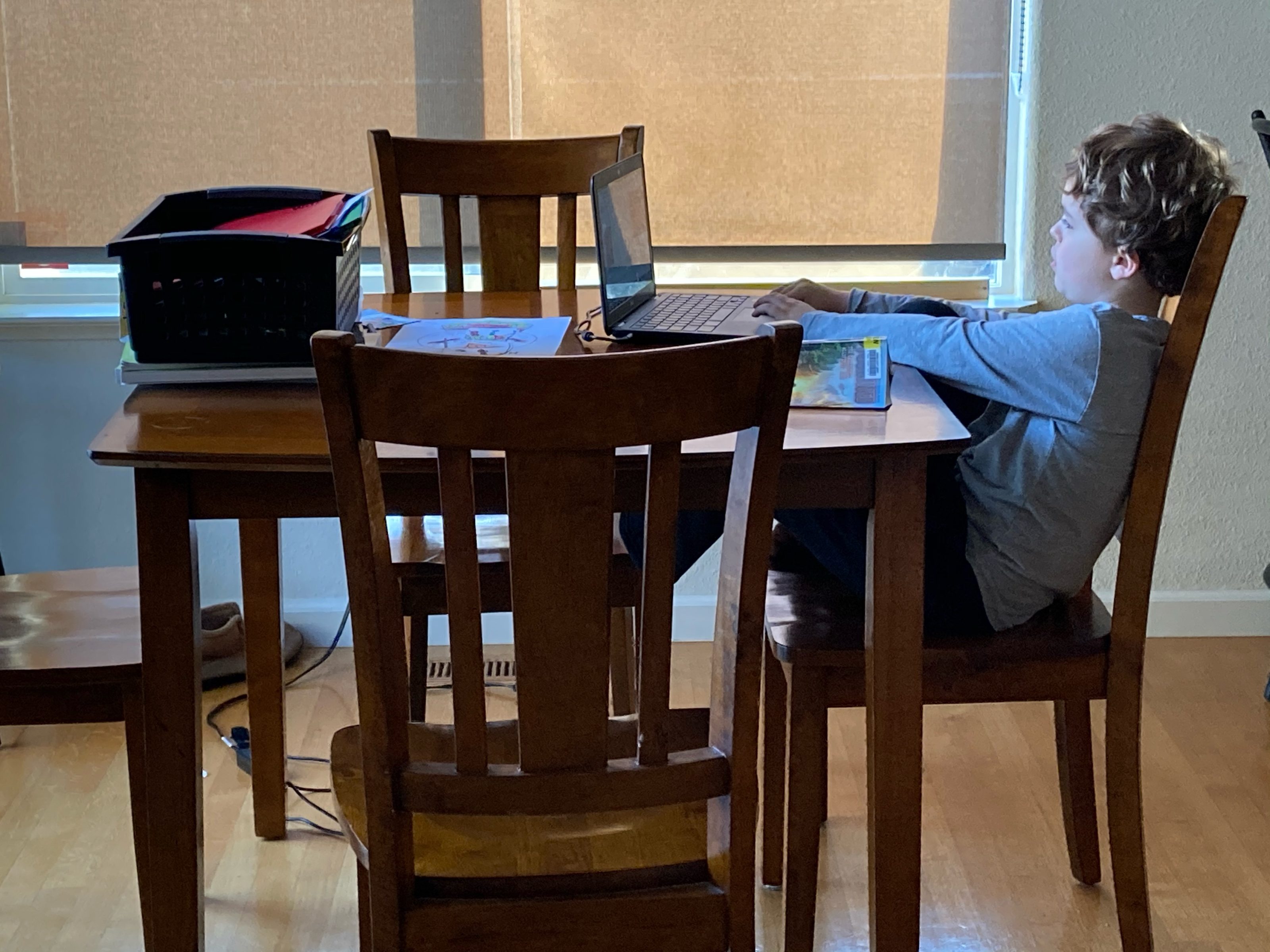

Maniscalco’s son learning remotely.

Maniscalco’s daughter attends online class.

She found support from the Santa Rosa Teachers Association, which negotiated a memorandum of understanding allowing teachers to go on unpaid leave during the pandemic. She had initially resigned to care for children and coordinate their distance learning. But after the MOU was negotiated, the district rescinded her resignation and allowed her and others to take a year’s personal leave.

“Our union fought for us,” she says.

She plans on resuming teaching next August, and hopes it is safe for her children’s school to reopen by then. She and her husband, who works in the medical field, decided together that due to her teaching experience, she was the logical choice when it came to who would stay home.

Stacey Strong Ortega, a member of the Orange Unified Education Association who has taught first grade for 21 years at Nohl Canyon Elementary School in Anaheim Hills, is also on leave.

Stacey Strong Ortega

Strong Ortega has three children — twin girls in first grade and a son in fourth grade. Their school in Westminster resumed in-person learning two days a week, for a few hours each day, combined with distance learning. But her son has asthma, which puts him at risk for COVID complications, so all her children are learning remotely.

All was going well when she was teaching from home. Her family created a routine and were, in fact, “rocking it,” says Strong Ortega, who shares parenting duties with her husband. Then her district announced in-person learning would resume at the end of September, and teachers had to come back.

“Teachers were understandably hesitant,” she says. “A lot of teachers had children at home and were stuck between choosing their family over their job and financial security. Also, a lot of classrooms, especially the school where I was at, have no windows. The buildings are ’70s style, with pods that all share the same air. It was scary.”

After Stacey Strong Ortega finished teaching remotely, she and her children worked together in their living room.

Teachers feared for their safety but were told that since their contract did not have language allowing teachers to work from home during a pandemic, they must return. Strong Ortega would have preferred to continue working at home. But her district, unlike surrounding districts, did not offer educators that choice. So, she went on leave.

“In addition to being a financial kick in the pants, it’s difficult because being a teacher is my identity and who I am,” she says. “I strongly believe that unions need to continue to stand up and fight for what is right and protect their members.”

Martinez, the chapter president who quit, says that nearly all the teachers at her single-school K-8 district were in favor of returning to school. But her chapter members supported her decision to resign, she says, and she remains friendly with them.

Families are hurting

Women educators who have quit or taken unpaid leaves from work say they are relying on their savings, spending less, and trying to live on a tighter budget.

“In addition to being a financial kick in the pants, it’s difficult because being a teacher is my identity and who I am.” – Stacey Strong Ortega, Orange Unified Education Association

“We use a lot of natural lighting to cut down on electricity,” says Rondeau. “We are not spending as much, and I’m not commuting and driving around, so I’m not paying much for gas. It’s difficult financially, but I am allowed to be home with my child. Many families don’t have that luxury.”

Being on a leave of absence has been tough, says Maniscalco, who says that living on her husband’s income makes her feel like “a high-tech 1950s housewife” at times.

“Our income dropped dramatically, which forced us to cut all nonessentials, but thankfully we had an emergency fund, so we were able to handle my not working for a year. I spent time this summer taking free budgeting seminars, figuring out meal planning and learning to cook. When we both worked, we had the luxury of takeout meals. Now I’m cooking all the time, which is ironic, because even though I’m a chemistry teacher, I’m not the best cook.”

Erika Martinez

Martinez says her family is “cutting corners,” tightening their belt and relying on savings. Her husband has taken on side jobs and extra hours at his job to make ends meet. She has also taken on a side job scoring writing assessments for a testing company that prepares students for standardized tests on the East Coast.

“Compared to what I was making, it’s nothing. But every little bit helps. It’s something I can do at home, and it keeps my mind active.”

What’s the impact on society?

With women being pushed out of the workplace, experts fear that decades of progress will be undone in terms of gender pay equity and opportunity.

“Women’s disproportionate responsibilities at home were already a major contributing factor to their lower pay and difficulty advancing at work,” asserts a December story at vox.com. “Now men will have an even greater advantage when it comes to increased opportunities, promotions and raises.”

“It’s not setting a good example for our students or our children in terms of women taking a hit and being considered expendable. How long will it take to get our jobs back when this is over? Will our jobs be there when this is over?” – Stacey Strong Ortega

“It’s unfair,” says Rondeau. “Women carry the children during pregnancy — and also during the pandemic.”

Single mother Katina Rondeau with her son.

The long-term consequences for those who quit or go on leave include less retirement money for the future. Teachers who go on personal leave have their retirement funds put on hold while they are not in the classroom. And many already had their retirement held while on maternity leave.

Teachers pushed out during the pandemic may decide not to return to teaching when they reenter the workplace, which will no doubt exacerbate the teacher shortage.

Strong Ortega believes that women exiting the workforce is not just bad for women — it’s bad for everybody.

“It’s not setting a good example for our students or our children in terms of women taking a hit and being considered expendable,” she says. “How long will it take to get our jobs back when this is over? Will our jobs be there when this is over?”

Martinez, who has a master’s degree, plans on rejoining the workforce, but isn’t sure whether it will be as a teacher.

“I want to be a role model for my daughter and show her a woman can succeed as much as a man. But being a woman is hard. We have to juggle it all. We wear many hats. We have many roles. And the pandemic is stretching us very, very thin.”

Featured photo: Getty Images

Credit: rosietheriveter.com

Educators: The Union Difference

In a review of essential workers in May 2020, the Economic Policy Institute summarized the benefits of unions in a pandemic, including protection for expressing concerns about unsafe environments, collective bargaining to help obtain PPE and other safety measures, higher likelihood of having expanded leave and health care coverage, etc. (Essential workers were defined as those working in “essential industries,” mostly in health care, food and agriculture, and the industrial, commercial, residential facilities and services industry.)

The review showed that only 12 percent of essential workers are covered by a union contract, and some of the highest-risk industries — those more likely to employ women, people of color, and low-income workers most impacted by the pandemic — also have the lowest unionization rates, including health care at only 10 percent, and food and agriculture at only 8 percent.

By comparison, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in January 2020, the unionization rate was 33.1 percent in education, training and library services.

This means educators have better union protections than other female-dominated industries. “There is no better time to have a union,” says the Century Foundation in a June 2020 review of workers’ collective power during COVID-19. “They are helping workers survive the pandemic by negotiating safety standards, pay improvements, and contract provisions that help blunt the effects of layoffs, as well as serving as a powerful voice in local, state, and national conversations about workplace issues.”

From the Horace Mann Educator Health & Well-Being Study