Photos by Scott Buschman

Teachers, parents, students and alumni of Marlton School took to the streets twice last spring. The revolt was sparked by the dearth of administrators who are fluent in American Sign Language (ASL) and have experience and training in Deaf Education. Protesters also charged that neglect by Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) has resulted in cuts to extracurricular programs, sports and electives; large class sizes; high staff turnover; and decreased morale in educators and students.

Protesters demanded the departure of the school

principal, because she lacked knowledge and experience in Deaf Education, was

not fluent in ASL, and could not fluently communicate with Deaf students and

staff. The principal has since left, an interim principal is on campus, and a

new principal is slated to be hired next fall.

Educators have reason to hope that the next principal

will be different. The first-of-its-kind LAUSD school principal job description

requires the new hire to be experienced in Deaf Education and fluent in

ASL, instead of meeting requirements for principals at typical hearing schools.

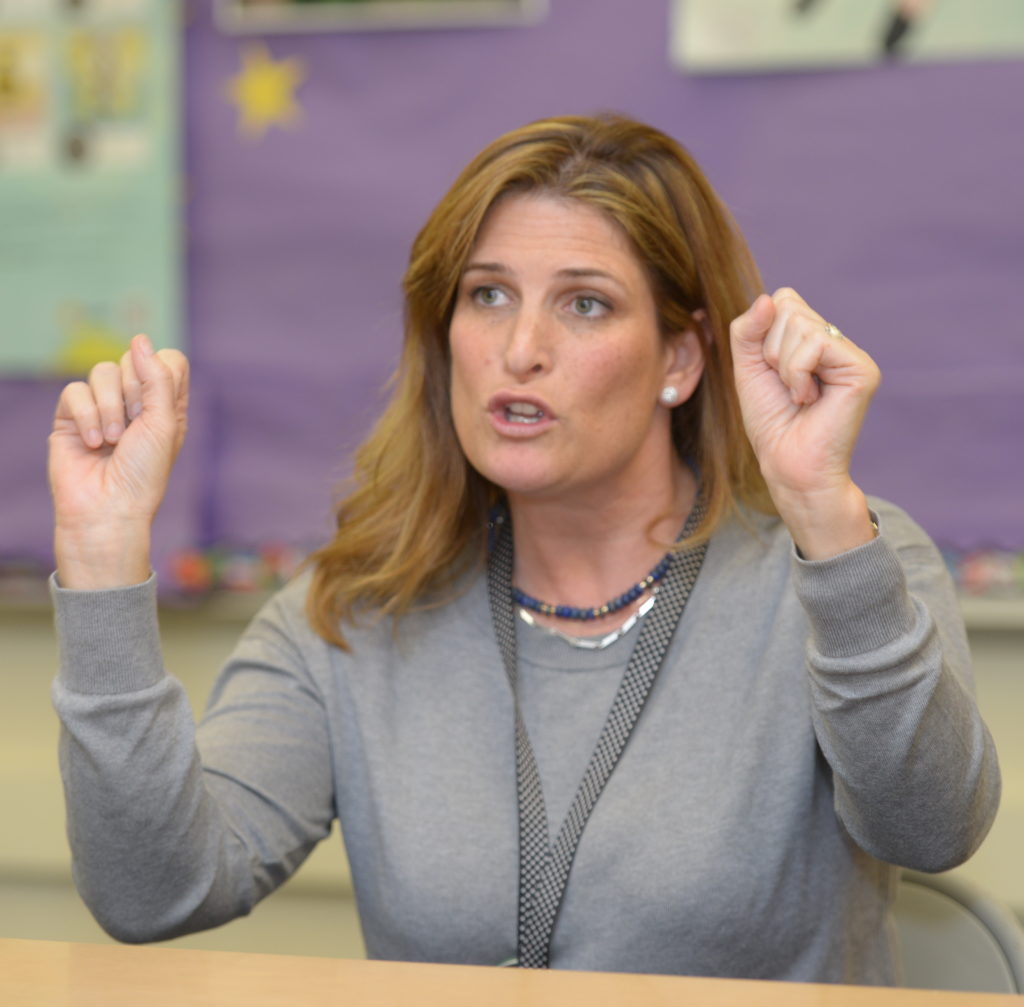

Another positive outcome since the protests is that United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) member Lauren Maucere was hired as the new program specialist for LAUSD. She is Deaf, a former Marlton teacher, and the current president of California Educators of the Deaf. She will work with all ASL-English bilingual programs within the district and has begun visiting classrooms and meeting with staff to help improve outcomes for Deaf students. Her hiring is a groundbreaking move and a step in the right direction, say educators.

“I believe it’s the first time a Deaf person is working

at the district level with the Deaf Education sector, and it’s about time,”

says Maucere. “Deaf people are rooted in their community, which is rich in

heritage, culture, language and connections they bring to the classroom. Deaf

people, especially those trained in Deaf Education, must be a critical part of

the Deaf Ed system, for they have the knowledge, experience and perspective to

ensure a just system that taps into the strengths and abilities in Deaf

children. Deaf children and families need role models.”

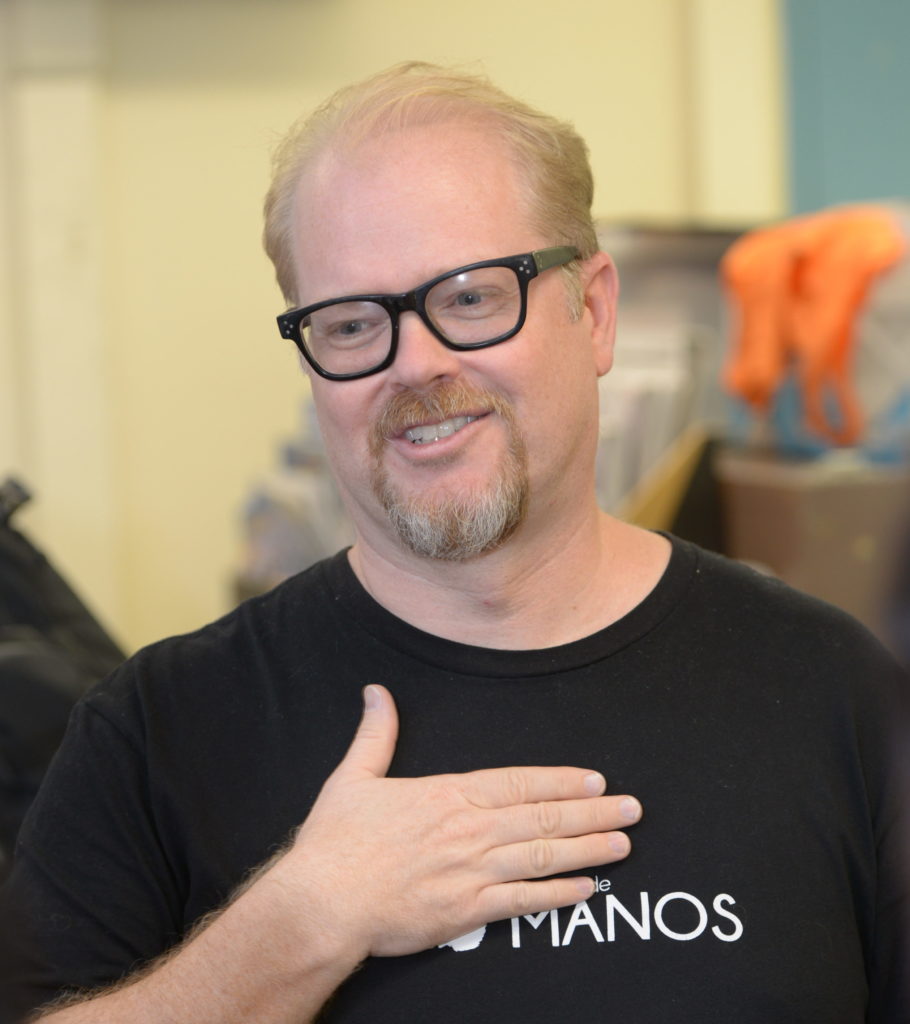

UTLA chapter co-chair Richard Hall is feeling cautiously optimistic these days.

“I believe good things will happen,” says Hall, who is

Deaf and teaches ASL, English, career exploration and filmmaking. “We have had

several meetings with Local District West [the LAUSD office responsible for

overseeing Marlton] and special education leaders. They are interested in

supporting us by providing resources in our search for a permanent principal

with proper qualifications. They also recognize there’s a lack of Deaf

administrators in LAUSD — and there are obstacles that the hiring system

created for the Deaf.”

The protests increased public awareness about a

population that is traditionally underserved, says Hall.

“I was very proud to see the protests happen. It was way

overdue. Educators, students and parents are fed up with how things were

handled. We often weren’t included in decisions made by administrators who were

not familiar with Deaf culture. I am very grateful for the support the school

received from our community.”

A once-prestigious school

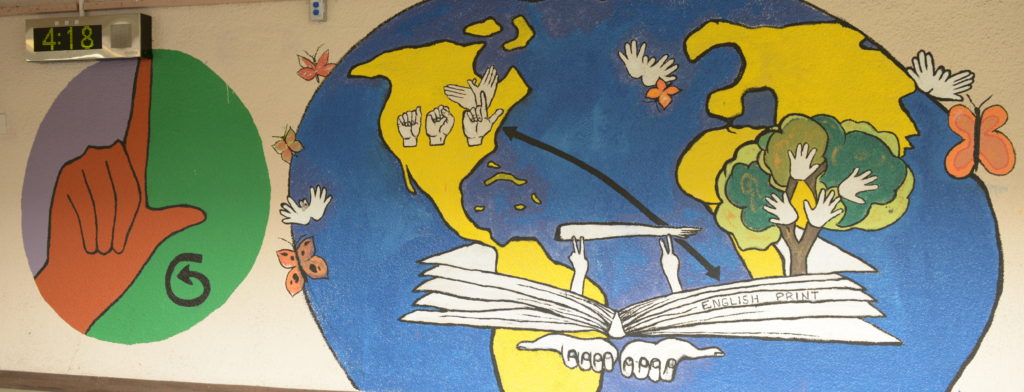

Founded in

1968, Marlton is the only school for Deaf and hard of hearing students run by a

California school district. (Residential schools in Fremont and Riverside are

operated by the state.) Serving students in preschool through 12th grade,

Marlton offers standards-based, college preparatory A-G curriculum. The goal of

the bilingual school is to nurture the development of ASL and English language

literacy skills in Deaf and hard of hearing children.

The school, which currently has about 15 teachers (not counting several long-term substitutes), also has hearing students enrolled in a program for siblings of Deaf students, created by Carol Billone, the first Deaf teacher hired in LAUSD. About 85 percent of the school population is low-income.

Nestled in Baldwin Hills, Marlton is not easily

accessible to many students in LAUSD. Some say its remote location has led to

district neglect and is a factor in why just 135 out of 2,100 Deaf and hard of

hearing students attend school there. Despite a small student population,

Marlton has strong parent supporters. Some drive many miles each day, so their

children can be taught in both ASL and English.

The other Deaf and hard of hearing LAUSD students attend

local schools and rely on interpreters. This mirrors national statistics: More

than 86 percent of Deaf or hard of hearing students in the U.S. are

mainstreamed in public schools. Students spend most of the school day in

general education classrooms with support from an interpreter, according to

“Raising and Educating Deaf Children,” a 2016 report from Oxford University.

Susan Margolin, a Deaf teacher for Marlton’s middle and

high school students, believes students benefit from receiving direct

instruction in ASL.

“Other students may attend regular classes with sign

language interpreters who often do not sign details in full, and students may

miss information as a result of their dependence on inadequate signing,”

Margolin says.

Marlton was created to provide students with an

environment where they could communicate with everyone on staff without an

interpreter present. However, because none of its administrators are fluent in

ASL and the majority of past and current administrators lack a background in

Deaf Education, administrators may resort to pointing, gesturing, or not

communicating with students and staff.

The school has been a revolving door for administrators, with five principals in eight years, not including interim principals. Educators hope new administrators will bring a wealth of best practices in Deaf Education to enrich the academic and linguistic environment, propelling Marlton beyond providing just a basic education.

“The general impression from past administrators has been

that our school needs to be ‘fixed’ and that our Deaf and hard of hearing

population is somehow not as important or lesser than the general education

population,” says Laura Carls, a Marlton preschool and transitional

kindergarten teacher. “In reality, we are all equal. Some of us just use

another language to communicate.”

Years ago, Marlton was considered a state-of-the-art

school that offered extracurricular activities including a wide range of

sports, plus woodshop, culinary arts, art and theater. Funding cuts eliminated

these programs along with most electives.

“It’s sad to see those programs go, because they were

instrumental to our students’ learning and social experiences,” says Hall.

“Participating in sports and community-based instruction — a program designed

for Deaf students from 18 to 22 to be college and career ready — allowed our

students to build self-esteem and become team leaders as well as team players

with their peers. They also learned how to communicate with each other and

other adults.

“With those programs cut, it’s like losing limbs. It

affects school morale. It’s difficult getting students excited when they have

nothing to do after school but go home where they are alone. Many of the

students’ families do not sign, and they feel like strangers among their

families.”

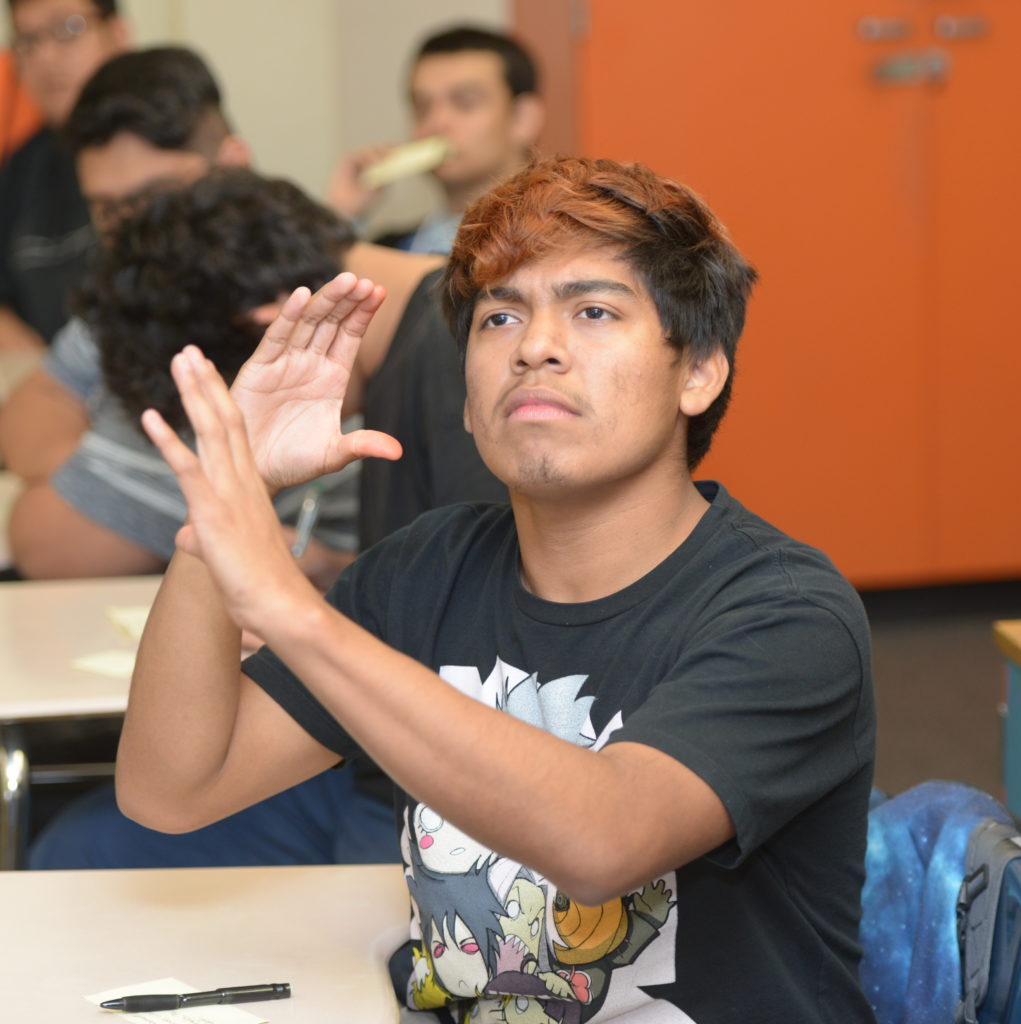

Noe Perez, a Marlton senior and vice president of his class, says that he has noticed the school’s decline since he enrolled as a fifth-grader.

“When I first came here, there was a lot of interaction,”

he signs. “I liked it. I wish there were more things going on for students now

like sports, social events and field trips. Because of these things, the

school’s population has gotten smaller. I think bringing things back like

sports would help Marlton improve and make it a better place.”

As programs dwindled, class sizes increased dramatically.

The California Department of Education recommends a teacher-student ratio for

this population of 1-to-8, but many classes have more than 20 students.

“With small classes of one teacher to eight students, we can prepare students for

graduation and jobs in the larger world,” says Margolin. “As of now, we have

almost all big classes due to LAUSD’s budget issues. Can you imagine that I am

now teaching two courses — Financial Algebra 1 and Financial Algebra 2 — to 23

Deaf students during the same period? It’s not quality time.”

“I feel LAUSD has not concentrated on quality Deaf

Education,” she continues. “This failure impedes opportunities for graduates.

Many students do not reach grade level in math.”

Data from the National Deaf Center on Postsecondary

Outcomes show Deaf people attain lower levels of education than their hearing

peers. In 2015, 83 percent of Deaf adults in the United States had successfully

completed high school, compared to 89 percent of hearing adults. The gap in

educational attainment between Deaf and hearing was the widest, at 15 percent,

among individuals who had earned a bachelor’s degree. This is important because

increasing levels of educational attainment has been shown to narrow the

employment gap between Deaf and hearing individuals. Research shows that only

18 percent of Deaf adults in the United States have a bachelor’s degree or

more, compared to 33 percent of hearing adults.

Everyone agrees that it’s time to close the achievement

gap. However, because Marlton has suffered more than its share of budget cuts

and neglect, staff and students say they feel marginalized and unsupported.

Janette Duran, a Marlton School counselor, says students

face challenges in addition to being Deaf, since most are poor and minorities.

“Given the history of how students of color have been

marginalized in school districts across many generations, with schools and

administrations neglecting students’ multiple social experiences, the hope is

that LAUSD can recognize that this reality is intensified with our Deaf

students, given their multiple intersections.”

A strong sense of community

Despite difficult conditions and low morale, educators are passionate about Marlton, and say working there is extremely rewarding.

“I believe that Marlton has the potential to allow Deaf students to be more successful academically,” says Claire Ettlin, who teaches third- and fourth-graders. “There are enormous benefits to having language exposure everywhere in school. The social aspect of the school alone is an enormous gain for the students as opposed to a mainstream school, where many Deaf children suffer from isolation, which can affect their education regardless of the quality of instruction they may receive.”

Marlton has a great sense of community, she adds. “We are constantly advocating for our population and trying to give them access and opportunity wherever it is possible.”

“Marlton school culture is very close-knit and

nurturing,” says Mallorie Evans, an audiologist at Marlton for 13 years. “Since

many students come from families in which they have little or no communication,

school becomes home to them. It’s a place where they can truly express

themselves and have meaningful relationships with others who are like them.

Students’ attachments are much deeper at Marlton than it is at most schools.”

Maria Hernandez graduated from Marlton in 2009, earned a

bachelor’s degree from CSU Northridge in liberal studies, and works at Marlton

as a paraeducator. She wants to become an elementary teacher at the school.

“I learned so much here,” she says. “This is a place with great teachers. It’s a place where we can teach Deaf students about life and how to become role models.”

Union Strong

During last spring’s protests at Marlton, UTLA officers and professional staff were there in support every step of the way. (UTLA members continue to support their Deaf colleagues with sign language interpreting services at UTLA conferences, meetings and rallies.)

Marlton audiologist Mallorie Evans, who serves on the UTLA Board of Directors, says the Deaf community’s support and union activism forced the district to listen to educators’ concerns.

“UTLA stepped up in a major way when Marlton teachers needed them the most. Even though they didn’t know much about Deaf Education and the unique needs of our students, they learned quickly and empowered the teachers to organize and take a stand for the school our students deserve.”

“LAUSD is finally listening to the Deaf community and Deaf Education experts,” says Stephanie Johnson, Marlton’s UTLA chapter chair and a Deaf teacher for first- and second-graders who has been at the school for nearly 20 years. “We could not have accomplished this without UTLA’s support.”

Marlton educators will continue to push for positive changes to benefit students, teachers and classroom conditions with union support.

“We still have a long way to go,” says teacher Laura Carls. “But knowing our union brothers and sisters are behind us — and support us — helps us to keep hope alive that things will change for the better.”

Deaf Education through the years

Before the 1860s, sign language was

popular among the Deaf community and also supported by the hearing community.

The hearing community believed that sign language brought deaf people closer to

God, which created sign language acceptance.

In the late 1860s it was argued that sign language was not a

natural language. Support for oralism — teaching Deaf people to communicate by

the use of speech and lip-reading rather than sign language — increased.

Oralists believed that sign language made Deaf people “different” and therefore

abnormal. Sign language was forbidden. Punishment included forcing

students to wear white gloves tied together to prevent them from using signs.

Oralism continued until the early 20th century. Deaf

children who were not successful under the oral method were transferred to sign

language classes and considered “oral failures” who would never know anything

or be able to make it in the world.

After ASL was recognized as a language by William Stokoe in

1960, residential programs in the United States began to adopt the Total

Communication approach, which allowed schools to offer sign language along with

speech classes, cued speech and other communication modes in classroom

teaching. By the 1990s, the Bilingual-Bicultural approach was adopted by many

Deaf schools, including Marlton, where students develop cognitive and

linguistic skills needed for ASL and English literacy.

“Full inclusion” — in place since the 1975 law that became the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act — lets Deaf students attend regular classrooms with interpreters. However, many in Deaf Education believe this can lead to isolation, since students lack peers to speak with directly. Regardless of program placement, all Deaf students receive an Individualized Education Program (IEP) that outlines how the school will meet a student’s individual needs.

Glossary

Terms associated with Deaf Education and the Deaf community

deaf with a small d

Describes a medical condition of not hearing.

Deaf with a capital D

Indicates those who associate themselves with Deaf culture including Deaf history, traditions, beliefs and behaviors. This story uses Deaf in an all-inclusive manner to reflect people who may identify as Deaf, deaf, DeafBlind, hard of hearing or late-deafened (where individuals lose their hearing over time or suddenly become deaf, which can happen at any age).

Hard of hearing

The same as being deaf with partial hearing loss.

Hearing impaired

A derogatory term in the Deaf community, since members consider themselves neither hearing nor impaired.

American Sign Language (ASL)

A complete language for Deaf people with its own vocabulary and grammar that differ from English. The perception is that ASL is easy to learn, but many compare its complexity to Arabic or Japanese. Researchers — and educators in Deaf Education — recommend Deaf students master ASL to develop their metalinguistic skills so they can more easily learn to read, write and speak (if applicable) in English.

ASL-English bilingualism

Designed to facilitate early language acquisition in both a visual language (ASL) and a written/spoken language (English). This approach can be implemented to meet the individual needs of children with varying hearing levels and varying levels of benefit from listening devices.

Cochlear implant

A surgically implanted device that provides a sense of sound to a person with severe to profound hearing loss. Cochlear implants bypass the normal acoustic hearing process, instead replacing it with electric hearing. Implants are not a “cure” for deafness — deaf people don’t understand speech perfectly as soon as the device is activated. They must spend months or years working with speech therapists, learning how to process this unfamiliar sensory input.

Language deprivation

Occurs in Deaf children when they are not exposed to an accessible language during their first few years of life, a critical period for language acquisition.

Audism

Term used to describe a negative attitude toward Deaf or hard of hearing people. It is typically thought of as a form of discrimination, prejudice, or an unwillingness to accommodate those who cannot hear.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment