Photos by Scott Buschman

Highway 198 in central California is more country road than highway. It meanders through fields and farmland that separate the tiny towns of Huron, Coalinga and Avenal.

“You drive through fields, and there’s a cow town. Then more fields and another cow town. And more fields and another cow town,” says West Kings County Teachers Association President Amy Wilkinson, describing the route to Avenal, furthest from Fresno.

What strikes a visitor first is the isolation of each community; second is the poverty. The combination creates enormous challenges for these rural school communities, where most employment means work in the fields or correctional facilities. Huron is one of the poorest areas in the state.

The small towns along Highway 198 are more than an hour away from the nearest city, Fresno, yet they share many of the problems facing urban areas: generational poverty, gangs, drugs, a high dropout rate. But they also are tight-knit communities where people help neighbors and celebrate milestones together.

“Teachers get invited to birthday parties, baptisms and graduations all the time,” shares Christina Monreal, a kindergarten teacher at Huron Elementary. “It’s like family.”

Teachers in rural areas play a crucial role in educating students about the wider world.

Christina Monreal

“We want to be a bridge from school to family and instill our students with pride,” says Monreal. “Doctors, lawyers, engineers and professional athletes are all products of this rural community — including my husband, who worked the fields and now is a civil engineer who consults with farmers he once worked for. Tough challenges can push students to become successful in life.”

While rural students and educators must deal with difficult challenges, as Monreal’s example shows, there are distinct benefits as well. Read on to learn how several committed educators in rural communities find creative ways to give students a 21st century education.

Small schools, big challenges

California has one of the largest rural student populations in the U.S., with more than 220,000 students attending rural schools, according to the California County Superintendents Educational Services Association.

Whether located in farmland, forests or deserts, rural communities share common challenges, such as limited access to medical care, food and employment. Many jobs that supported rural students’ parents and grandparents have dried up, such as factory work and logging.

Transportation in California’s rural districts eats up much of school budgets. In Coalinga-Huron Unified School District, some students ride the bus more than an hour each way to school. Huron parents, upset over the long bus ride to the district’s only high school in Coalinga, attempted to form their own district in 2017 in what locals called “Hurexit,” but were unsuccessful.

Recruiting and retaining school employees in rural communities is challenging, says Debra Pearson, executive director of the Small School Districts’ Association, and that includes teachers, bus drivers and mental health workers.

“For teachers, the pay scale is much lower, and teaching conditions are much more demanding, especially when you have multigrade classrooms. Many teachers come to rural areas their first year, then leave for better-paying jobs, so turnover is high.”

Students in rural schools may lack access to advanced coursework. Many work to support their families instead of participating in extracurricular activities, putting them at a disadvantage when applying to college, reports the National Center for Education Statistics. They are less likely to attend college due to poverty and a lack of colleges in their vicinity.

“The closest community college could be three-plus hours away,” says Pearson. “I grew up in Modoc County, and the closest college was 170 miles away on a two-lane highway.”

Modoc, Humboldt and Siskiyou counties are among those that have relied upon the federal Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act (SRS), which provided extra funding to rural school communities that once relied on the timber industry. However, it expired in 2016 and has not been renewed, prompting fears of more cutbacks and school closures in some rural communities. Bipartisan support to reauthorize SRS funding in the next federal budget may help.

Close-knit communities

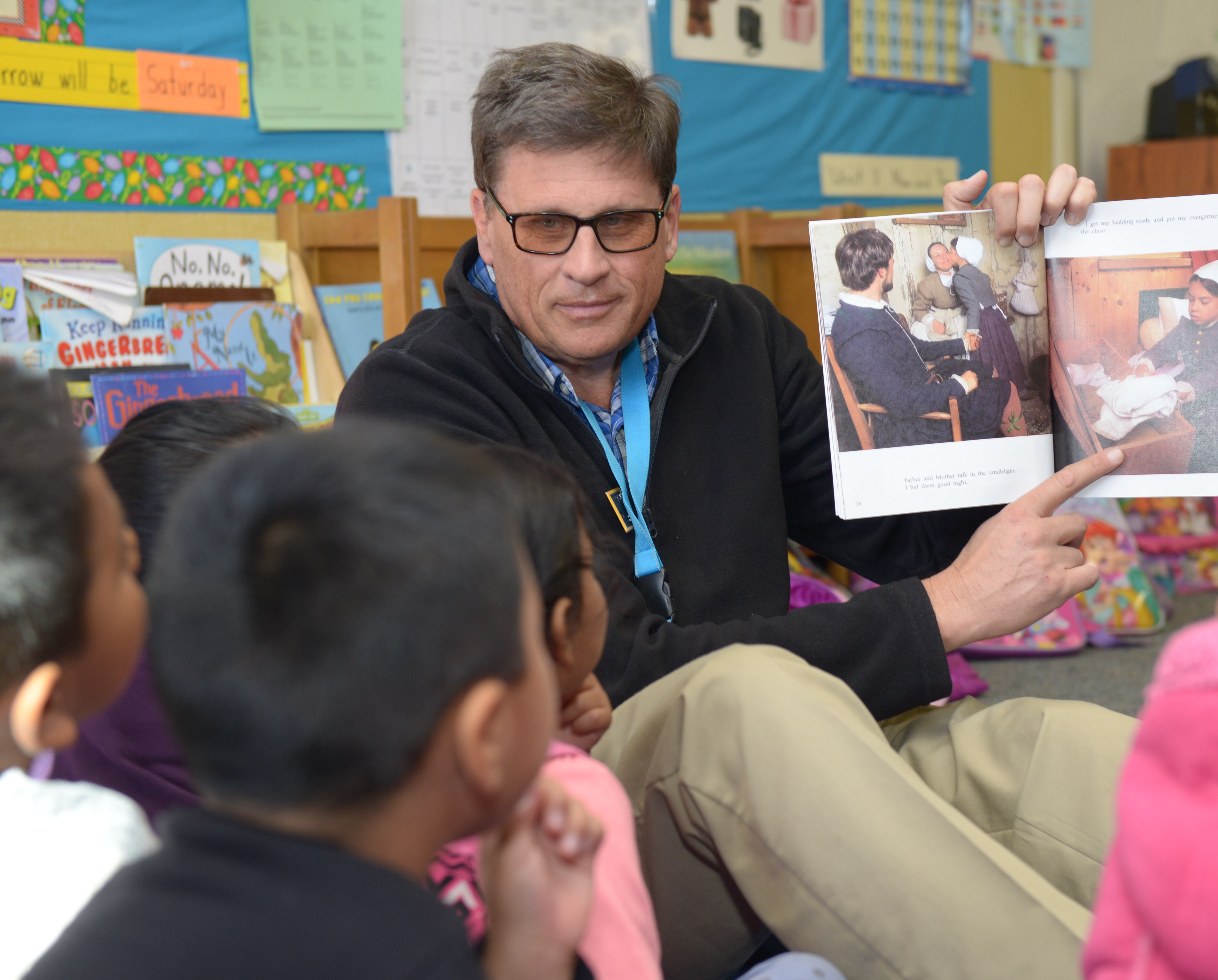

“We are so isolated,” says Tom Wells, president of the Coalinga-Huron Unified Teachers Association (CHUTA). “As teachers, we want our students to discover the world, but that can be hard in our community, so our educators are always trying to bring the world to them.”

At Huron Elementary, Tom Wells reads to his students.

Field trips help, say Huron Middle School math and science teachers Pete Alvarado and Karrie Madrigal, who brought children to the Griffith Observatory and La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

The school provides clothing and food to students in need, making a point of offering these things discreetly. Caring and sharing extends to a newly created program called SMART, where administrators, teachers and counselors “adopt” students to offer them emotional support and inspire motivation. Staff credit this “relationship building” with a turnaround that brought the campus recognition in the state Schools to Watch – Taking Center Stage program.

Janine Wagner

Last year the high school graduation rate rose to 88 percent, says counselor Janine Wagner proudly. But a big challenge remains — convincing parents to allow their children to go away to college.

“I grew up here and went away to college,” says Wagner. “I try to highlight my experiences and let them know I survived, came back, and have been giving back to our community for 11 years. But many of our parents are fearful to have children leave home.”

Coalinga High School teacher Tom Lucero teaches real-world skills to journalism students, who produce an award-winning magazine and create weekly multimedia news broadcasts on YouTube. His drama students put on productions that entertain the entire town; school plays and football games are big sources of entertainment in rural communities.

Coalinga High School’s Tom Lucero with drama students during their rehearsal of “Grease.”

Lucero has taken students to Fresno for Broadway plays, and will take students to New York on a field trip. He comments that people in rural communities are generous when it comes to fundraising for these outings, even if they are poor.

Because rural schools are short on funding, they are continuously fundraising at school events, fairs and town festivals, holding bake sales, car washes and raffles. It’s a lot of work, but it strengthens educators’ ties to the community, say teachers.

However, when teachers reside in the rural town where they teach, it can feel as though they are living under a microscope, comments Lucero, a Coalinga resident.

“There’s no such thing as anonymity. People call me by name at the gas station, the grocery store and movie theater. Even the elementary students know me by name.”

Opportunities in agriculture and other fields

Almost 60 percent of students in rural schools in California are of color, many of them Hispanic and from families with ties to the agriculture or service industries.

Huron Elementary’s Christina Monreal, a CHUTA member, says her school recently started thematic instruction to provide English learners with a rich foundation using the Sobrato Early Academic Language Model, which incorporates units on farm crops, the power of the sun, dairy farming and other aspects of students’ everyday lives so curriculum is relatable, and students feel proud of what their families do. It has boosted achievement, she says.

At Avenal High, Zitlaly Soto and Hayline Gonzalez anchor the BUC news program, while educator Amy Wilkinson and cameraman David Moreno look on.

At Avenal High School, where Amy Wilkinson teaches communications, many students are the children of farmworkers. “They call Kings County the agricultural breadbasket of the world,” Wilkinson says.

Indeed, agriculture is a major industry for California. With 76,400 farms and ranches statewide, agriculture is a $54 billion industry that generates at least $100 billion in related economic activity, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

A 2015 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Purdue University estimates that nearly 60,000 jobs in the agriculture, food, renewable resources, and environment fields are available every year nationwide, yet only 35,000 graduates with agriculture-related degrees are available to fill them. Careers include food scientists, inspectors and engineers.

In Avenal, which claims to be the “Pistachio Capital of the World,” the school has partnered with the Wonderful Company — the world’s largest grower of tree nuts and America’s largest citrus grower — for its Wonderful Ag Prep program, which offers dual enrollment in West Hills Community College Coalinga and an opportunity to earn a two-year associate degree in high school. Upon graduating, students can either work for Wonderful or attend a four-year college to complete their bachelor’s degree in two years. These students also have guaranteed admission to Fresno State University.

Avenal High School agriculture teacher Ryan Fellows in the school’s citrus fields with students Angeles Estrada and Javier Romero.

The school has a Future Farmers of America club for raising livestock and a tractor mechanics class. Agriculture teacher Ryan Fellows teaches about horticulture in the school’s citrus fields.

“We are trying to create a college-going culture at school,” says Wilkinson. “And we encourage students to look at a variety of careers.”

Avenal teachers take students on field trips to visit colleges. And laptops are available for every student, which is important when students don’t have access to technology at home. It benefits the entire family, says Wilkinson, because parents use them for job applications and online courses.

“Our struggle is the same as many urban schools. We are just more remote,” says Wilkinson. “We struggle with gangs, drugs and poverty.”

There is also high teacher turnover, but Wilkinson isn’t leaving.

“I love these kids. It can be heartbreaking, because the poverty is so pervasive. But if they work hard, they can be the first student in their family to go to college. And I want to help with that.”

Shattering stereotypes

“There are a lot of misconceptions about rural schools,” says Michelle Rosenbloom Quirsfeld, president of the Mammoth Education Association (MEA). “People think that we are not up-to-date in our instruction or training because we live in a rural town.”

Mammoth Elementary School’s Michelle Quirsfeld reads with Piper Kastor.

Mammoth teachers are anything but country bumpkins, asserts Quirsfeld, a fourth-grade teacher at Mammoth Elementary School who also teaches cross-country skiing. “We are well educated and ahead of many schools in current practices.”

Located just minutes from the state’s largest ski resort, it’s not your typical rural district. Some affluent residents own second homes and enroll their children in Mammoth schools four or five months out of the year. Sixty percent of students are Hispanic, with a high percentage of English learners whose parents work in the service industry.

“There is not only a huge disparity but a significant achievement gap,” says Quirsfeld. “We spend a lot of time helping students catch up.”

MEA members have embraced a unique approach called “conferencing” where students work independently toward personalized goals, while the teacher makes time each day for one-on-one conferring. It is based on a program called Daily Café.

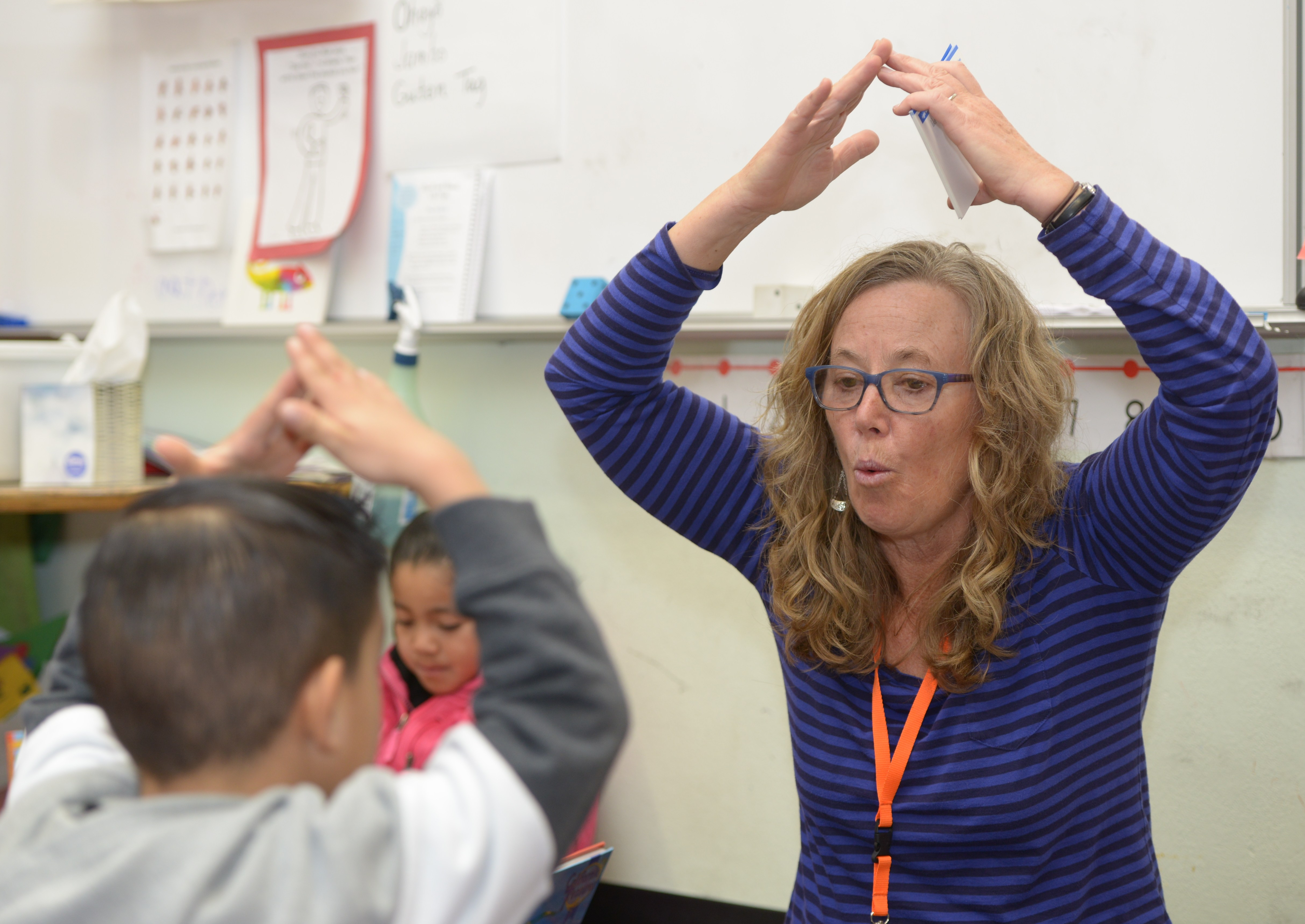

Mammoth Elementary School’s Judy Burgenbauch.

In Judy Burgenbauch’s first-grade classroom, a student discusses what he needs to do better — looking at the first letter of each word to determine its sound — and practices with his teacher. Meanwhile, other students work alone, quietly reading books and listening to books on computer.

“It’s nice being able to focus on one child at a time for a few minutes,” says Burgenbauch. “It helps a child reach his or her goals, and other students get valuable experience working independently to practice reading and writing.”

The district has a Spanish dual immersion program. Silvia Mendez, who teaches first grade, says it helps newcomers feel more connected to school and become literate in their primary language, building a foundation for success.

When the middle school finally received funding for a new computer lab, teachers decided it was not effective use of technology for students to leave their classrooms. Instead, they integrated technology into regular instruction, with laptops and multiple Smart Boards in classrooms. In Michelle McMillian’s Spanish class, student groups simultaneously create presentations and slide shows on four separate screens.

Michelle McMillian with student Davin Wolter at Mammoth Middle School.

“This is a model classroom,” says McMillian proudly. “Others are in transition.”

The school makes excellent use of the mountain: The elementary school offers snowboarding, downhill skiing and cross-country skiing PE classes and sports teams. There are also middle school and high school teams for these sports instead of classes. The ski resort and local community businesses contribute to the cost of PE classes and sports teams to make sure everyone can participate. Classes and teams are coached by teachers and community members; some are taught by Mammoth Mountain ski instructors. School buses transport students to the base of the mountain.

Three-time Olympic medalist Kelly Clark developed her snowboarding talent on the slopes of Mammoth Mountain. Four other snowboarders who competed in the PyeongChang Games call Mammoth home, including gold medalists Shaun White and Chloe Kim.

PE class for Mammoth Elementary students.

“This is a great place to live and a great place to teach,” says Quirsfeld, gesturing to the three adjacent campuses against the postcard-perfect backdrop of Mammoth Mountain. “It’s beautiful and friendly. It’s always exciting to think we could have a future Olympian in our midst at this very moment. You never know.”

Versatile and hardworking educators

Marianne Boll-See teaches 10th-grade English, 10th-grade honors English, 12th-grade English and yearbook at Golden Sierra High School in Garden Valley, El Dorado County. Teaching several different classes is not unusual, says Boll-See, president of the Black Oak Mine Teachers Association. For example, Larry Highberger teaches auto shop, welding, construction and woodworking, and runs a lumber mill at the school.

Marianne Boll-See with her classroom at Golden Sierra High School behind her.

“Rural teachers wear a lot of hats,” says Boll-See. “We are very versatile and work hard. With a small population, we often have several grade levels in one classroom.”

Like many rural schools, enrollment has been declining, resulting in less ADA funding. The high school had 800 students in 2008 and now has fewer than 350.

Employee health care costs are higher — and salaries are lower — than in surrounding districts, resulting in teacher turnover, says Boll-See, who rents a room in her home for additional income.

Middle school students from K-8 schools were brought to the high school in the cash-strapped district to save money. Despite concern about younger and older students mingling, there haven’t been problems.

The school district has a higher than average percentage of students with special needs, says Boll-See, which has further impacted the budget. Families of these students are attracted to the slower-paced lifestyle. Transportation costs also eat up much of the budget. Some students ride the bus for 45 minutes to and from school.

Working in a rural school is not for wimps, she says.

“We choose to live here. We work hard. We have a lot of pride. We are a family. We don’t let children slip through the cracks. We have harsh weather and beautiful scenery that helps us create interesting lessons. And we love what we do.”

Vital Statistics

Number of California students in rural districts: 220,000

Source: California County Superintendents Educational Services Association.

Percentage of:

- California public schools classified as rural: 11.5

- State education funding to rural school districts: 3.0

- Minority students in California rural school districts: 57.5

- English learners enrolled in California rural school districts: 20.9

- Special education students enrolled in California rural school districts: 8.8

- Students in California rural school districts eligible for free/reduced-priced meals: 59.1

Source: “Why Rural Matters 2015-2016: Understanding the Changing Landscape,” a report of the Rural School and Community Trust.

Making Professional Development Accessible

Read how CTA’s Instructional Leadership Corps is bringing professional development to remote rural areas here.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment