Long before Gov. Gavin Newsom signed groundbreaking legislation that adds a one-semester ethnic studies (ES) course to high school graduation requirements, Stockton educators were working on making ES curriculum an integral part of students’ education.

The new law — Assembly Bill 101 (Medina) — is especially relevant to Stockton and its students. Stockton was named “the most diverse city in the nation” by USA News last year. It was also described as a city “scarred by its past,” linked to racial tensions and dire economic disparities.

Race and opportunity have been largely intertwined, according to the report, “with the city’s people of color often faring poorly on health and economic measures despite the city becoming majority-nonwhite more than three decades ago.”

Some members of the Stockton Teachers Association (STA) believe that creating a more inclusive curriculum and offering ES courses to all students are a path toward healing and encourage civic engagement and community-based social justice.

Ed Arimboanga Jr.

“ES allows students in Stockton to see themselves in the curriculum and to be proud of their history and culture,” says Ed Arimboanga Jr., a teacher on special assignment (TOSA) overseeing the ES program at Stockton Unified School District. “It also inspires them to want to do something about the many issues and challenges we face in Stockton.”

A necessary component of education

The new legislation mandates that the ES graduation requirement will go into effect in the 2029-30 school year. High schools must begin offering ES courses as an elective by the 2025-26 school year. (See sidebar “The Ethnic Studies Mandate” below.)

Arimboanga and other STA members have made Stockton Unified a trailblazer in ES well before these deadlines. They are making a case to the school board to allocate funding for classes, additional teachers and professional development; are gathering community and student input on what will be studied; and are setting timelines on instructional goals and new course offerings.

Arimboanga and ES teacher Aldrich Sabac are part of the district’s Curriculum Development Team, comprising 12 teachers, two curriculum specialists, and five community members. The team is tasked with charting a future course for ES and filling the subject’s curriculum void. (California’s ES model curriculum offers some resources and lessons, but an entire curriculum is currently not available.)

Ethnic studies is the study of historical and contemporary narratives, contributions, struggles and resistance by people of color and historically marginalized communities. It includes historical and sociological analysis of how colonialism, race and racism have been (and continue to be) powerful social, cultural and political forces.

In some communities ES has been controversial, but in Stockton, ES is considered a necessary component of education.

Aldrich Sabac

Research shows student benefits related to ES, observes Sabac, including improved attendance and grades, higher graduation rates, growth in literacy and critical thinking skills, and the ability to engage in meaningful conversations about race.

“It also brings students together,” he says, noting that ES helps foster respect for different cultures and build community and a sense of interconnectedness.

Positive feedback from students, educators

A 2020 survey of Stockton students enrolled in ES showed 92 percent had developed an increased appreciation for other cultures, 90 percent enjoyed the course, and 85 percent would recommend it to other students.

“Ethnic studies means a lot to me,” says 12th grader Mercedes San Nicolas, a student at Edison High School. “You learn about things you wouldn’t normally learn about in a regular history class.”

“Ethnic studies inspired me because it makes me feel like I have a voice,” says Andrew Sajor, also an Edison 12th grader. “I’m not scared to represent who I am, especially as a Latino and Filipino.”

ES operated as an after-school program in Stockton from 2009 to 2016, primarily focused on Filipino American studies. In 2017, the district adopted a broader ES course description, and classes were held at three schools. During that year, STA members and advocates drafted a district resolution to fund the program, and succeeded in getting a TOSA hired, who happened to be Arimboanga. In 2019, a small group of teachers organized to help get a resolution passed to strengthen and expand the program.

In 2019, the Stockton Unified school board passed a resolution strengthening and expanding the existing ethnic studies program. Student and educator supporters pose right after the vote; Aldrich Sabac is in the front row with glasses, and Ed Arimboanga Jr. is in the back row, second from left.

In addition to the Curriculum Development Team, the district’s ES Community Collaborative is a larger group of stakeholders who contribute their perspectives.

The team continues to seek community input — connecting with elders and community organizations from diverse groups in Stockton, including Black, Native American, Asian, Filipino and Latino residents. The team has also welcomed input from students, parents and college professors. All of these participants have made valuable suggestions for richer content and have increased buy-in for the ES program.

“Community input is a very powerful tool,” says Aldrich. “It makes sure that our curriculum is a reflection of who we are as a community and also influences how we design our professional development.”

Big plans for the ethnic studies program

The team is building on existing ES courses and plans on bringing the new and improved curriculum to the school board in the spring for adoption.

Ethnic studies professional development at Stockton’s Chicano Research Center, summer 2021.

This year’s goals include adopting upper-division specialty ES courses; piloting dual enrollment courses between San Joaquin Delta College and high schools; collaborating with history teachers, ELD instructors and K-8 teachers to integrate ES content into different subjects and grade levels; and piloting an ES educational pathway at Edison High. The pathway, a partnership with Sacramento State University’s educational equity program and Delta College, would be an effort to “grow our own” ES educators, as a presentation on the 2021-22 scope of the district’s ES program put it.

Long-term goals include creating an ES department at the district level that supports K-12 staff and teachers with professional development in culturally relevant and ES-centered pedagogy and content.

“When ethnic studies is incorporated into student reading, writing and ELD skills — and also supporting students with special needs — it becomes super engaging,” says Arimboanga. “Eventually ES will be expanded to include music, art, guest speakers, multimedia, students writing about their own lives, and students going out into their community to create action research projects. Ethnic studies is a big part of wellness and social-emotional learning. We are very excited at what the future will bring.”

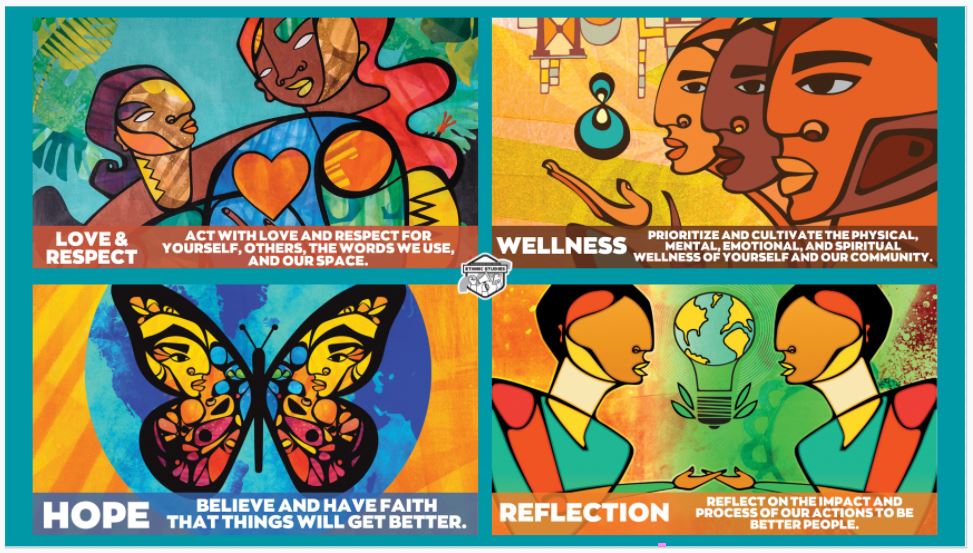

Four of the 10 principles of ethnic studies, part of a presentation on the 2021-22 scope of the ES program at Stockton Unified School District.

The Ethnic Studies Mandate

On Oct. 8, California became the first state to require all students to complete a one-semester course in ethnic studies to graduate. Assembly Bill 101 (Medina) takes effect starting with the graduating class of 2029-30, and high schools are required to offer ES courses starting in the 2025-26 academic year. Many high schools already have such courses, and a few districts have already voted to require students to take ethnic studies. (See sidebar “Ethnic Studies’ Long and Winding Road” below.)

For decades, ES advocates have pushed for a curriculum that more closely reflects the history and culture of California’s diverse population. Earlier legislation authorizing the creation of an ES curriculum stated it should highlight four ethnic and racial groups whose history and stories have been traditionally underrepresented: Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and Asian Americans.

The state’s Instructional Quality Commission, which oversees curriculum development, created a model curriculum that was approved by the State Board of Education in March and is optional for districts to use. It encourages discussion of the ethnic heritage and legacies of students in individual communities. It also includes lesson plans on Arab, Armenian, Jewish and Sikh Americans. Find the curriculum at cde.ca.gov/ci/cr/cf/esmc.asp.

Ethnic Studies’ Long and Winding Road

Ethnic studies (ES) has been taught in some California classrooms for years. The ethnic studies movement famously began in California, where students protested in the late 1960s at San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley to demand courses in African American, Chicano, Asian American and Native American studies.

Efforts to teach ethnic studies to younger students followed. In 1976, the superintendent of public instruction published an analysis of curricula for “ethnic heritage programs” to help teachers incorporate ES in K-12 classrooms. As a February 2021 Education Next article reports, state budget constraints impeded growth of these programs for years.

Activists and educators brought the issue to the fore again in the 2010s. Teacher Jose Lara won a school board seat in the small district of El Rancho Unified, east of Los Angeles, on the promise to deliver ethnic studies as a graduation requirement. In 2014, ERUSD became the first district in California to adopt the requirement.

Lara helped found the Ethnic Studies Now Coalition, which lobbied the LAUSD school board to adopt an ES graduation mandate in 2014. The plan was overruled for financial reasons, and the district instead created a yearlong elective in 2016. Almost a third of the city’s 150 public high schools already offered at least one related elective in fields such as Afro American history, American Indian studies, Asian literature and Mexican American studies.

In San Francisco in 2010, 10 social studies teachers launched a pilot ES curriculum in five high schools, later expanded to all 19 SFUSD high schools. In 2014, Stanford University professor Thomas Dee and a colleague began to study the impact of an ES course on 1,405 SFUSD ninth graders, who were at risk of dropping out and who had been assigned to the course.

The data showed that enrolling in the elective improved general academic performance, measured by attendance, grades and credits earned. A follow-up study, published in 2021, found that the ninth grade ethnic studies class has had a prolonged and strong positive impact on students, increasing their overall engagement in school, probability of graduating, and likelihood of enrolling in college.

The study was cited by Gov. Gavin Newsom in his support for the state’s Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum. School districts, however, are not waiting for the state mandate, but setting their own, including in LA, Fresno and Riverside. And the number of districts offering ES courses has been increasing to reflect California’s demographics and history.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment