Educators provide civic guidance as election approaches

Liz Tanner says the current political climate adds an ‘air of the absurd..’

If I didn’t teach government, I would not talk about the election in my classroom,” laughs Liz Tanner, a 22-year government educator and member of Campbell High School Teachers Association.

It’s clear she’s joking, but the sentiment is real. The current polarized political climate has left many avoiding the 2020 presidential election entirely. But with only 55 percent of eligible voters casting ballots in the 2016 presidential election and an increasingly disconnected electorate, many educators are doubling down on why our civic processes are so important.

“I consider my government class more of a civics class,” says Jayson Chang, Santa Teresa High School government teacher and East Side Teachers Association member. “I can talk about how a bill becomes law, but students are so disconnected from that. So instead, we talk about what they can do to change something.”

“ Getting to the why question is so much more important than the what. Help students understand the why to support the what.”

— Travis Humble Perris Elementary Teachers Association

Jayson Chang

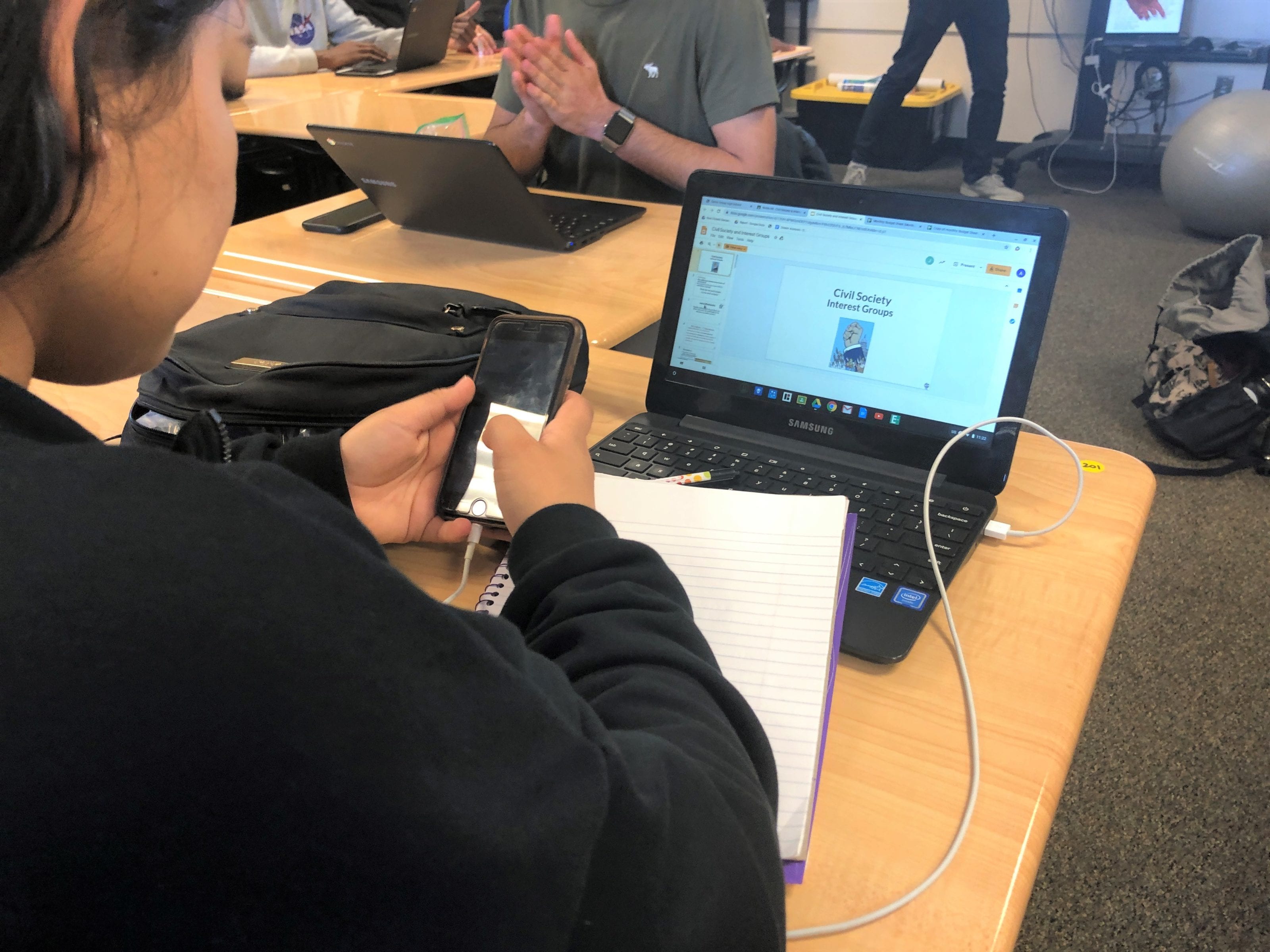

Chang is one of many social studies educators statewide engaging young people about the structure of our government and how to navigate the political process to effect change. In the Digital Era, this civic guidance is even more critical, as young people are ill-equipped to deal with the world of “fake news” when left to their own devices. A recent Stanford History Education Group study saw more than 90 percent of high school students fail miserably in evaluating news sources on the internet, reinforcing that there is still much work to be done in civic education.

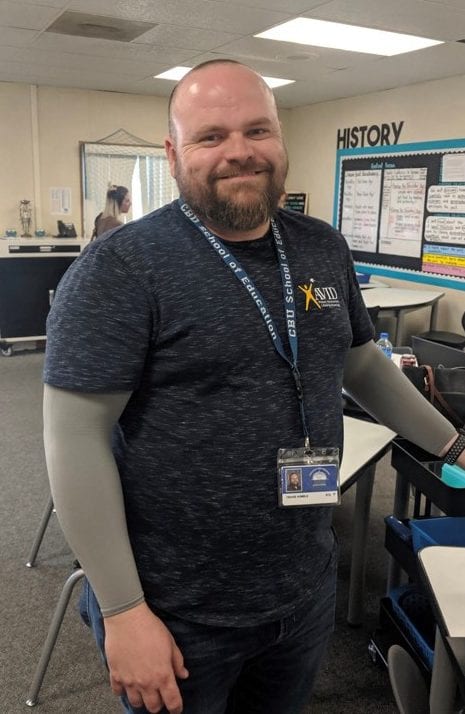

“Kids are frustrated because they can’t discern fact from fiction,” says Travis Humble, seventh and eighth grade history teacher and member of Perris Elementary Teachers Association. “This material affects their everyday life and they’re interested in it, and we need to support them.”

“ Look at the issues, not the person. All sides should be heard. My goal in the classroom is to teach students how to think, not what to think.”

— Jayson Chang, East Side Teachers Association

What Does Good Civic Education Look Like?

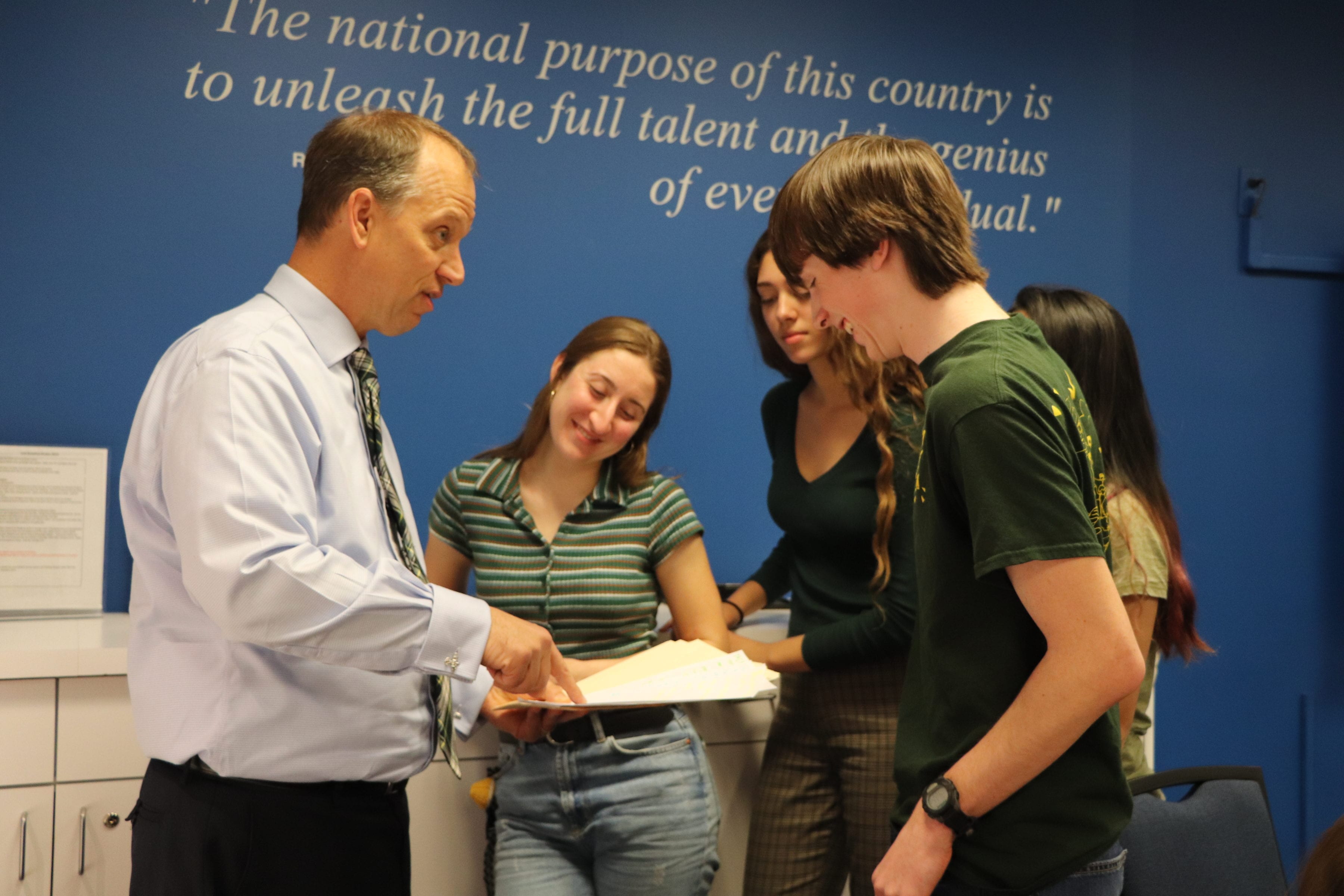

John Downey helps students learn democracy by letting them lead.

The Ronald Reagan Citizens Scholar Institute is a collaboration between Royal High School in Simi Valley and the nearby Ronald Reagan Foundation and Presidential Library that seeks to improve civic education for young people in the community. U.S. government teacher John Downey is an adviser at the nationally recognized institute, which builds civic knowledge and political engagement skills with unique, meaningful learning experiences.

“Students are better prepared to be good citizens — not just able to recite facts about how government works — and they’re doing things in their communities,” says Downey, a member of Simi Educators Association. “Students are leaving here engaged and ready to participate. I think that we’re doing democracy rather than just teaching it.”

Royal High students have regular audiences with candidates at every level of government, asking tough questions about controversial issues and learning firsthand about civic engagement. On one winter day, a local candidate for Congress gave a stump speech, while another event saw a candidate for sheriff field pointed questions about recidivism.

“It’s fun to be able to watch both students and candidates deal with that tension of asking difficult questions and answering them,” Downey says, noting that in-person interactions with candidates and leaders provide a powerful context for students. “We had a person who was running for city council, and she came in reeking of cigarette smoke, and that had a major impact on students.” (These meetings are now being held virtually; for details on how the Citizen Scholars Institute will continue to operate during the pandemic.)

Helping students to see how elections and politics impact their lives directly is a big part of the civic education process. As Chang leads his students through the complex world of political action committees (PACs), voting rights and the role of the media, he wants to give them the tools to be brave and responsible citizens — especially as some of them will be voting in this November’s presidential election for the first time.

“A good chunk of my class is focused on the media because so much of our views are based on the media we consume,” he says. “They need help sifting through the bias so they can make an informed decision on their own.”

Empowering student voices is a crucial part of civics, Chang says.

Chang has his students complete a media bias project to help them be more critical of the information available online and identify erroneous and misleading stories, so they’re able to focus on issues that matter this election and beyond. It’s even more important since many have a soundbite mentality toward current events, getting much of their information from headlines and social media. Tanner says this becomes apparent in the way her government students approach national politics as fodder for biting memes as much as for online petitions and social action.

“There’s an air of the absurd. Everything is a joke,” she says.

Election 2020: Issues Over Candidates

Giving students the tools to navigate news online is key.

Tanner says the presidential election was already garnering attention earlier this year when President Trump’s impeachment proceedings piqued her students’ interest to the point that they watched the live stream of the vote from the floor of the U.S. Senate. Rather than get caught up in the personalities, Tanner tries to focus her students on the political philosophies and ideologies at play, and how they impact how people see the world and think our country should be run.

“We talk about how everyone thinks they’re right when it comes to politics,” Tanner says. “But why do they think this way?”

Humble’s middle schoolers understand the 2016 presidential election’s importance and are already developing their opinions about this year’s candidates. They understand that Americans have a history of not exercising their right to vote, he says, and are eager to be active participants in the electoral process — although sometimes that’s a bit daunting for early teens.

“I tell them, ‘In four years, you’re going to be able to vote,’ and their eyes get so wide,” Humble says. “It’s pretty cool to see them taking responsibility and tackling big issues on their own.”

Andrew Shrock

While much of the attention is placed on the candidates, the issues are really what move young people to get passionate about politics, according to U.S. government teacher Andrew Shrock. The Simi Valley High School teacher says that while students get caught up in the horse race of the presidential election, critical issues like climate change are far more compelling than some old politicians.

“When we first started talking about the election, it surprised me that a lot of my students didn’t know any of the names of the candidates,” says Shrock, a member of Simi Educators Association.

For Tanner’s students, some of the most controversial truths are also familiar ones. For example, when the 22-year female history teacher says, “Politics are a man’s world,” the outrage her students express upon learning that the United States has never had a female president is palpable. Tanner explores why this disparity exists, reading with her students a piece by cognitive linguist George Lakoff on gender roles and political ideology.

“ It always surprises me how heated the conversation becomes when we talk about why we haven’t had a woman president.”

— Liz Tanner, Campbell High School Teachers Association

“It always surprises me how heated the conversation becomes when we talk about why we haven’t had a woman president,” says Tanner.

Teach, Don’t Preach

Teaching about politics, government and elections has always been tricky, but the current political climate has made it even more important for these educators to discuss the issues without including their own opinions. Humble says he tries to approach discussions with deliberate open-mindedness, facilitating discussion without making his thoughts the centerpiece.

“My students don’t know my political standpoint,” Humble says. “My goal is not to get them to follow my way of thinking — I want them to follow their hearts. My goal is to teach, not to preach.”

“My students don’t know my political standpoint,” Humble says. “My goal is not to get them to follow my way of thinking — I want them to follow their hearts. My goal is to teach, not to preach.”

Chang strives to provide a safe space for his students to express their opinions and examine controversial issues that they might not otherwise have a chance to discuss.

“All sides should be heard,” he says. “My goal in the classroom is to teach students how to think, not what to think.”

The ultimate goal, Shrock says, is giving students the tools they need to be good citizens and understand how the system works, and inspiring them to be brave to use their voices to make change.

“I want them to go on to vote and be good members of their communities,” he says. “I want them to understand there’s a process to make change in their community. And I believe in it.”

- Classroom instruction in government, history, economics, law and democracy.

- Discussion of current events and controversial issues, particularly those that young people view as important to their lives.

- Service-learning programs that provide students with the opportunity to apply what they learn through performing community service that is linked to the formal curriculum and classroom instruction.

- Extracurricular activities that offer opportunities for young people to get involved in their schools or communities outside of the classroom.

- School governance participation opportunities for all students.

- Simulations of democratic processes for students to experience and learn from.

Source: Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools by the Annenberg Institute at the University of Pennsylvania

John Downey won’t let a pandemic stop his work as a civics educator and adviser at the Ronald Reagan Citizens Scholar Institute. The institute, a collaboration between Royal High School and the Ronald Reagan Foundation and Presidential Library, continues to offer students virtual opportunities to come together to discuss current events and relevant topics in politics and government.

“We feel strongly that our Citizens Scholar Institute needs to operate as close to normal as possible, for the sake of giving students the experience of community,” Downey says.

To that end, he and other educators kept a brown bag lunch speaker series alive during the spring. “The highlight was a student speaker who lost her grandfather to COVID-19 and was able to speak about his very interesting life, her feelings about having to be isolated because of the positive tests of people in her immediate family, and the need for her student peers to be responsible to each other and take the pandemic seriously.”

The series will start up again in the fall — virtually. “Our first speaker will be the newly elected Associated Student Body president giving a ‘State of the ASB’ address,” Downey says. “Invitations to speak will go out to all of the local office seekers.

- PBS Learning Media’s The Election Connection has videos, activities and lesson plans about the history of elections, voting rights and how the presidential election works, including an interactive Electoral College map that allows students to predict their own scenarios. There’s even a youth media challenge for middle and high school students! pbslearningmedia.org/collection/election-collection

- C-SPAN Classroom Campaign 2020 is a comprehensive home for presidential election information and teaching resources, including how the candidates compare on the issues, historical videos, and lesson plans on everything from candidate ads to foreign election interference. sites.google.com/view/c-span-classroom-campaign-2020/lesson-plans

- Gamify the election at iCivics election headquarters, which features election-focused civics games on the race for the White House, the duties and responsibilities of the president, and the fight against “fake news.” This free-with-registration site also features lesson plans, helpful infographics, and online “webquests” to connect civic concepts to the real world. icivics.org/election

Eligible 16- and 17-year-olds may now preregister to vote in California by visiting registertovote.ca.gov. Those who preregister will have their registration become active once they turn 18, the voting age.

Proposition 18 on the November ballot (ACA 4) would authorize an eligible California youth who is 17 and will be at least 18 at the time of the next general election to vote in any primary or special election that occurs before the next general election.