Photos by Scott Buschman

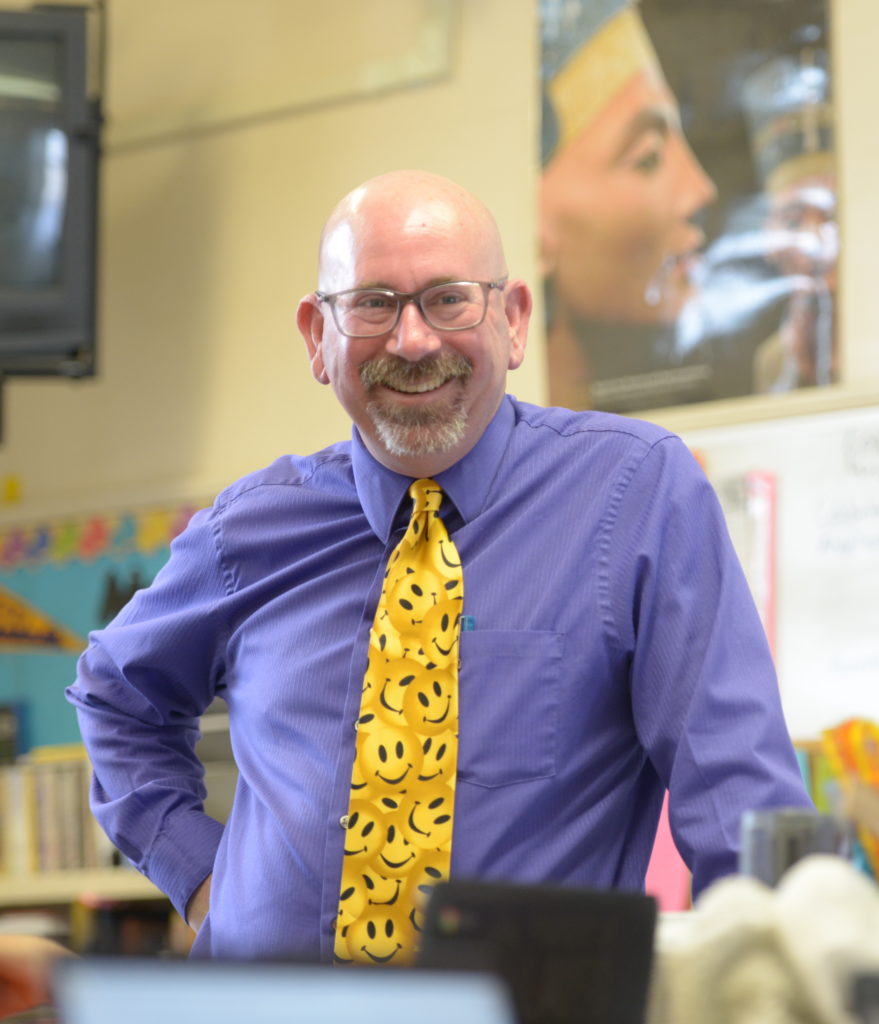

Generation Z: students in Brent Smiley’s class.

They’ve never known a world without the Internet, smartphones and social media. They’d rather text than talk. They don’t care much for books, watching TV or going to the mall with friends. Instead they prefer watching YouTube, streaming Netflix, playing video games and being online.

In their brief lives, they’ve experienced the Great Recession,

terrorist plots, mass shootings and fake news. They’re slow to date or get a

job. Raised during the economic crisis, they worry about the future.

We’re talking about Generation Z, those born between 1995

and 2012 — the students in your class, as well as young adults entering the

workforce or on the brink of doing so. They make up 74 million Americans, or 24

percent of the population.

Don’t be fooled that they’re named for the last letter of

the alphabet. Gen Z (also known as iGen) is at the forefront of tremendous

cultural changes. How can educators best reach and teach Gen Z? What are the

challenges these young people face — socially, emotionally and educationally?

What are the opportunities that they and educators can leverage to help them

communicate and connect with the larger world?

For answers, we look at who Gen Zers are and what they’re experiencing as they grow up today.

This special report is the first of two parts. In part two next issue, we meet Gen Zers who are new educators or about to embark on education careers. We look at what they bring to the profession and how we can support them.

The Challenges

During break, students hang out in Brent Smiley’s classroom at Sherman Oaks Center for Enriched Studies in Los Angeles. Most are on Chromebook computers or looking at their phones.

“We like technology,” says Madisyn Mehlman, 12. “Most of us

have phones. I remember playing on my dad’s smartphone when I was 2, pressing

the buttons.”

About half of the middle schoolers say they are on social

media. Many spend their free time texting and using FaceTime.

Kevin Nguyen, a sixth-grader, says he spends his weekends

playing games online, which he calls “technically hanging out with friends.”

Classmate Juanito Cornejo relies on Snapchat to keep up with what his friends

are doing.

“They are very comfortable in an environment where everyone

can see everything,” says Smiley, a social studies teacher for 30 years and

member of United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA). “They have never known a world

without being watched, being under surveillance in airports and public places

since 9/11 and now online.”

His students don’t grasp the importance of the Fourth

Amendment, which establishes the right to privacy, because they are constantly

sharing their lives on social media.

Unlike baby boomers and Generation X, whose members were

proudly known for caring little about what others thought of them, this

generation cares deeply, says Smiley.

“That’s why bullying and teen suicide is so much higher in

this generation. You can’t be bullied if you don’t care what the bully has to

say. But in this generation, kids live and die based on what others have to

say.”

The reason for the change, he believes, is the Internet.

How much time is too much time online?

A student in Smiley’s classroom, Melania Juga, 12, says she spends a lot of time on Snapchat and Instagram. She likes looking at “influencers” who tell her what is trendy. Like most Gen Zers, she avoids Facebook.

“Sometimes it feels like too much,” she shares. “Sometimes

it feels like being on my phone gets in the way of life and other things I want

to do, like sports and hobbies.”

Jean M. Twenge, psychology professor at San Diego State University, is author of iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy — and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood (2017). The California Faculty Association member, who refers to Gen Z as iGen, interviewed teens and analyzed data from studies involving 11 million Americans from 1967 to the present to enhance understanding of this generation and its impact on our future.

Twenge found that every day high school seniors are spending

an average of 2.5 hours texting, about two hours on the Internet, 1.5 hours on

electronic gaming, and a half hour on video chat. That’s 6.5 hours a day — and

that’s only during their leisure time. Eighth-graders are not far behind at

five hours a day.

Significantly, Twenge found that smartphones have helped

lessen the digital divide. “Disadvantaged teens spent just as much or more time

online as those with more resources. The smartphone era has meant the effective

end of the Internet access gap by social class.”

If teens spend so much time online, what activities are

being left out?

Reading, for one thing. Twenge found teens are much less

likely to read books than their millennial, Gen X and boomer predecessors,

noting that by 2015, one in three high school seniors admitted they had not

read any books for pleasure within the past year, which she finds alarming.

They also sleep less. Teens take their phones to bed, going

online into the wee hours, which makes them drowsier and less able to

concentrate in class.

Also, most iGen’ers spend less time hanging out with

friends, at least in person.

“For iGen’ers, online friendship has replaced offline

friendship,” says Twenge.

Screen time: Risk to well-being?

Twenge finds that teens who spend more time on screen activities are more likely to be unhappy, and those who spend more time on non-screen activities are more likely to be happy. The risk of unhappiness due to social media is highest for younger teens.

Teens are under pressure, says Brenna Rollins, a senior at

Imperial High School near Calexico. “It’s not even about looking good. It’s

about looking perfect and original. If you repeat something — like wearing

something someone else wore or repeating something someone else said — everyone

will let you know and ask why you copied. There’s a lot of judgment.”

Jackson Schonberg, a Redondo Beach High School freshman,

feels less alone when he’s online, and spends about five hours a day playing

games and communicating with friends. Recently he decided to leave his phone upstairs

when he’s studying. But the constant tings of text messages make him wonder

what he’s missing.

“People my age have more depression and anxiety these days,

due to technology,” he says. “Home is no longer a safe place. Even at home, you

can’t get away from stuff that people are saying about you.”

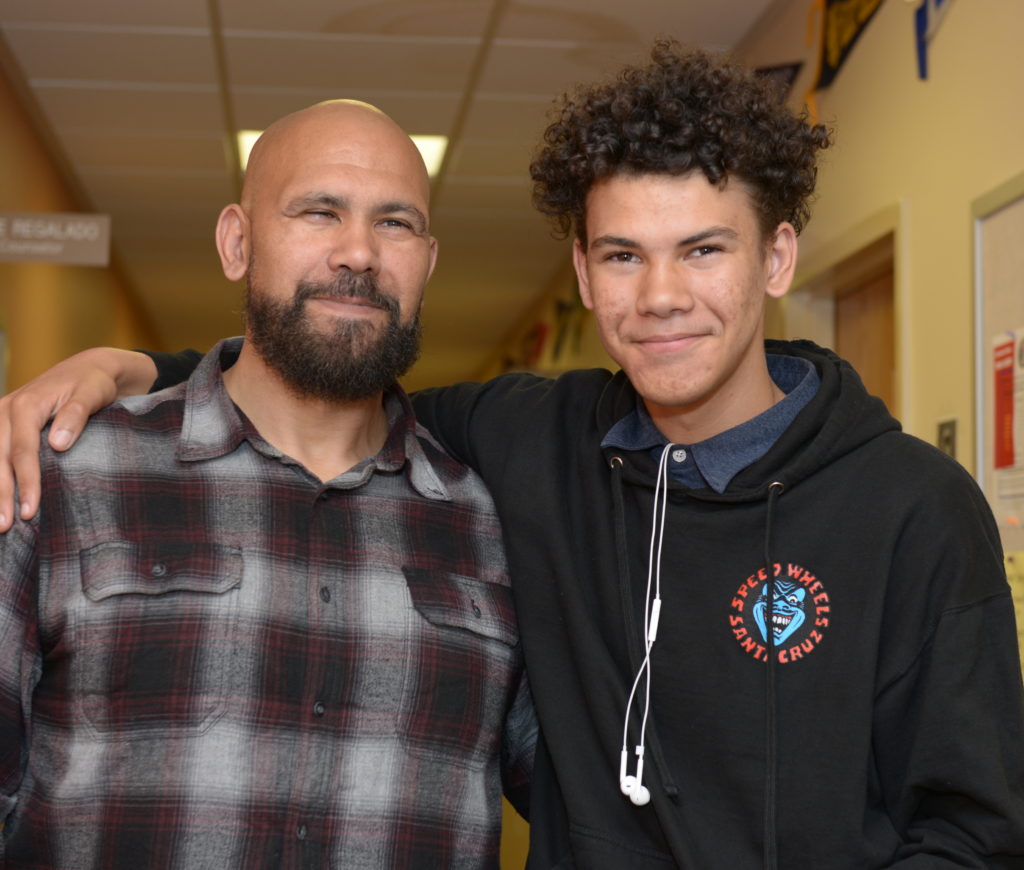

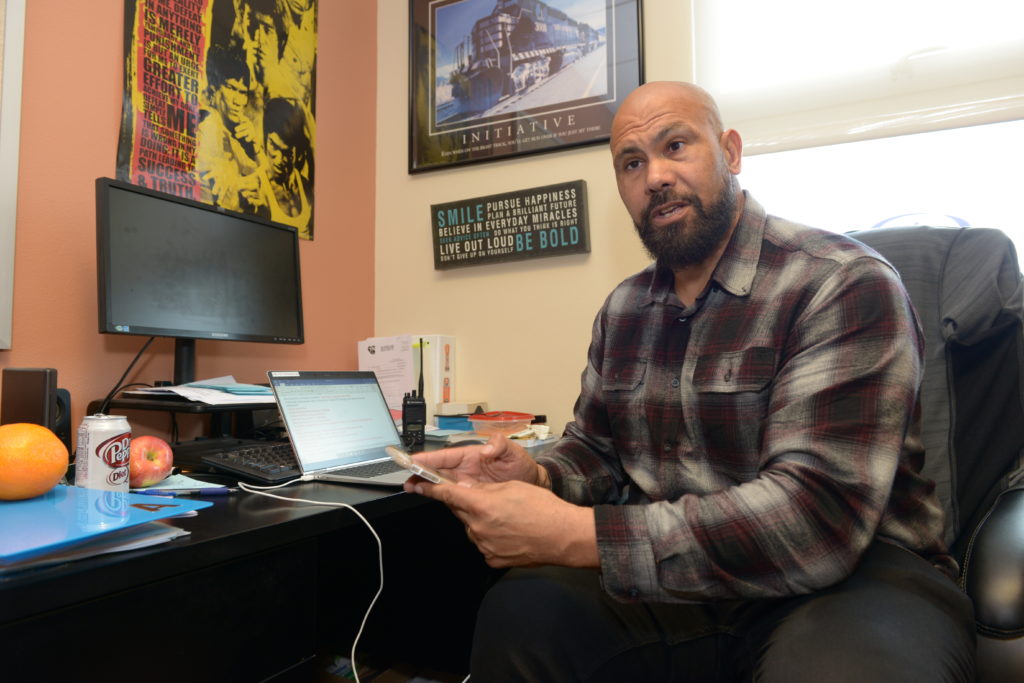

Jackson’s father, Arond Schonberg, a counselor at Redondo

Beach High for 19 years, finds Gen Z teens are much more anxious and depressed

than millennials.

“They have mental health challenges because of their inability

to disconnect from social media,” says the Redondo Beach Teachers Association

member. “They are looking so much for online validation, they don’t take time

to know themselves. Their mistakes, magnified across social media, make the

fear of failure greater. If they don’t get enough likes, they think, ‘I’m not

worthy. Nobody likes me.’ One person may have 1,000 followers, but if a single

person says something negative, they are distraught and think something’s wrong

with them.”

When students come to him in crisis, he offers coping

suggestions. He asks them to remember exceptional times when they succeeded and

thrived. He suggests using social media in positive ways that can inspire

others, such as quotations or a call to action.

Sometimes he will suggest that a stressed-out student “unplug” for a while, which they consider blasphemy. “It’s like telling them not to eat. They say they have to be in the know about what’s going on at all times.”

Twenge says the explosion in digital media use may be linked to the mental health crisis, with skyrocketing levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness and suicide after 2012. She notes that 76 percent more 15- to 19-year-olds killed themselves in 2017 than in 2007, coinciding with widespread ownership of smartphones, increased social media use, and decreased in-person socializing.

“It’s clear we need more funding for counselors in not only

K-12, but colleges,” says Twenge. “Schools are doing a good job of raising

awareness of mental health issues, but they lack the resources needed to deal

with the large numbers of kids having problems.”

Margaret Phillips, a school psychologist for Twin Rivers

Unified School District for 22 years, has noticed a big increase in mental

health issues linked to more time spent online. “It’s tough because once they

put something out there, they can’t take it back.”

The Twin Rivers United Educators member recalls an incident where a student livestreamed videos of her cutting herself. Other students were watching it on campus. Finally, a student told Phillips about it so the student could receive help.

When students are depressed, they seek self-help on the

Internet, she observes. But instead of finding positivity and helpful

suggestions, they may find others who are equally depressed, who — along with

music and videos — encourage self-harm. She tells students to seek out caring

adults instead.

Challenged verbal communicators

But it’s difficult for teens to discuss their emotions. Phillips teaches a social skills class to help students learn to express themselves, which she did not find necessary before texting overtook talking.

More screen time and less in-person interaction raises

concerns that iGen’ers lack social skills, says Twenge, noting that in the next

decade we may see more young people who know the right emoji for a situation,

but not the correct facial expression.

“Because we have grown up with technology and use it so much, we don’t learn to communicate face to face as well,” says Rollins. “Some adults consider members of our generation to be rude and lacking respect. But it’s not an absence of respect, it’s an absence of experience. And it’s hard, because all of a sudden you turn 19 and need to go in front of a panel of five 40-year-olds and know how to communicate well to get jobs.”

The Opportunities

Angie Barton, a millennial UTLA member who teaches at Polytechnic High School in Sun Valley, finds much to admire about Gen Z.

“They are curious and want to learn more,” Barton says. “They are more inclusive, socially conscious, and care about others — even the disenfranchised. They ask good questions. For the most part, they are good kids. They want to be good people and make their families and friends happy, along with themselves. They are extremely creative, and have many interests that they might not otherwise have without technology. Our school has an Animal Lovers Club, a Fashion Club and other interesting clubs, because students were able to connect online and pursue passions that could even lead to careers.”

The biggest strength of Gen Z is open-mindedness, says

Lauren Leiato, a Redondo Beach High sophomore. “We don’t discriminate against

others of different backgrounds or against students who are LGBTQ. Our

generation wants to get rid of hate and be positive and open-minded. We’re more

creative, because we are expressing ourselves and sharing our lives online.”

Jean Twenge says Gen Zers have the tendency to expect

equality, and are often surprised or shocked when they encounter prejudice.

Perhaps it’s because they came of age having a black president and seeing Ellen

DeGeneres on TV.

Gen Z is also the most racially diverse generation to date —

and is the last generation in the U.S. expected to have a white majority.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 49 percent of children under the age of 15

are minorities. By 2020, more than half the children in America will belong to

a nonwhite racial or ethnic group.

In a study by Trendera, 65 percent of Gen Zers said it’s

important to understand people from different backgrounds, 67 percent said that

same-sex marriage should be accepted, and 69 percent said that racism still

exists in the U.S. today.

A cautious generation

Gen Zers are growing up more slowly, says Twenge.

“Today’s youth are waiting longer to date, putting off

getting driver’s licenses, and less likely to work after school or have summer

jobs.”

Teens today spend more time hanging out with their parents,

who often don’t let them walk to and from school or go places alone with

friends. Twenge marvels that instead of rebelling against this, teens have

embraced the need for safety.

Studies show Gen Zers are more cautious. They are fiscally

responsible. They are less likely to engage in binge drinking, heavy partying

and drug abuse. Violent crime and teen homicide are way down. Juvenile

detention centers are emptier statewide; San Francisco even plans to close its

juvenile hall.

The upside, says Twenge, is that teens are safer, getting

into fewer car accidents and less trouble. The downside is that adolescence can

be an extension of childhood rather than the beginning of adulthood. Students

are arriving at college with fewer socializing and decision-making skills,

along with less experience reading books. Adjustment can be difficult. Suicide

is now the second-biggest cause of death for college students, after motor

vehicle accidents.

The need to play it safe translates to academics, say

teachers.

“Emotionally, these kids are very averse to risk and don’t

want to make waves,” says UTLA member Smiley, who worries they might be playing

it too safe. “My greatest fear is they lack a willingness to push back. I worry

that a Generation Z member could find a cure for cancer, and some crochety old

guy in a laboratory will tell them they didn’t follow protocol, and they will

allow their discovery to be dumped out before demanding someone first look at

what’s in the vial.”

The need for safe spaces

In contrast to their millennial counterparts, Gen Z students are more hesitant to speak out in class for fear of saying the wrong thing, says Twenge. Some seek “safe spaces” on campus, which were created by schools for LGBTQ+ students and their allies, students of color, unpopular students, and students with special needs to have a place free of harassment and judgment.

The trend has spread to college campuses, where safe spaces

“protect” Gen Zers from dissenting opinions on both sides of the political

spectrum. UC Berkeley was under pressure to create safe spaces for students

when conservatives Ann Coulter and Milo Yiannopoulos were scheduled to speak,

for example. Twenge notes that viewpoints which would make previous generations

feel “uncomfortable” are now viewed as a threat to iGen’ers’ “emotional

safety.”

She and others think the trend can stifle diversity of

opinion and leave students unprepared for the real world. Proponents

see safe spaces as places where students who might otherwise

feel silenced or threatened can engage in debate and discussion.

Teachers have confided to Twenge that the reluctance of some

students to hear controversial ideas has made them wary of teaching certain

topics, for fear they will be lambasted on social media. (Because they live

online, many iGen’ers who disagree with someone’s beliefs or actions follow

today’s common practice of shaming perceived offenders publicly online.)

Teachers feel compelled to protect students from things that might offend them

by issuing trigger warnings, which let students know about potentially

upsetting material beforehand.

Nascent activists

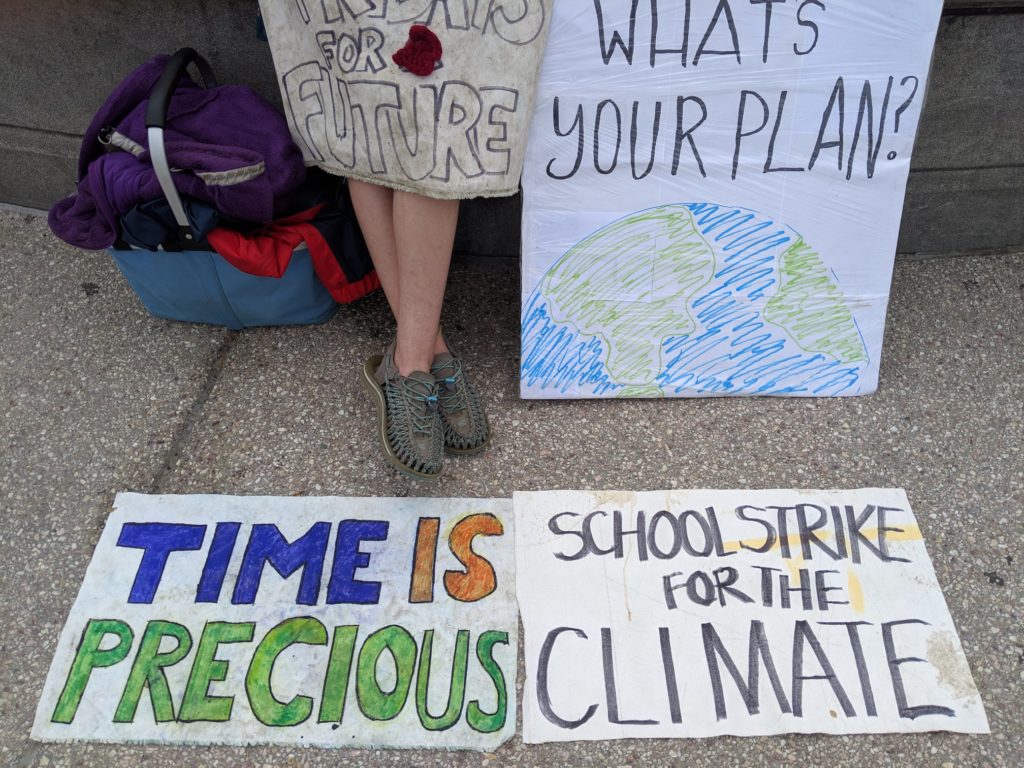

According to recent polling by the Harvard Public Opinion Project, over 70 percent of Gen Zers agree that climate change is a problem, and two-thirds of those think it is “a crisis and demands urgent action.” Many Gen Zers have become activists for climate change, including those in the Sunrise Movement, Zero Hour, Youth for Climate and #FridaysForFuture demonstrations.

Meanwhile, survivors of the 2018 mass shooting at Stoneman

Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, have taken on the NRA and

conservatives to push for gun control. Other Gen Z activists are advocating for

racial equality and equity, earning them the new nickname Generation Woke.

While Gen Z is shaping up to be a very socially engaged

cohort, they largely distrust government, and don’t identify with major

political parties. In a General Social Survey, 54 percent of those ages 18-29

identified as independent, which Twenge says is why many young adults supported

Bernie Sanders and then Donald Trump in 2016.

A new report from the Census Bureau shows 36 percent of

those ages 18-29 voted in November 2018, which is a 79 percent jump from the

2014 midterms. That trend is likely to continue into the 2020 election, and

young people are the most reliably progressive voting bloc, notes Political

Data Inc.

It’s clear that Gen Z “is at the forefront of the enormous

changes under way in the United States today,” says Twenge, driven by the

Internet and other forces of cultural change. “Understanding iGen means

understanding the future — for all of us.”

Josh Miller, a Gen Z blogger for research firm XYZ

University, asserts, “We are a generation filled with social justice warriors,

civic leaders, and changemakers. Past crises and current events shape us.

Digital platforms amplify our messages. Pop culture hero storylines surround

us. Taken together this forms a ‘Heroez’ mentality for many in my generation.

“And like the young adults and teens of the ’60s and early ’70s protesting the Vietnam War and fighting for civil rights, women’s rights and environmental protections, we are going to leave our mark on this world. Just watch.”

Educating a New Cohort

Brent Smiley has a paperless classroom, puts textbooks online, and has students collaborate online.

“After 30 years, I’ve converted to a completely digital

environment,” says Smiley, a social studies teacher at Sherman Oaks Center for

Enriched Studies in Los Angeles and UTLA member. “Yet I haven’t altered my

teaching that much. Technology is just a tool. We need to teach the same things

that have been taught since the time of Socrates: How to think through a

problem, ask a question and find an answer.”

Fellow UTLA member Angie Barton, a teacher at Polytechnic

High School in Sun Valley for six years, incorporates technology into her

classroom with online quizzes and interactive PowerPoints where students can

type notes during her presentation.

“Every day I do something a little different to make it

interesting,” she says.

Barton, a millennial, thought her generation was tech-savvy.

But there’s a big difference, she shares: Millennials prefer computers for

writing, while Gen Z students see computers as antiquated compared to their

phones. Recently a student wrote an entire essay by talking into her smartphone,

and Barton was impressed with the quality of the work.

San Diego State University psychology professor Jean M.

Twenge says teachers have to make it relevant, because Gen Zers “aren’t

convinced that their education will help them get good jobs or give them the

information they will need later.”

So, how can educators engage Gen Z? Below are ideas from a variety of sources.

- Think digital. Post everything from lecture notes to e-books to textbooks online. There are many programs that let educators give assignments, track progress and engage students in an interactive forum.

- Encourage online collaboration. Use Google Classroom, where students can work together from home.

- Personalize their learning. This means adjusting on the fly to see whether challenging concepts need review or should be more fully explored.

- Encourage verbal skills. Have students engage in discussions and listen to different viewpoints. Ask them to discuss how they feel about a specific topic and how it relates to their lives. Ask them to work in groups.

- Publish assignments digitally. Add a layer of motivation and create peer-to-peer learning by publishing their work — essays, video presentations, etc.

- Break it up; make information digestible. Gen Zers have a shorter attention span, are visual, and communicate in memes and emojis. Mix up lectures, discussion, videos, research and presentation. Use charts, graphics and different media.

- Give project-based assignments. Give them a task to do with an end goal and turn them loose.

- Be relevant. Explain why they need to learn what you are teaching and how it applies to the real world.

- Provide instant feedback. Online quizzes with Quizlet and texts with the Remind app and other programs give Gen Zers the instant gratification they need.

- Gamify learning. Minecraft is a great way to teach math. Kahoot! is another game-changer kids love.

- Offer frequent rewards. They are used to winning and going to the next level with video games. Rewards can be points for finishing a project on time or reaching a goal.

Gen Z at the ballot box

Generation Z cast 4.5 million votes, or 4 percent of the total number of votes, in the 2018 midterm elections — a sizable number given that it only counts those who turned 18 after 2014.

Analysis of U.S. Census data by Pew Research Center in May

found that 30 percent of Gen Zers ages 18-21 turned out in the first midterm

election of their adult lives.

In fact, the three younger generations — Gen X, millennials

and Gen Z, or those ages 18-53 in 2018 — cast 62.2 million votes, compared with

60.1 million cast by baby boomers and older generations.

According to the report, Gen Z’s impact will likely be felt more in the 2020 presidential election, when they are projected to be 10 percent of eligible voters. For details, go to pewresearch.org.

Generational Guide

- The Silent Generation: Born between 1928 and 1945 (74-90 years old)

- Baby boomers: Born between 1946 and 1964 (55-73 years old)

- Gen X: Born between 1965 and 1979 (40-54 years old)

- Millennials: Born between 1980 and 1994 (25-39 years old)

- Gen Z/iGen: Born between 1995 and 2012 (7-24 years old)

- Gen Alpha: A return to the first letter of the alphabet for the next generation, born beginning in 2013 and expected to continue until 2025 (the oldest of this group are just 6 years old)

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment