Photos by Scott Buschman

“Save Mono Lake.”

For years it was a slogan on bumper stickers and T-shirts. Now the famous body of water in remote Mono County is in the process of being saved, and it provides educators in the lakeside community of Lee Vining opportunities to offer dynamic science curriculum and important life lessons.

In fact, it’s the perfect teaching tool for educating students about:

- Preserving Earth’s natural resources.

- What can go awry when humans interfere with Mother Nature.

- Geology and the creation of tufa formations.

- Self-contained ecosystems.

- The delicate art of riparian restoration.

There are also valuable history lessons about political organizing and how it made a huge difference in the small community decades ago, long before the Internet and social media existed.

Brianna Brown

“We are so lucky to be able to use the outdoors and Mono Lake as an outdoor classroom,” says Brianna Brown, president of the Eastern Sierra Teachers Association (ESTA), adding that schools throughout the Eastern Sierra transport students by bus for annual field trips to Mono Lake.

“In addition to being able to study soil samples, rock samples and water samples, history is all around us, including fossils and petroglyphs from Native American tribes,” says Brown, who teaches 25 miles away in Bridgeport. “And the story of our lake is full of valuable lessons about preserving our planet for future generations.”

An outdoor classroom

At the Mono Lake Visitor Center, teachers Yvette Garcia and Julia Silliker, both ESTA members, explain to middle school students from Lee Vining Elementary School (K-8) that the ancient lake visible behind them was formed when Mono Lake was filled with glacial runoff nearly 12,000 years ago.

Yvette Garcia

The hills on the north, south and east sides of the basin are all of volcanic origin. The Mono Craters, 24 domes of rhyolite (volcanic rock) that have erupted over the last 40,000 years and as recently as 700 years ago, form the youngest volcanic chain in North America.

“Rising magma caused explosions of lava and superheated water to create craters and domes,” says Garcia.

Black Point, a striking feature on the northwestern shore, and Negit and Paoha islands are also of volcanic origin. The islands contain vents, hot springs, fumaroles and mudpots from their volcanic beginnings, which can be viewed from boats.

“Can everyone see Panum Crater?” asks Silliker. Students crane their necks to see the rim of the crater — a volcanic cone that is part of the Mono-Inyo Craters, a chain of recent volcanic cones south of the lake and east of the Sierra Nevada.

Next, students look for an osprey, a large fish-eating bird of prey often called a “sea hawk.” Nesting birds now include California gulls, snowy plovers and 79 other species of water birds.

Julia Silliker and Yvette Garcia with their students at Mono Lake.

Students learn that there are 14 different ecological zones, more than 1,000 plant species and roughly 400 vertebrate species within the watershed, and that the Mono Basin area is one of the state’s richest natural areas. Lake life includes algae, brine shrimp and alkali flies, but no fish.

Four streams that flowed into Mono Lake were diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1941, wreaking havoc on the surrounding ecosystem. Riparian vegetation died, fisheries were destroyed, occasional floods tore through the dry floodplains, and the lake’s water level dropped precipitously. In recent efforts to restore the area, new trees have been planted and limited water is flowing through several streams. Some classrooms hatch trout from eggs and release them into the streams.

A small group of people calling themselves Kutzadika’a inhabited the region before European settlers. Students frequently find their arrowheads, and are asked to leave them in place to comply with the Archaeological Resources Protection Act.

The name Kutzadika’a means “fly eaters.” Some Native American families in the area demonstrate basket weaving and hoop dancing to students and other groups at the Visitor Center. Some Lee Vining students have even eaten fly larvae at these events, which were a rich source of protein for native tribes.

Building a lesson around tufa towers

Ironically, the lake’s demise led to it being a tourist attraction for “tufa towers,” or calcium carbonate spires and knobs formed by interaction of freshwater springs and alkaline lake water. The towers grow only underwater, and some grow to a height of 30 feet or more. The reason visitors can see so much tufa now is that the lake level fell dramatically after water was diverted to Los Angeles. To protect these fragile formations, the California Legislature established the Mono Lake Tufa State Natural Reserve in 1981.

Mono Lake’s tufa towers inspire chemistry lessons in Julia Silliker’s class.

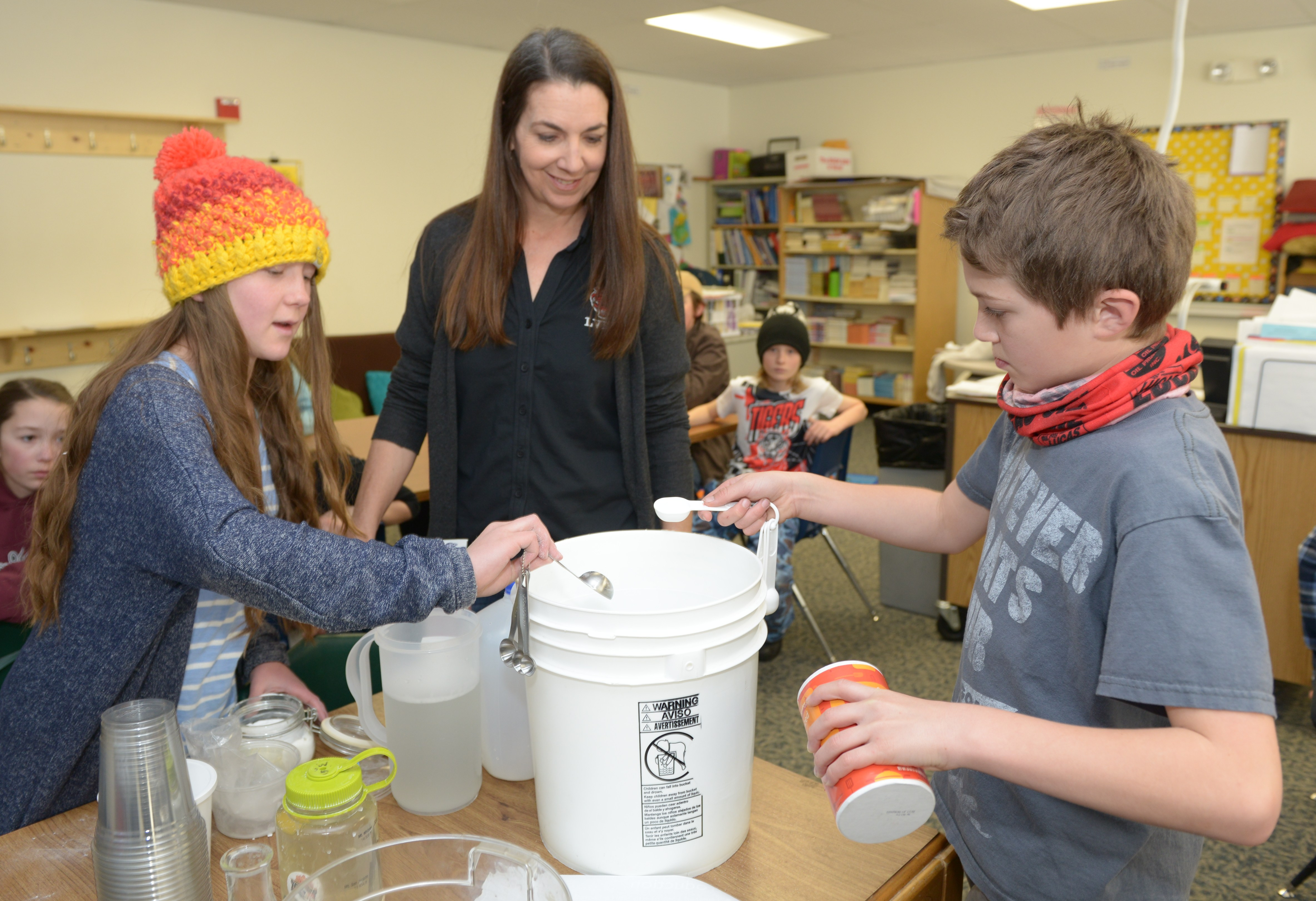

The tufa towers inspire chemistry lessons, and students create their own “lake water” and “tufa towers” in the classroom with Garcia and Silliker, to better understand the process.

Within Mono Lake’s waters are dissolved sodium salts of chlorides, carbonates and sulfates. The water is extremely salty because the water has no way out of the lake basin. Students replicate that with the following recipe: One gallon of pure water, add 18 tablespoons of baking soda, 10 tablespoons of table salt, eight teaspoons of Epsom salt, and a pinch of borax or laundry detergent. It’s not a perfect replication, because the lake water contains trace amounts of other chemicals. But it’s close enough.

To create mini-tufas, students add this water to dissolved calcium chloride, which results in tiny tufas forming at the bottom of their containers.

“What do the tufas feel like?” asks Garcia.

Students dip their fingers into the containers and reply that the tufas feel slimy, slippery and crusty all at the same time. One student compares them to feta cheese.

The teachers then provide actual lake water, and students perform the same experiments. They find no difference between the replicated lake water and real lake water results.

During the lab, Garcia and Silliker ask students why it is so important to restore a lake that was near death in their isolated mountain community.

“We don’t want salt to go into the air, because it makes the air bad,” says a seventh-grader. “We don’t want to breathe bad air.” (Toxic dust storms originating from dry lake bed areas in Mono Basin are among the worst in the nation.)

Mono Lake Committee educators Nora Livingston and Bartshe Miller conduct a remote lesson to students in another state.

In just a short time, students have been able to study geology, chemistry, volcanic eruptions, Native American culture, wildlife, and the politics of fighting pollution, without so much as leaving their immediate area.

“Teaching here is a scientist’s dream,” says Silliker. “We definitely live in a place that’s like no other.”

You don’t have to take students to Mono Basin for them to study it, because they can view the lake, wildlife and tufas online by connecting with the Mono Lake Committee. Also, committee members and volunteers conduct in-person field trips and weekend seminars for teachers and students. To learn more, visit monolake.org or call 760-647-6595.

A Story of Near Death and Revival

In 1941, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) began diverting Mono Lake’s tributary streams 350 miles south to meet the water demands of Los Angeles. Mono Lake lost 50 percent of its water, and its salinity doubled. The ecosystem began to collapse.

Islands, once nesting sites for birds including California gulls, became peninsulas vulnerable to mammalian and reptile predators. The rate of photosynthesis of algae, the base of the food chain, was reduced, while reproductive abilities of brine shrimp became impaired. Stream ecosystems unraveled. Air quality worsened as the exposed lakebed became the source of airborne particulate matter — violating the Clean Air Act — and toxic alkali dust storms arose on windy days from exposed salt flats. Ducks and geese disappeared.

By 1982, the lake level was more than 40 vertical feet below the pre-diversion level. Without intervention, Mono Lake was destined to become a lifeless wasteland.

At Mono Lake, students can study soil, rock and water samples, as well as fossils and petroglyphs from Native American tribes.

The Mono Lake Committee was created in 1978 to fight these conditions, joining with conservation clubs, schools, service organizations, legislators, lawyers and others to educate the public about the importance of saving this high desert lake. The committee grew to 20,000 members and gained legal and legislative power. In the late 1970s, “Save Mono Lake” bumper stickers could be seen on cars everywhere, as the lake came to symbolize the need to preserve and protect the environment.

The citizen action group has stayed strong by working with the public and a coalition of government agencies and nonprofits. Through negotiations, litigation and legislation, the committee’s efforts continue today.

The State Water Resources Control Board ordered the restoration of Mono Lake in 1994, with LADWP responsible for implementing the plan that included reopening a channel and controlling water release by remote control to take sediment downstream. The goal is to raise the water level, reduce salinity, eliminate dust storms, and reconnect the lake to springs and deltas.

Mono Lake will never be completely restored, however, because Los Angeles needs water. So eventually the lake will be 25 feet lower than pre-diversion level, the streams will carry less annual flow, and the former cottonwood-willow riparian forests will take 50 years to come back.

While ongoing restoration efforts have improved the Mono Basin ecosystem, the biggest lesson is that it is always better to prevent damage than rely on restoration.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment