“Our new system motivates kids to not give up and keep trying, instead of putting their heads on the desk and not caring.”

—Sam Pereira, Monterey Bay Teachers Association

Sam Pereira is helping his district transition to what he believes is a more equitable form of grading, so that students in the Monterey Peninsula Unified School District are graded based on what they know, rather than on their behavior and ability to meet deadlines.

Sam Pereira

This approach, called “standards-based grading,” was piloted at Central Coast High School, a continuation school where Pereira teaches English. The district’s four high schools have committed to implementing it in the future.

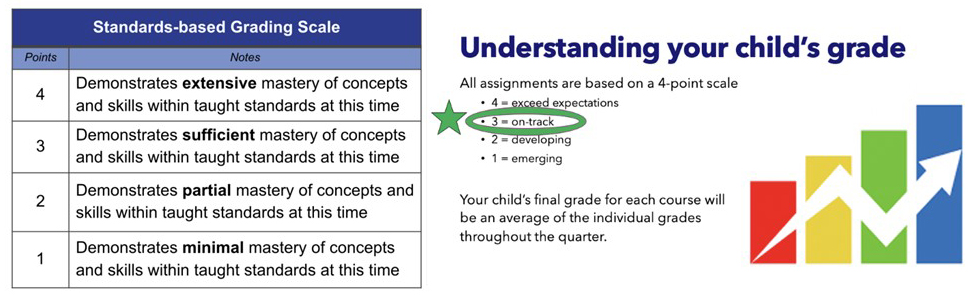

In Monterey’s version of standards-based grading, low grades or missing assignments aren’t held against students if they can prove they have mastered the material at the semester’s end. Instead of the traditional 100-point grading scale, there’s a 4-point grading scale, and students have chances to make up missed assignments or even redo a test. This puts the emphasis where it belongs, on learning rather than on rule-following, says the Monterey Bay Teachers Association member.

Monterey Peninsula Unified School District’s 4-point grading scale and an explanation for parents.

“Under the old system, a student has a zero from not turning in an assignment, then turns in the next one and gets 100,” says Pereira. “Even though he understands the material, he has only earned 50 points, which is an F in the class. Our new system motivates kids to not give up and keep trying, instead of putting their heads on the desk and not caring. For me, it boils down to how students can show me what they know — even if they need multiple opportunities.”

Rethinking how to grade

While a number of educators have been vocal in support of a traditional grading system, many districts have opted to change it. Some, like Monterey, began this journey before COVID-19. Others found the pandemic to be a perfect opportunity to reform grading, with students facing increased academic struggles, stress, depression and challenges at home.

Los Angeles Unified has directed educators to grade students on what they have learned and not penalize them for behavior or missed deadlines. Teachers have been encouraged to give students the opportunities to retake tests, update essays, and demonstrate they understand the material. Santa Ana Unified, Oakland Unified and other districts have considered whether to limit the use of D’s and replace F’s with “incompletes,” according to news reports. And Lindsay Unified School District in the Central Valley assigns students to classes and projects based on what they know and not their grade level — with a 1-4 grading scale designed to foster a “growth mindset.”

The reasoning behind grade reform is that students living in poverty, who are more likely to be students of color, have more challenges. They may be working to support their family, caring for siblings, or even homeless. Penalizing them for turning in late assignments or their behavior creates bias against students and may even unwittingly promote racism, say proponents.

“Our traditional grading practices have always harmed our traditionally underserved students,” said former teacher Joe Feldman, author of Grading for Equity and a consultant with districts nationwide on grading reform, in a Los Angeles Times interview. “Now, because the number of students being harmed is so much greater, people are ready to tackle this issue.”

“Some may say this doesn’t prepare students for the real world, but it does. In the real world you get second chances. You can retake your driver’s license, the SATs and the bar exam.”

—Joshua Moreno, Alhambra Teachers Association

Alhambra: Points go by the wayside

Joshua Moreno, an English teacher at Alhambra High School, did away with points entirely because some students fell so far behind, they stopped trying. Others had so many points they stopped working, knowing they would still receive an A.

Joshua Moreno

“I went into teaching so students could learn and not chase points,” says the Alhambra Teachers Association member. “It’s nobody’s fault. It’s been part of the system since the turn of the century. But now it’s outdated. The 100-point system is really 50 ways to fail. What we call ‘equitable grading’ is part of a larger district initiative led by our new Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Task Force.”

For examples of how traditional grading can go wrong, he created a profile of Student A, who has turned in every assignment on time, is never tardy and writes in a mediocre manner. Then there’s Student B who writes in an exemplary style but is frequently tardy and doesn’t turn in every assignment, which may be due to work, family obligations or other challenges.

“Under the old system, student B would have a C or be failing, and student A might have an A in the class. But it’s time to look at the skills and not penalize Student B for other factors, some of which may be beyond his control. For student A, the point system is masking skills he’s deficient in.”

Moreno gives students second chances to submit work and retake tests. He considers homework “practice” without grading it painstakingly.

“Some may say this doesn’t prepare students for the real world, but it does. In the real world you get second chances. You can retake your driver’s license, the SATs and the bar exam.”

He will even retroactively change a first-semester grade if a student does well by the end of the second semester. “What matters is that they get there — not how long it took.”

“I don’t allow retakes on tests. I don’t think it prepares students for the real world or college. I still use the 100-point system. To me, points demonstrate mastery.”

—Julia Knoff, San Diego Education Association

San Diego: Reform is controversial

When San Diego Unified updated its grading policy in 2020, allowing students to turn in late work and resubmit assignments, not everyone was happy. Some educators were upset that it happened during a pandemic, when things were most challenging.

Teachers worried that grading policies would be dictated by the school board or administrators. They filed a grievance and eventually reached a settlement giving teachers the right to determine:

- The length of the grace period for each late assignment.

- Which assignments may be submitted within the grace period for late work.

- How many times an assignment can be resubmitted.

Meanwhile, the district is implementing standards-based grading at the secondary level, with San Diego Education Association (SDEA) and district talks continuing, to ensure teachers retain their right to grade as they see fit, as granted in the state Education Code. Because behavior is not supposed to affect a student’s academic grade, it is now reflected in a separate citizenship grade.

Under the settlement, teachers don’t have to give students more than one retake or redo per semester, and late work can be submitted without demerits only up to a point.

Julia Knoff

“We had to set boundaries,” says Julia Knoff, an economics and U.S. government teacher at Scripps Ranch High School, who was on the SDEA team that negotiated the settlement. “I understood lenient grading when kids were doing distance or hybrid learning. But now we are back at school. I don’t allow retakes on tests. I don’t think it prepares students for the real world or college. And I still use the 100-point system. To me, points demonstrate mastery.”

Knoff, a teacher for 30 years, fears assignment retakes cause an increased workload for educators, who must regrade assignments. And while some school districts are considering eliminating D’s, she believes that is a mistake. A D is passing and still allows students who are not bound for a four-year college to graduate.

“If you have a kid who never does homework and aces every test and knows the material but fails, the system isn’t working. Now my thinking is: If you learned it, you learned it.”

—Shana Just, Sacramento City Teachers Association

Sacramento: A unique approach

This year, Sacramento City Unified School District adopted a policy that students are not supposed to score lower than 50 percent — even if they don’t do the work — in a move toward eventually phasing out D’s and F’s. The goal is for students to keep trying and redo work so they won’t be derailed from a four-year college.

At Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, some members of the Sacramento City Teachers Association are also changing how they grade students.

Kara Synhorst

Kara Synhorst, an English teacher for high-achieving International Baccalaureate students, has implemented what she calls “labor-based grading” so that strong effort is reflected in students’ grades.

“Grading students for how hard they work is a way to accurately determine what they know,” she says. “I give students weekly assignments, and if they put time and effort into it, they get 100 percent. But I also tell students to put a cap on it, because some high-achieving kids will work all night, and I want them to achieve a work-life balance.”

Since the pandemic, Synhorst allows students to demonstrate knowledge creatively. “They can write an essay, perform an interpretive dance, create a TikTok video, perform a skit or create podcasts. One student demonstrated what she knew through embroidery in the Hmong tradition. I have guidelines: Others must view what they are doing and understand what they are saying.”

She allows a week’s grace period on assignments, during which they can earn full credit. If they don’t turn in assignments until the end of the semester, they receive 80 percent instead of a zero.

“I disagree with those who say it doesn’t work like that in the real world,” she says. “I spent time working in the real world, and if I had a report due Thursday and needed to turn it in on Friday, the boss was OK with that. The real world isn’t robotic. The real world has empathetic human beings.”

Shana Just

Shana Just, who teaches biology at Burbank High, also allows late work without penalty. She has implemented a 5-point rubric for grading. Other science teachers have joined her.

Years ago, after attending a Linked Learning conference in Berkeley, Just began questioning whether the 100-point grading scale was valid. For example, there is a 10-point difference between an A, B and C, and 50 points between a D and an F.

“If you have a kid who never does homework and aces every test and knows the material but fails, the system isn’t working. Now my thinking is: If you learned it, you learned it.”

She puts less emphasis on homework or “busywork” with multiple-choice questions, and instead asks students to explain scientific concepts.

“I tell students, ‘It’s never too late to pass if you can show you understand the concepts — even without the scientific vocabulary. You’re never so far behind you can’t catch up.’ ”

She is pleased students are now more willing to take risks, rather than find the “right” answer. She believes this is the best way to approach science and make new discoveries.

“I’m more flexible about late work, as long as students communicate with me.”

—Jackie Boboye, Chaffey College Faculty Association

Chaffey College: Professor shows flexibility

Jackie Boboye, a counselor and professor at Chaffey College, has changed how she grades students in her Essential Student Success class and her Career and Life Planning course. Since she is preparing students for the future, she wants them to be inspired and excited about learning, instead of devastated by setbacks.

Jackie Boboye

The pandemic brought it all home: Her students are caring for loved ones and are sometimes sick themselves. They have housing and internet problems and are super stressed.

“In the past, students had to provide documentation for late work if there was sickness or a death in the family,” says the Chaffey College Faculty Association member. “With the pandemic, that has changed. I’m more flexible about late work, as long as students communicate with me.”

She doesn’t assign many tests or quizzes anymore. Instead, she’ll ask students to read a chapter and create their own quiz and answer their own questions — or create a summary.

“I want students to be more engaged and be able to express what they have learned. They can’t redo assignments. But I offer them extra credit by taking workshops online, and participating in conferences, which allows them to demonstrate research and learning tying into their career goals.”

Grades are important, but learning is even more important, she believes.

“I love to see them succeed, and then come back and share their success stories with other students. It’s why I love what I do.”

“This kind of change is touchy for teachers. We have a lot of autonomy for grading, but very little training in how to do it. We fall back on the practices of when we were in school.”

—Courtney Konopacky, San Ramon Valley Education Association

Alamo: Change takes time and reflection

Courtney Konopacky

Courtney Konopacky, a teacher on special assignment and an English and history teacher at Stone Valley Middle School in Alamo, began rethinking the grading process when she and four colleagues heard education expert Rick Wormeli speak on standards-based grading. It sparked a grassroots teacher-led movement at her site.

“There was also a lot of resistance,” admits the San Ramon Valley Education Association member. “This kind of change is touchy for teachers. We have a lot of autonomy for grading, but very little training in how to do it. We fall back on the practices of when we were in school.”

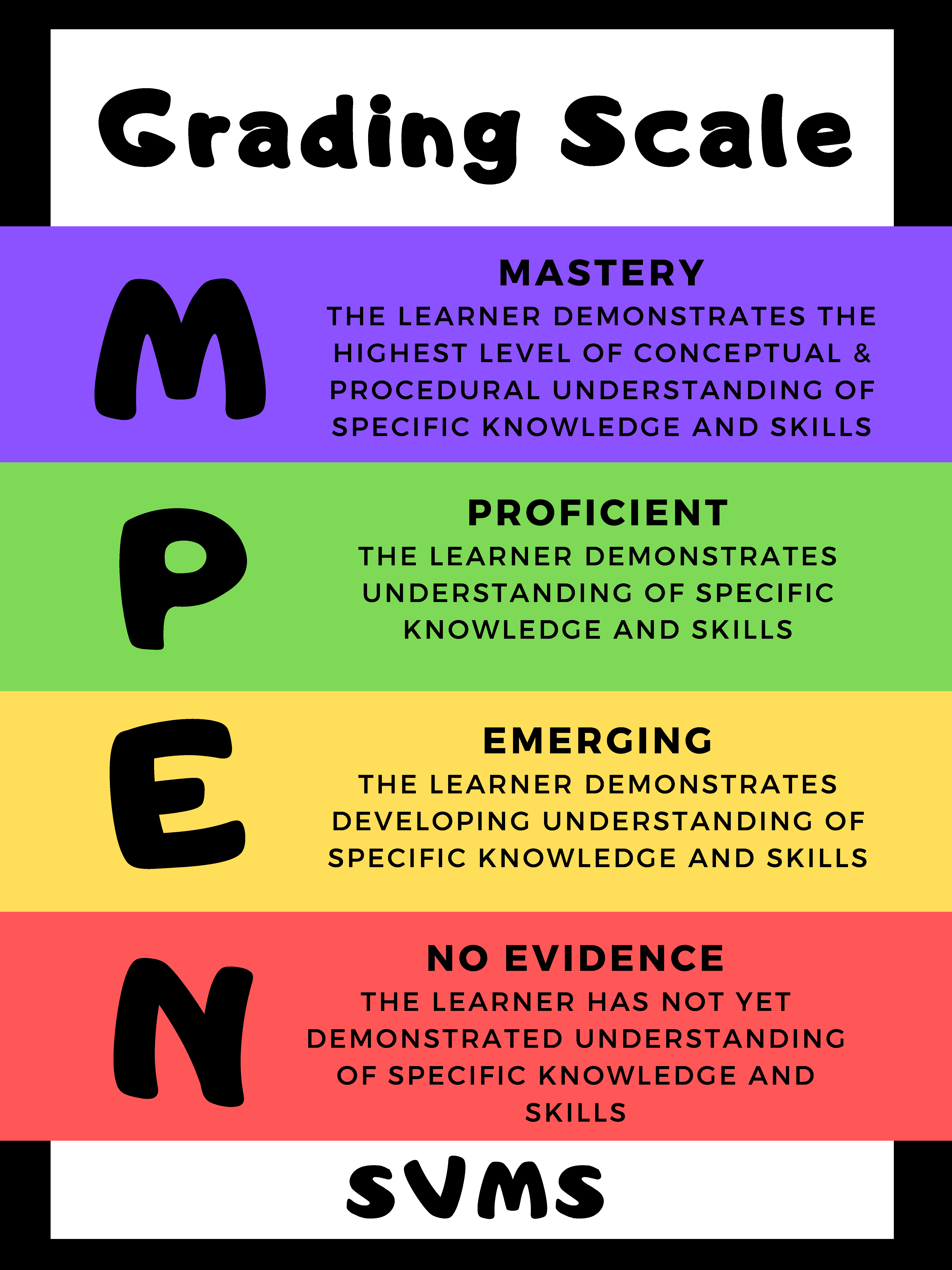

Courtney Konopacky says the transition at her school site from traditional grading to “evidence-based learning” is a work in progress.

She describes the transition as a work in progress with plenty of trial and error and teacher reflection. Her school calls it “evidence-based learning” with a four-point scale of M for mastery, P for proficient, E for emerging, and N for no evidence.

“I understand that at the middle school level, you want to teach functional skills like turning things in on time, good handwriting and following directions. But that can cloud how students are graded — especially boys.”

Some students whose grades were inflated by good behavior received lower grades under the new system, and some parents at the high-performing school were not happy. Teachers had to explain compliance and nice handwriting don’t merit an A.

Last year, a majority of teachers including Konopacky eliminated D’s, but it wasn’t a schoolwide policy. Students can now turn in assignments late and redo work. Konopacky is doing her best to make sure nobody fails, helping students at lunchtime. If a student asks to redo a test or assignment, she asks them to reflect on why they did poorly before and why they think they can do better now.

“It’s a slow process that requires collaboration, vulnerability, and talking about what works and what doesn’t, so we can get kids back on track. Some of us felt guilty about the way we used to do things. But it’s important to look forward — not backward. And teachers definitely need more professional development to help us with this.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment