Photos by Scott Buschman

Years ago, nearly every school had a nurse, recalls Dr. F. Ndidi U. Griffin-Myers, director of the School of Nursing at Fresno State University, which has a school nurse credential program.

But times have changed, observes the California Faculty Association member. Due to budget cuts, the number of school nurses has dwindled in California. Nurses are now often responsible for multiple schools and large populations of students, coinciding with more students with serious health issues attending schools.

F. Ndidi Griffin-Myers

“In the old days, you bandaged a kid with a scrape or handled an occasional emergency, but now we are talking about feeding tubes, diabetes, epilepsy, students with heart problems, severe food allergies, and acute and chronic illnesses,” says Griffin-Myers. “The lack of school nurses in California puts children at risk.”

In 2010, California had 2,187 students per school nurse, according to the National Association of School Nurses. By 2015, that ratio rose to 2,784:1, with ratios varying wildly among counties, according to Kidsdata.org. During 2015 in Santa Cruz County, for example, the ratio was a shocking 8,920:1; in Tuolumne it was 6,122:1; and in Monterey, 6,574:1.

In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that every school have a nurse. Twenty-two states require school nurses, and 15 states require staffing ratios. California is not among them, despite state and federal laws that require districts to meet the medical needs of students with disabilities and health conditions.

A 2015 study by SRI International, involving researchers from Sacramento State University, UC Berkeley and University of Wisconsin-Madison, examines how California schools are meeting health service needs during the school day. The study concludes that a large population of children lacks access to minimal health services during the school day; that only 43 percent of school districts employ a school nurse; and that 1.2 million California students attend schools in the 57 percent of school districts without one.

“It is not a stretch to speculate that all children [in districts without school nurses] — and especially children with special health care needs — are experiencing poorer health and academic outcomes because they don’t have access to school nurses,” states a summary of the report.

Griffin-Myers believes the situation may worsen.

“As more people lose health insurance, we are going to see more students who will rely on schools for health care. So we are going to need more school nurses. It is important that nurses speak up, because students are unable to advocate for themselves.”

While working harder, school nurses have found ways to help students stay healthier through prevention, education, community partnerships, and a strong dose of can-do spirit.

Advice just a phone call away

How do 12 school nurses help meet the needs of 54,000 students in the Corona-Norco Unified School District? School nurses started a help line that allows for telephone triage, so serious problems get instant attention.

Nurses rotate the position, and when a nurse is on call, they are responsible for answering questions from office staff, health clerks who are trained to provide first aid, registration clerks with questions about immunizations, and administrators and parents. They confirm activities and procedures for nurses out in the field.

It was nurses who dreamed up the call center over a decade ago, when school nurses began to feel overwhelmed.

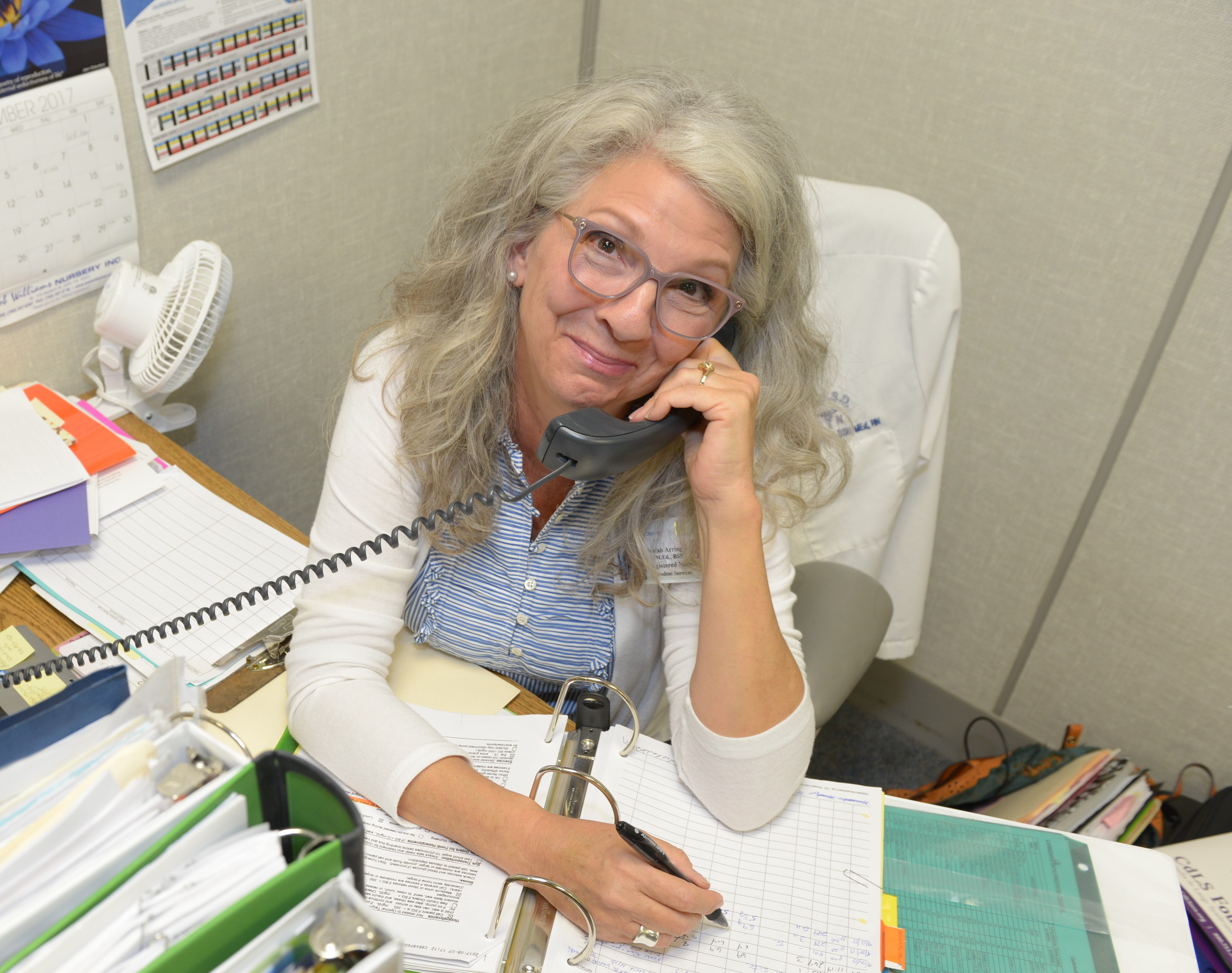

At a Corona Norco Unified School District office, nurse Norah Arrington works a shift on the help line.

“This help line allows the school nurses to do the work they need to do instead of fielding phone calls all day,” says Norah Arrington, named 2017 School Nurse of the Year by the San Bernardino Riverside County School Nurses Organization. “It allows for some of our diabetics who can inject their own insulin to be supervised by well-trained health clerks, who call in to verify insulin dose based on carb count and blood sugar. We take lots of calls about diabetics to determine a course of action during the day by looking at their health plan and physician orders.”

On-call nurses typically receive between 30 and 50 calls during a school day.

“Advice nurses can access health plans for all district students. We ensure schools meet the requirements of public health laws and immunization laws. And we can tell office staff when it’s time to call 911.”

The Corona-Norco Teachers Association member remembers a time when nurses ran all over the district from emergency to emergency and couldn’t get there fast enough.

“It could take us 30 minutes to get across town. This is much easier, and it’s the next best thing to being there,” Arrington says.

Improving vision, wiping out flu

Lynda Boyer-Chu had a vision: to make sure students without good eyesight could see. She organized a vision-screening program for all freshmen at George Washington High School in San Francisco.

When she began working at this school of 2,000 students, she noticed some of the students were squinting to see. San Francisco Unified School District only screens first- and fourth-graders on a routine basis, but many high school students were arriving too late for that, or their vision had worsened and their parents were unaware of the problem due to lack of screening.

Lynda Boyer-Chu, a nurse at George Washington High School in San Francisco, gives a flu shot to Taylor Miller.

“Seven years ago, I realized I had the capacity to screen all ninth-graders due to my accepting nursing students from City College or University of San Francisco as interns,” Boyer-Chu says. “Because I’m not fluent in other languages but a substantial number of our parents speak Chinese or Spanish, I always ask for and usually get bilingual nursing students.”

Approximately 25 percent of students do not pass the vision screening, and when that happens she calls their parents. If they are unable to afford glasses, she offers referrals and resources from partnerships with LensCrafters and the nonprofit Children’s Vision First to provide free eyeglasses.

Boyer-Chu also wanted to reduce absenteeism due to flu, so she implemented a vaccination program targeting ninth-graders. Washington High is the only San Francisco school that offers the flu vaccine on campus, thanks to the help of nursing students. In addition, Boyer-Chu created a partnership with UC San Francisco dental students to provide dental screenings for English learners and students with special needs, who often lack access to dental care.

“School nurses are at the front lines for public health,” says Boyer-Chu, United Educators of San Francisco. “We play a role in creating a healthier society.”

Preventing obesity

A record number of students are overweight and at risk of developing diabetes and heart problems. In fact, some experts say today’s youth will live shorter lives than their parents.

Nancy Semerjian, a school nurse at Limerick Elementary School in Winnetka in the San Fernando Valley, hopes to change that grim prognosis by helping students stay fit and eat healthier, while having fun at the same time.

At Limerick Elementary in Winnetka, nurse Nancy Semerjian shows students how to use exercise equipment.

She joined the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, a national program dedicated to keeping students physically active and nutritionally aware. With nearly $5,000 in grant money from Healthier Generation and from Kaiser Permanente, she converted a classroom into a circuit gym for students. There are punching bags, treadmills, balance pillows, power ropes, bike pedals, hula hoops, yoga mats and yoga classes. Students use the room an hour per week and sometimes more, going from station to station.

“Oh my gosh, the kids love it,” says the United Teachers Los Angeles member.

Semerjian had the campus designated as a “tasting school,” to sample healthy foods the district is considering serving. Students feel important being “taste testers” and have given thumbs up to turkey dogs, whole-grain bread and other healthy choices.

She created a five-minute workout for the student body first thing in the morning. Fifth-graders provide instructions over the intercom and play music as students march in place, do jumping jacks, squats and deep breathing. The routine has a calming effect on students and transitions them into work mode.

Semerjian started lunchtime walking clubs and provided pedometers to students through another grant from Fire Up Your Feet, an organization dedicated to movement. Last year, students walked a total of 5,000 miles at school, and their goal is to beat that record this year.

She partnered with Vision to Learn, a program that provides free eye exams and glasses for students, and is involved with the school’s social-emotional learning team, which helps students cope with bullying and other problems.

“Everyone thinks I put Band-Aids on and let children lie down in my office, but that is just a small part of my job description,” says Semerjian. “In addition to overseeing programs helping students stay healthier, I manage health plans of students with colostomies, catheters, feeding tubes and food allergies. The job of a school nurse is keeping students in school — despite health challenges they face. It’s a demanding job, but I love what I do.”

Helping teen moms and their babies

Thanks in part to the support of school nurse Yolanda Cuevas, Ana Perez had a healthy baby girl, finished high school and became a caring mother to Adamary, who is now 13 months old.

“Yolanda encouraged me to never give up, and I didn’t,” says Perez, now 20, who still regularly visits the school nurse who made such a difference in her life.

Yolanda Cuevas with Ana Perez and daughter Adamary. Cuevas helped Perez have a healthy pregnancy and stay in school.

Cuevas manages the Nurse-Family Partnership Program in Los Angeles Unified School District, and her territory includes South Los Angeles, where Perez lives. The program was created by Dr. David Olds, whose research found that helping women early in pregnancy prevented their babies from being born prematurely due to factors such as smoking, drugs, malnutrition or abnormalities caused by fetal alcohol syndrome.

“My goal is to help teens deliver healthy babies, see them graduate from high school and become self-sufficient,” says Cuevas, a member of United Teachers Los Angeles. “We try to prevent high-risk behavior through education for pregnant students who range in age from 11 to 19, enrolled in LAUSD. That includes students who dropped out. We assist in bringing them back to school.”

LAUSD is the only school district in the nation with this program. It is an expansion of the Los Angeles County Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) Program and is funded by the California Home Visiting Program. There are 4.5 positions devoted to the program, says Cuevas, and referrals are made by school nurses, counselors, teachers and administrators.

“We don’t tell students what to do. We provide them with information and explain that school nurses are mandated reporters, but everything is kept confidential. Sometimes we meet before they have told their parents. We encourage participation in the sessions by parents or the father of the child — if they are comfortable doing so, and willing.

“The NFP model is a home visitation program, but we accommodate students and meet with them at school on occasion or sometimes in a park. Our nurses are flexible and nonjudgmental. We don’t know what these students have gone through.”

For the first month, nurses meet with the pregnant teen weekly, to assure she has a doctor, is keeping prenatal appointments, taking prenatal vitamins, making healthy choices, and staying in school. Later, visits drop to twice monthly. After delivery there are weekly visits for six weeks, which continue until the baby is 2. Nurses help the young moms with birth control and sexual health.

“It is rewarding to see these young girls mature,” says Cuevas. “We have had 65 girls since this program started in 2012, and about 96 percent of them graduate high school and go on to college and vocational school. They want to do well, for their children.”

Perez plans to go to college and would like to become a nurse, like her mentor.

“It’s hard being a young mom,” she says. “But it’s been much easier having someone like nurse Yolanda to support me.”

Need a Nurse?

1.4 million

Approximately 1.4 million school-age children in California are considered to have a special health care need, which includes chronic conditions such as allergies, heart problems, seizure disorders or diabetes. Many of these children do not have access to minimal health services during the school day.

43%

43 percent of California school districts employ school nurses.

1.2 million

There are 1.2 million students in the 57 percent of state school districts without a nurse.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment