Photos by Scott Buschman

The 17-year-old was out with friends at a department store when she succumbed to peer pressure. She grabbed a handful of rings from the jewelry display case along with several pairs of socks, and stuffed them into her purse without paying. Upon exiting the store, she was stopped by a security guard, arrested and charged with petty theft.

Now, a few months later, she is being judged by a jury of

her peers at Redondo Union High School’s Teen Court. The campus bingo room,

which looks like a real courtroom, is packed with students, some of whom are

called to jury duty. Unlike real life, they don’t have to wait around for

hours. They immediately step up to the jury box.

This live juvenile court has been a monthly occurrence on

campus for five years, thanks to Marie Botchie, a special education teacher who

serves as Teen Court coordinator.

“It’s a wonderful program,” says Botchie, a member of the

Redondo Beach Teachers Association. “What I love the most is that it’s a

restorative justice program instead of a punitive one. Our goal is to take kids

who have made mistakes and turn them around, so they can be a strong member of

their school and community — without becoming repeat offenders.”

Only first-time offenders are assigned to Teen Court.

Misdemeanor cases may include vandalism, assault and battery, sexual

harassment, reckless driving, and drug abuse.

The accused come from different high schools throughout the

Los Angeles area and are only identified by their first name. Before

proceedings begin, it must be determined that none of the jurors know the

accused and vice versa.

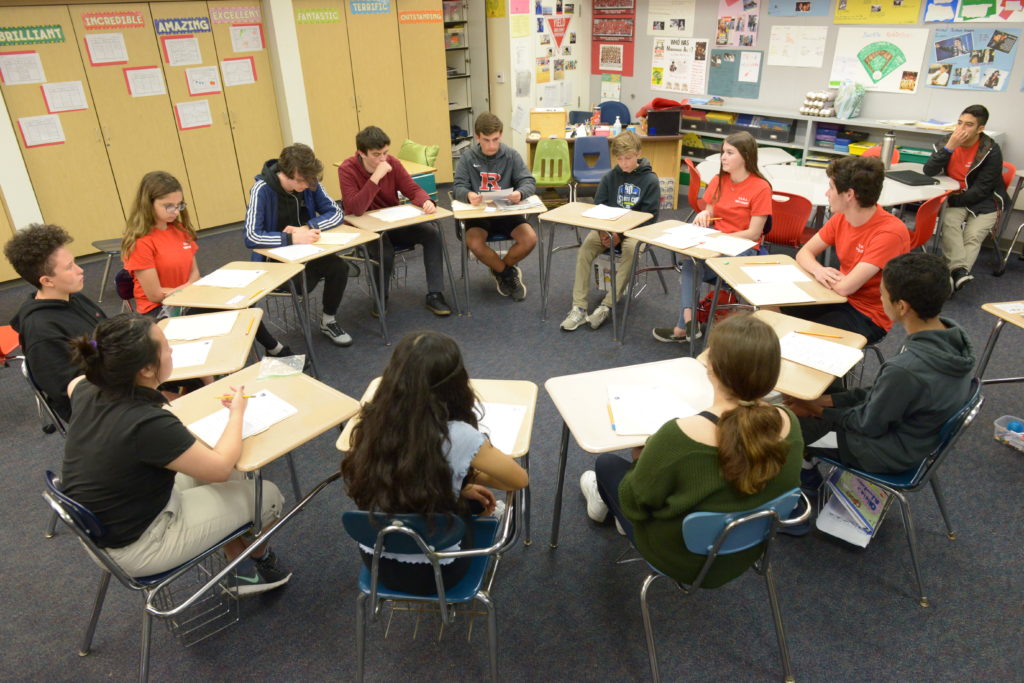

Students serving as jurors ask questions of the accused,

deliberate to determine guilt or innocence, and make sentencing

recommendations. Jurors have found students innocent on occasion. For example,

a student was accused of battery for placing a hot metal object on another

student at a party, but when jurors learned it was a game and no coercion was

involved, they found him not guilty.

To get a fuller picture of the accused, jurors can ask about

their grades, whether they abuse drugs, their plans for the future, and hobbies

or sports they enjoy.

Often, they will recommend community service aligned with

the offender’s interests, such as working in an after-school art program if

they enjoy art or receiving mentoring in a subject they are interested in for a

career.

“The goal is to get student offenders involved in positive

activities instead of taking things away from them,” says Botchie. “We want to

add good things to their lives.”

Botchie created a training program for Teen Court

participants at her school, who can fulfill requirements for government class

or community service through participation. She estimates that 500 students per

year are involved in the proceedings. Botchie also sponsors a Teen Court Club.

“The kids love it,” she says. “There is no place else where

kids who aren’t old enough to vote can be so involved in government. And these

are not mock trial cases; they are real. These jurors live very similar lives

to the accused. It’s the truest jury of peers you can ever imagine.”

There is always a judge to oversee proceedings, who in this

case is Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Eleanor Hunter. She bangs the

gavel three times to let students know court is in session, assigns students in

the audience to be jurors, and swears them in. The bailiffs, members of the

school’s Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC), escort the accused

into the courtroom, along with their parent or guardian.

The accused in this case is accompanied by her mother, who

hands her daughter a tissue to wipe away tears while the girl answers questions

about events leading to her arrest.

She readily admits that she is indeed guilty of stealing the

rings and socks, which she planned to give as birthday gifts to a friend. She

reveals that she gets A’s and B’s, except in math, which she currently has a D

in. She tearfully explains that her new friends pressured her to shoplift, and

she has never been in trouble before.

Her mother tells the courtroom that she did not approve of

these friends and felt they were troublemakers, but hoped her daughter’s good

influence would rub off on them. When a juror asks what consequences were

given, she replies that her daughter is grounded for several months.

In reply to jurors’ questions, the accused shares that her

mother is her best friend, and she is sorry for disappointing her. She says

that she enjoys playing on her school’s softball team, hopes to go to college,

and wants to become a nurse.

Jurors are surprised to learn the accused participates in a

Teen Court program at her school.

“So, you knew that stealing was wrong,” says a juror, and

the girl nods ashamedly.

Next, it’s time for deliberations, and the JROTC bailiffs

escort the jury to a classroom, where they must decide the fate of the teen,

who has pled guilty. The judge instructs them to make decisions based on

evidence and not let sympathy influence what they choose in the way of

remediation.

The 12 jurors vote to recommend six months’ probation, 30

hours of community service, staying away from the friends who pressured her to

steal, writing a letter of apology to the store owner, and participating in a

mentorship program for future nurses. She must also maintain her grades and

continue with math tutoring.

Jurors return to the courtroom and report their

recommendations to the judge, who agrees and decides to add a curfew during the

probation period. The judge reminds the accused that she is only a few months

away from turning 18, and the few months’ difference could have meant jail

time.

“Life is full of pressure, and you have to be your own

person, or you will find yourself back where you are now,” says the judge. “No

more stealing. No more lying to Mom. No more sneaky stuff.”

Afterward, the Teen Court Club debriefs the session. They

are surprised to learn the offender’s mother thought they were much too tough

on her daughter. They say they believe they acted fairly, compassionately, and

in the student’s best interest.

“I love Teen Court,” says Hannah Nemeth, co-president of the

club. “It’s an amazing program. We work with minors who commit real crimes, who

could potentially go to juvenile hall, and we are giving them a second chance.”

Co-President Sergio Godinez says he feels empowered by

participating in the democratic process. “Usually all we hear is ‘Wait until

you are old enough to vote,’ but this lets us make changes now within our local

community.”

Botchie is proud of the critical thinking, empathy and good

decision-making she has witnessed in participants over the years, and notes

that the recidivism rate for offenders is low. Of all the teens tried in 47

Teen Courts in Los Angeles County, only 5 percent commit another crime before

turning 18.

“We have no way to track them after that, but we often hear from their probation officer that they have finished probation, are back on track at school and generally doing well,” says Botchie. “Sometimes we hear they are attending college. I absolutely believe we are making a difference.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment