Imagine a new planet similar to Earth has been discovered and you are asked to help build the first city there. What would you name the city? How would you ensure it meets the needs of people who live there? Where would you even start?

These were just a few of the questions that educator Tess Dickerson asked her kindergarten class in 2017 for a project using an innovative approach called “design thinking.” Assisted by a buddy class of fifth-graders, these kindergartners identified needs and developed idea before building prototypes of these ideas, like a slide for city residents to ride from their hotel to a nearby restaurant. After testing and refining their ideas, the students built their city out of recyclables.

“We spent the whole morning building,” says Dickerson, a teacher with Vista Unified School District and member of the Vista Teachers Association. “I don’t know how many times I heard the kids say, ‘This is the best day ever!’ ”

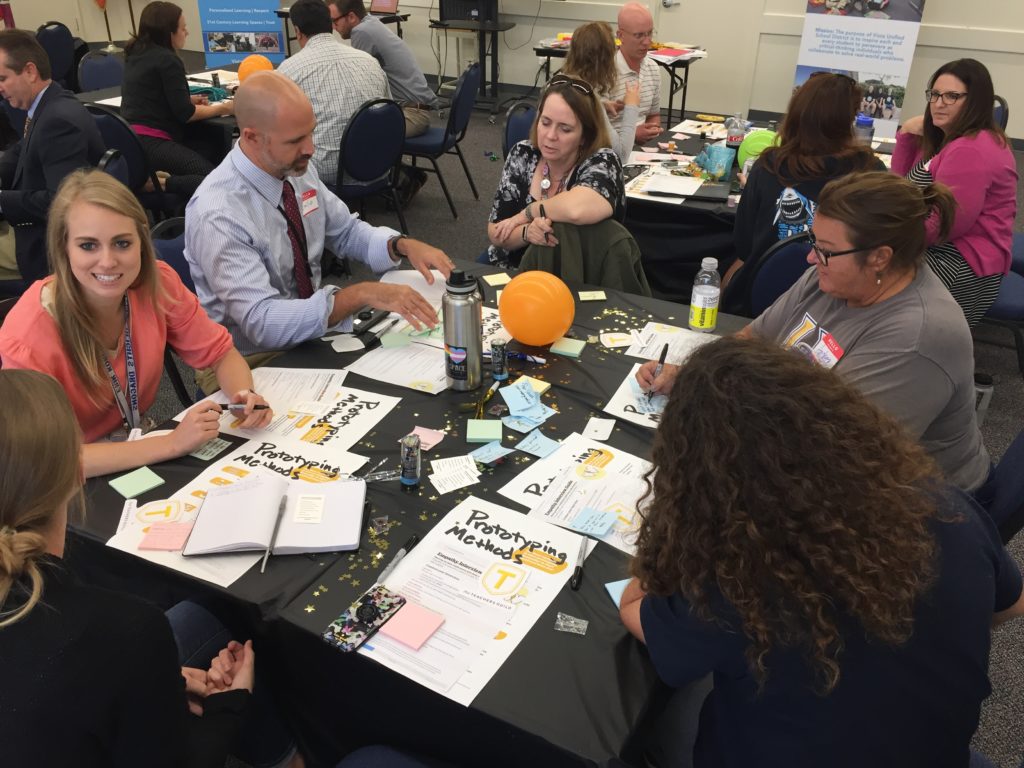

Vista educators take part in a Creative Leadership Institute in September to develop their design thinking skills.

“ I tell the kids that mistakes are great because that’s when we learn, and I realized I wasn’t living up to that. Letting go of control helps educators grow, just like we ask students every day.”

— Tess Dickerson, Vista Teachers Association

In the test stage of design thinking, students have built the cities they brainstormed.

Design thinking is an approach to creative problem-solving that focuses on professional design methods, like empathizing and experimentation, to develop innovative solutions to questions or problems. Birthed in the 1950s, it initially guided the creation of new products that solved consumer problems or fulfilled certain needs, before starting to appear in education a couple of decades later and more frequently in the 2000s.

In design thinking, students follow a six-step process that encourages the same kind of thinking process an inventor or engineer would use. But instead of inventing a better light bulb or designing a freeway interchange, students explore issues that are relevant to their lives. This year, Dickerson’s kindergartners are pondering “How do you stay safe at school?”

“What does safe mean? It gets kids thinking about their part in the community. They become aware of their place in this world and how other people think about things,” Dickerson says. “When we give them this kind of foundation, it validates them as learners and individuals. Everybody can be a part of the process, have an idea or draw a picture.”

The design thinking program at Vista is a partnership between global design firm IDEO and The Teachers Guild, a professional community created to activate teachers’ creativity to solve major challenges in education. IDEO provides the design for learning techniques and foundation, while The Teachers Guild provides resources and support for implementation. Vista is one of three Teachers Guild chapters in California (along with Oakland and Fremont) and seven nationally.

Teachers Guild director Molly McMahon says that al l teachers are inherently designers, and design thinking serves the near-constant need for educators to creatively problem-solve from the lens of their students and communities.

“In the design thinking process, there is a strong focus on empathy in the work we do,” she says. “We tell teachers: ‘If you’re going to create change, you start with yourself, your own biases; start with questions and not answers; and believe that you can create change.’ So we create opportunities to understand yourself and others. Equity and innovation go side by side.”

Learning to let go of control

English teacher Vickie Curtis is one of eight “design leads” and oversees the design thinking program in Vista. Working closely with The Teachers Guild, Curtis helped facilitate workshops that taught the approach and each stage of the process. Vista educators were then given their own design challenge to complete: “How can we make learning more relevant for our schools?” Curtis says her fellow educators worked on ideas for that question all year in their classrooms before reconvening at the end of the year to share their ideas.

“It was really inspiring to see how teachers made the work relevant to education,” she says. “It can be scary for teachers and it can be a risk, but that’s the beautiful part.”

Giving students control of the learning process and guiding their experience is a major part of using design thinking in the classroom, says Paula Mitchell, an Oakland Unified elementary school teacher and design lead in the Oakland chapter of The Teachers Guild. There, the Guild partners with educators from public, private and alternative settings throughout Oakland to support their creativity in reaching students using design thinking.

The 25-year educator says the empathy step of the design thinking process forces educators to take stock of students’ diverse needs and create lessons that are relevant to their experiences.

“Even though we talk about students being the center, with all the mandates and obligations, we often forget about our learners,” says Mitchell, an Oakland Education Association member. “Creating more empathy for our learners and their needs has been really useful. It’s getting to know our students in a different way. That’s been some of the most valuable work we’ve done so far.”

Mitchell says this empathy led to ideas like providing therapy animals for stressed students and a “shadow project” where students take photographs of their days to provide visual representations of their daily experiences.

Educator Cicely Day was involved in the Oakland Teachers Guild chapter in 2017 before moving to West Contra Costa Unified School District last year to run a high-tech “Fab Lab,” where students use computers, 3-D printers and other professional machines to bring their ideas to life. She says that design thinking gives students and teachers alike the tools and courage to find new ways to solve problems.

East Bay educator Cicely Day, participates in an Oakland Teachers Guild workshop.

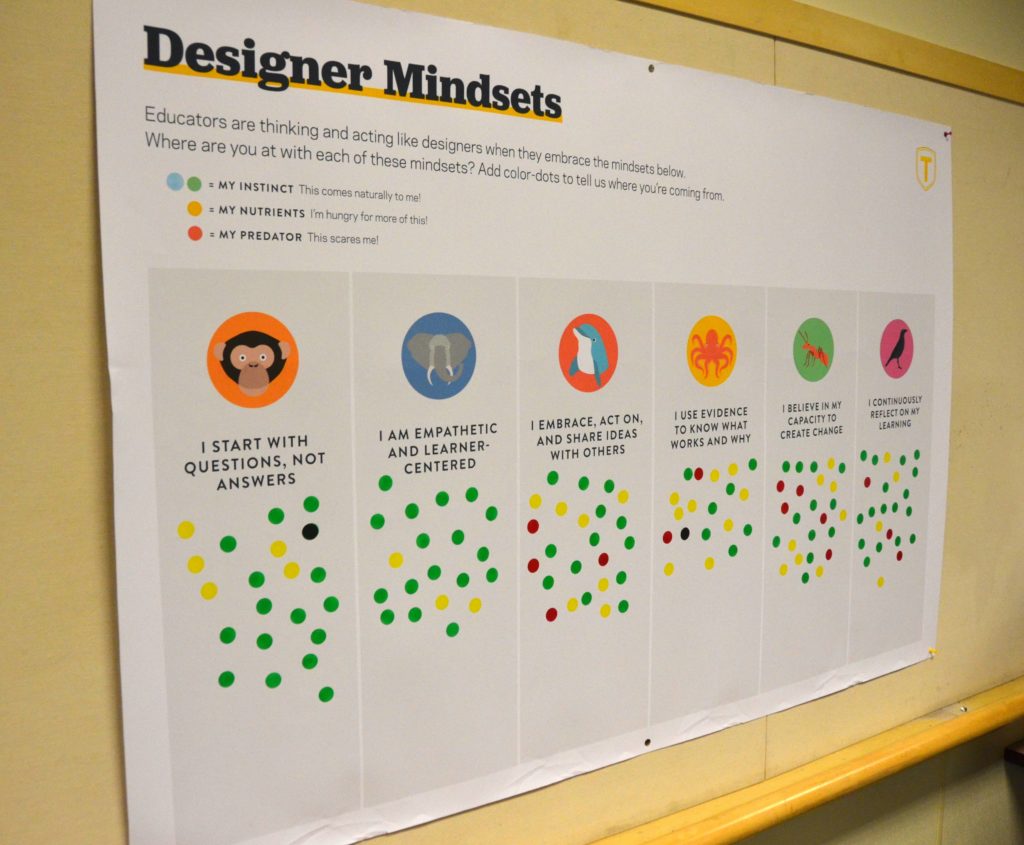

Each designer mindset comes with its own set of motivations.

“I really like the process because it frees you up from the constraints of the system to try new ideas,” says Day, now a member of United Teachers of Richmond. “For my students, mostly girls, giving them permission to fail and think outside the box is refreshing.”

Being all right with mistakes and even embracing minor failure as a precursor to a major learning moment is a key piece to design thinking, says Dickerson, who notes that adults could glean a lot from her kindergartners, their sense of wonder and lack of self-imposed limitations.

“Younger kids are willing to do almost anything,” she says, explaining that the fearlessness of her kindergartners is what finally convinced her to join The Teachers Guild. “I tell the kids every day that mistakes are great because that’s when we learn, and I realized I wasn’t living up to that. Letting go of control helps educators grow, just like we ask students every day.”

Design lessons that speak to students

An approach that makes learning relevant to students and empowers them to take control of the process hit home for Emilie Barnes, 14, a ninth-grade student who learned design thinking in middle school with Curtis.

“ In design thinking, there is a strong focus on empathy in the work we do. We create opportunities to understand yourself and others. Equity and innovation go side by side.” —Teachers Guild director Molly McMahon

“It made us slow down and think about what we’re doing, what’s the problem, how can we solve it, and made us think,” Barnes says. “It’s a good skill for us to have in real life, so when a difficult situation or problem occurs, we can stop and think about it logically.”

This empowerment comes with responsibility too, Curtis says, as students learn to get rid of their preconceptions and empathize with others to find innovative solutions that consider their needs. This causes students to see how issues are bigger than the questions before them.

“We got the full picture and really thought about how we could help the person and see them as a person — not a problem that needs a solution,” Barnes says.

This applies to educators as learners as well. In Vista, one of the challenges posed to educators during a Teachers Guild workshop was to redesign the staff lounge at school. Dickerson says this experience helped bring home how her students were learning.

“I got to feel what it was like to be a student,” she says. “You need to go through the process yourself — you’ll see what it’s like for them. If you’re enjoying it, it’s easy to see how the students will enjoy it.”

Fremont springboards into innovation

In Fremont, educators are just getting started on their design thinking journey. Seventh-grade teacher Chelsey Staley is putting the finishing touches on the design challenge she’s creating called a “passion project,” which asks students to consider what they can do to help people and improve their community. Among her students’ ideas: create a YouTube channel for educators to communicate with students in a medium they use every day; change the school lunch program at their school and across the state; and find ways to stand up against bullies on their campus.

Fremont educators immerse themselves in design thinking at their Creative Leadership Institute.

“They are very motivated to stop bullying on campu and have asked, ‘How can we get to the root of bullying?’ and ‘How can we stand up for those that are being bullied?’ ” says Staley, a Fremont Unified District Teachers Association (FUDTA) member. “I know my students enjoy the freedom design thinking allows them. I work with 12- and 13-year-old kids, and getting them interested in school takes a lot of work. Through the design thinking process, I have gotten more interest than anything else I’ve tried so far. Design thinking is here to stay in my classroom.”

At Fremont’s American High School, English teacher John Creger has been finding innovative ways to engage students for 30 years, many of which share core principles with the design thinking approach. Notably, Creger has worked to build empathy in his 10th-grade students, asking them to embark on a yearlong project centered around the question of how a sophomore can help build a caring world.

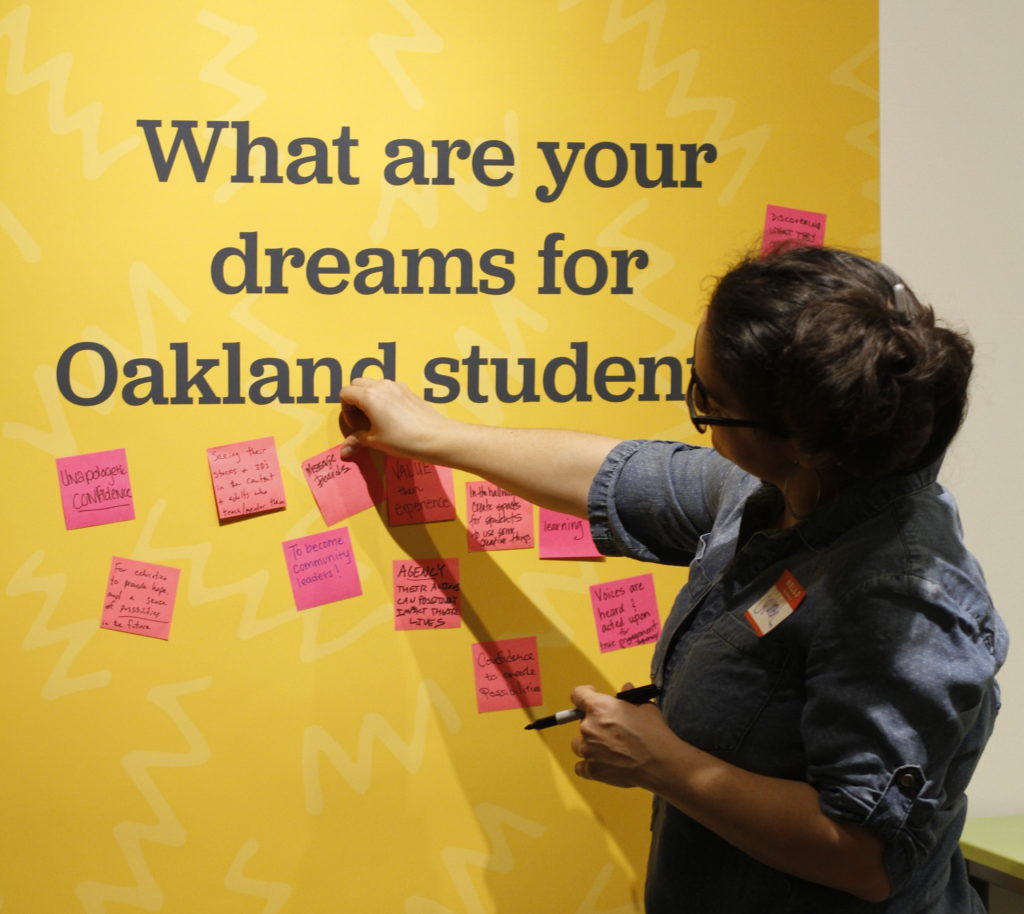

At the Oakland Innovation Summit, Salomeh Ghorban, an educator and leader in the Teachers Guild Oakland Chapter, shares her dreams for students.

Creger says the empathy step of IDEO’s design thinking process sets it apart from other approaches he’s used previously. He says the emphasis on caring works well with sophomores and allows them to focus on deeper needs instead of getting distracted by abstract concepts. With that focus on empathy in mind, he is embarking on a district-level Teachers Guild project to incorporate the developmental needs of each stage of childhood into the district’s curriculum, so that teachers have the incentive and guidance to help students develop as well as learn.

“The Teachers Guild may well be the most encouraging development I’ve seen come to Fremont in my 30 years teaching here,” says Creger, a FUDTA member. “Unlike previous moves from the corporate world, this one does not dictate outcomes or processes, but equips teachers with rich innovation skill sets, trusts us to identify needs, and backs us as we design to meet them.”

6 Steps of Design Thinking

The design thinking approach uses a six-step model to develop innovative solutions to problems. The model can be applied to nearly any question or problem, from the classroom to home life to global issues.

Empathize: Discover the needs of students, users or people in the community, and reflect on evidence to see the problem or question from the end-user’s perspective. Empathy is the foundation and inspiration of any user-centered design process.

Ideate: Generate new ideas through structured brainstorming that encourages thinking expansively and without constraints. No idea is too wild when ideating especially because unorthodox ideas can often spark visionary thoughts.

Build: Make ideas tangible by building a prototype. The Build step brings to life the most promising ideas from th previous step. These early and rough prototypes can be tested to help improve and refine ideas.

Test: Try out prototypes and get feedback from end-users. The Test step is the most critical phase of the human-centered design process. Without testing, it is unknown whether the solution is on target or the idea needs to evolve.

Iterate: Refine ideas based on feedback from end-users and use that information to fuel design changes. There are usually multiple iteration, testing and feedback integration stages to fine-tune the solution.

Share: After making sure the solution meets the end-users’ needs and getting details just right with the design, it’s time to share your ideas with the world and inspire others to try them.

Discover Design Thinking

Educators do not have to be part of an official Teachers Guild cohort to take advantage of the wealth of resources on design thinking available online, including a free toolkit produced by the Guild.

The site also provides a collection of plans and projects undertaken by educators in schools across the country, and a forum to share ideas. Paula Mitchell in Oakland says the Guild is a supportive community where educators share ideas and “lift each other up in service of students.”

“Teaching can be so isolating sometimes. Organizations like The Teachers Guild bring educators together to share and support,” she says. “The great thing about design thinking is it really just encourages you to try.”

Fremont’s John Creger says the Guild partnership of many education stakeholders is a welcome change in approach, centering efforts around what matters most. “It was refreshing to convene not in our usual school or district enclaves, but in the heart of the community, partnered up from Day 1 with community members who care about what we do and who we do it for, and want to be involved.”

Chelsey Staley in Fremont says that students learn more when teachers work together, and The Teachers Guild facilitates collaboration so educators approach learning from the perspective that nothing is impossible.

“The Teachers Guild has given teachers at my school the opportunity to work together and hear what common goals we have for the staff and students, learning from one another about topics we may never have thought of on our own,” she says. “That alone has made being a part of The Teachers Guild worth it for me.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment