At Student CTA’s Social Justice Symposium in early November, more than 100 aspiring educators collectively recalled some of George Washington’s greatest hits, as taught to them in elementary school. Our first president:

• chopped down a cherry tree;

• had wooden teeth;

• most certainly never told a lie.

Except that never happened.

The chatter comes to a halt when it is revealed that those stories from childhood are not what they seem — Washington didn’t take an axe to a tree, a biographer made up the story about his truth-telling prowess, and as a wealthy white landowner, his mouth was filled with teeth bought from poor people and stolen from slaves.

For many in the group, these revelations are not easy to swallow.

“How do you have the heart to teach kids these lies?” said Lily Dueñas-Sosa, a student from CSU Northridge, asking herself as much as she was the rest of the room. “What do you do?”

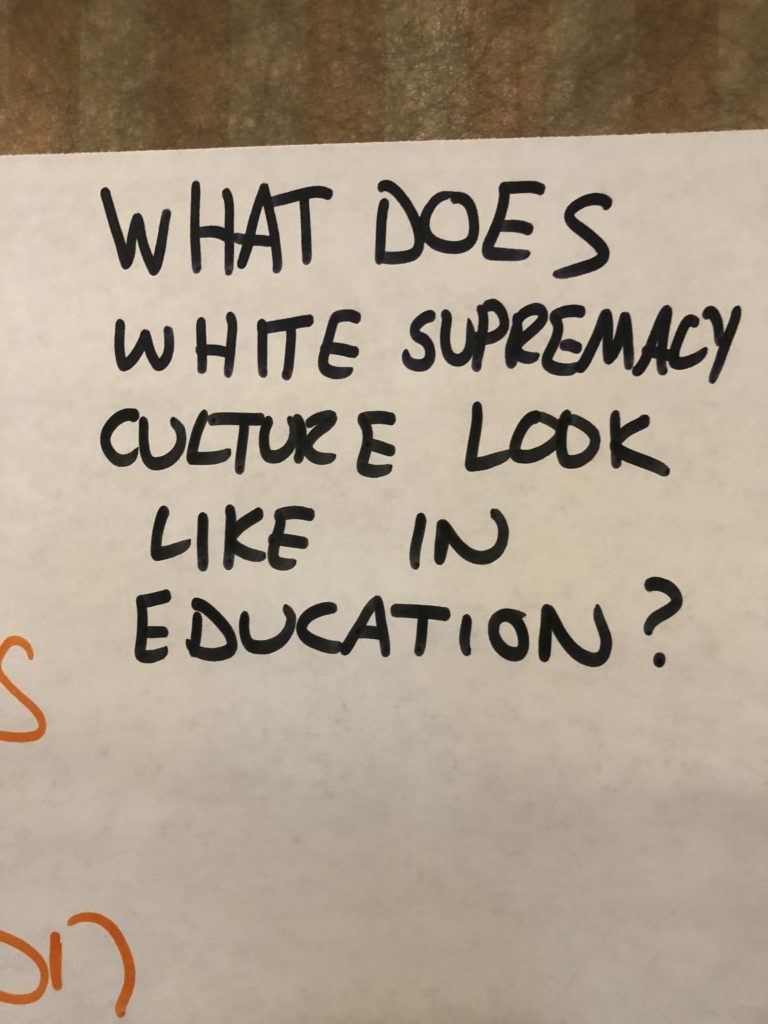

This examination of their own experiences in elementary school is a lens into the pervasiveness of white supremacy culture and its many impacts — a jolting start to a welcoming weekend for future teachers, but it was intended. Brought together from teaching programs at colleges and universities across California, these students aren’t shying away from the SCTA goal that inspired the symposium: “Student CTA will actively advocate for social, political and educational strategies that eradicate institutional racism and white privilege perpetuated by white supremacy culture.”

Is it enough to just teach our students the truth as we know it, or do we teach them how to challenge the system?

Rachel Immerman, NEA Student Chairperson

The symposium encouraged participants to take risks as they explored what for many is difficult subject matter.

“At times, you might feel uncomfortable, but it’s part of the experience we’re embarking on together,” reassured Stavanna Easley, Fresno City College student and Central Regional Vice President of SCTA.

Giving all kids equal opportunity

SCTA’s goal came from a 2018 NEA Representative Assembly resolution that states in part that: “The National Education Association believes that … to achieve racial and social justice, educators must acknowledge the existence of White supremacy culture as a primary root cause of institutional racism, structural racism, and White privilege. Additionally, the association believes that the norms, standards, and organizational structures manifested in White supremacy culture perpetually exploit and oppress people of color and serve as detriments to racial justice.”

“Student CTA is going to be teaching future generations of students, so we need to be aware of these issues,” said Jessica Chamness, a student from Santiago Canyon College.

For aspiring preschool teacher Sarah Ashley Jones, a lot of this is a shock to her comfortable, suburban, white upbringing, but instead of shying away, she’s thinking about how to make sure future students understand racism, inequity and privilege in America. She said the revised history many students are taught in elementary school guides them into a set of beliefs where they subconsciously learn how to feel about themselves, their communities and even the color of their skin.

I feel like if I had learned the truth as a child, I would’ve been braver.

Whitney Anderson, CSU Fullerton student, SCTA Member

“I’m just starting to see that inequality starts so young. I want to see how I, as someone who has white privilege, can work against that and give all kids equal opportunity,” said Jones, a student at San Diego State University. “I don’t want to be ignorant of other people’s experiences.”

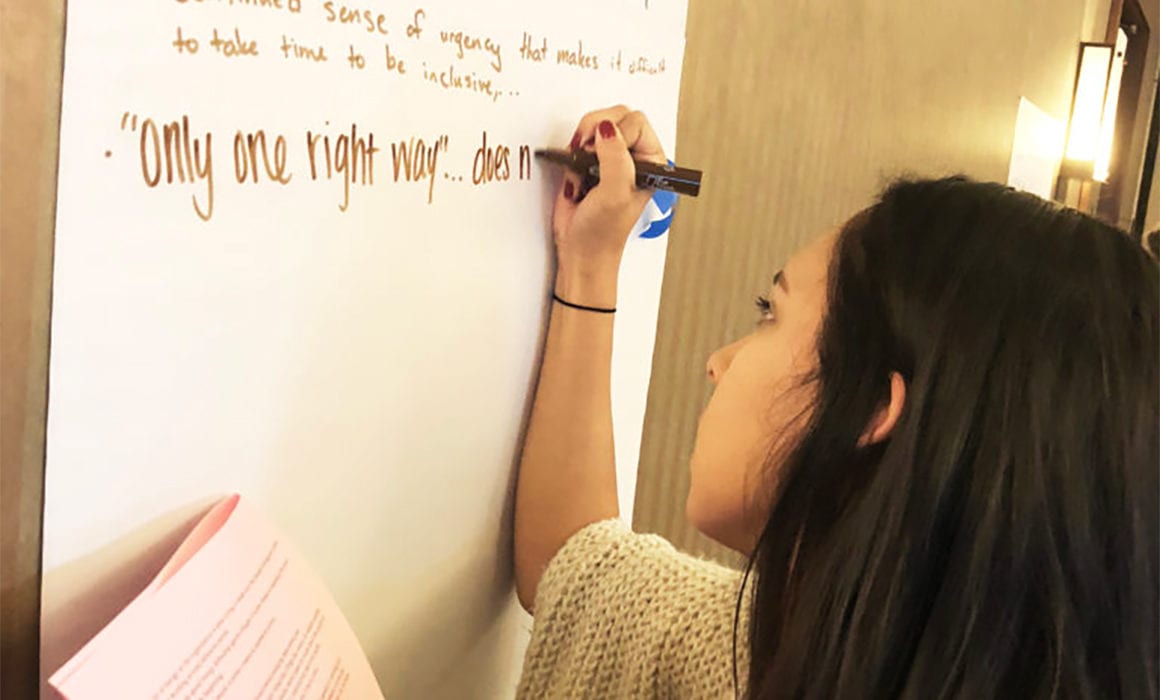

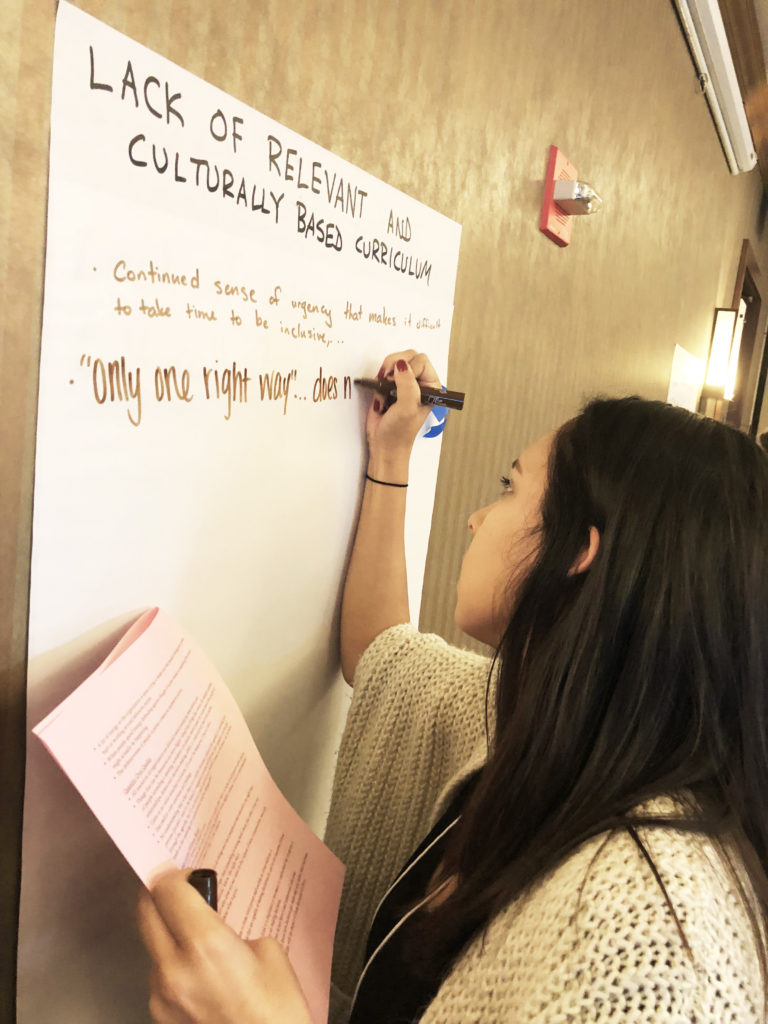

Symposium participants explored these experiences in small-group discussions on the history of white supremacy culture, systemic racism and inequality in the United States, how Americans are socialized to white supremacy culture, and how to build a future that rejects and dismantles a legacy of inequity. Discussions were real and required a lot of raw self-examination.

“We are so naïve and uneducated about so many topics,” said Monserrat Bonilla Flores, a student from Santiago Canyon College. “It made me reflect a lot about what I see and maybe do more of my own research.”

The realization that perhaps the wool was pulled over their eyes about some of the values that built the United States went from shock to disgust to defiance. Whitney Anderson said being confronted with this “real history” in her own schooling would have made an impact on how she looked at the story of America and would have caused her to think more critically about other information she was told.

“I feel like if I had learned the truth as a child, I would’ve been braver,” said Anderson, a student at CSU Fullerton.

The danger of one dominant perspective

Symposium facilitator and CTA Human Rights Consultant Reena Doyle told a story about a friend in school who asked his teachers why Europe was considered a continent when by the definition of the word, it definitely was not. When he finally found one who was willing to answer the question, “because whoever wrote the textbook said it is,” spoke volumes about the power wielded by the people who determine the narrative in history books. What is learned in most classrooms is from one dominant perspective, shaping the beliefs of American children.

This danger of the “single story” silences the voices of others, leading to the labeling of everything as either normal or different, where “normal” is white and “different” is everything else.

“Growing up, normal was always white,” said Siri Peduru, a student from UC Davis. “It’s so important as an educator to break apart that idea of normal versus different and make sure all of our students are treated equally.”

Nearly everyone in the room shook their heads upon hearing the tale of a man named Jose who was having difficulty finding a job, but suddenly had calls for interviews pour in after removing one letter from his résumé: the S in Jose, turning his name into Joe. Again, the reaction went from shock to disgust and then to action, as the students considered what fighting white supremacy culture might look like in their future classrooms.

“We thought we were taught the truth before,” said Rachel Immerman, NEA Student Chairperson. “Is it enough to just teach our students the truth as we know it, or do we teach them how to challenge the system?”

A room full of heads nodded in agreement, as these future educators considered the concerted effort it will take to unteach hundreds of years of white supremacy and systemic inequality. With this awareness of the discrepancy between what’s in books and what actually happened, many of them emerged ready to do their part.

“I’m falling into the same pattern of teaching from the textbook,” said Laura Ensberg, a student from San Diego State University. “I want to know how I can not do that and start teaching my fourth-graders the truth.”

For more information about Student CTA, visit studentcta.org or facebook.com/studentCTA.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment