Students at Salmon Creek Middle School in Occidental are well aware that climate change poses a threat to humankind. Since 2017, Sonoma County residents have been evacuated six times due to fires and flooding related to global warming.

When students learn the science of what is happening to their community and their planet, it’s traumatic, says sixth grade teacher Park Guthrie, a member of Harmony Union Teachers Association. Some students become upset; others pretend not to care or make jokes to protect themselves psychologically.

“But no matter how they react to this terrible realization, all of the kids have the same question. They all ask why,” Guthrie says. “They want to know why adults haven’t taken care of this, why we are still investing in fossil fuels, and why we are still having debates about climate change.”

His students have a reason to point fingers. USA Today reports that people under 40 will experience an “unprecedented life” of disasters including more heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, flooding and crop failures — all related to global warming.

A September 2021 study by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communications shows that the majority of parents believe it’s important for their children to learn more about climate change. The study also reports that teachers need more training and support to implement climate change instruction in the classroom.

More resources are coming

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill last July allocating $6 million to create education resources on climate change and environmental justice. The landmark legislation will provide free, standards-based curricular resources to all K-12 teachers and students in California, through a partnership between the San Mateo County Office of Education (SMCOE) and Ten Strands, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing student environmental literacy.

“The grant money from the state should arrive soon, and the curriculum should be available in 2024,” says Andra Yeghoian, environmental literacy and sustainability coordinator for SMCOE.

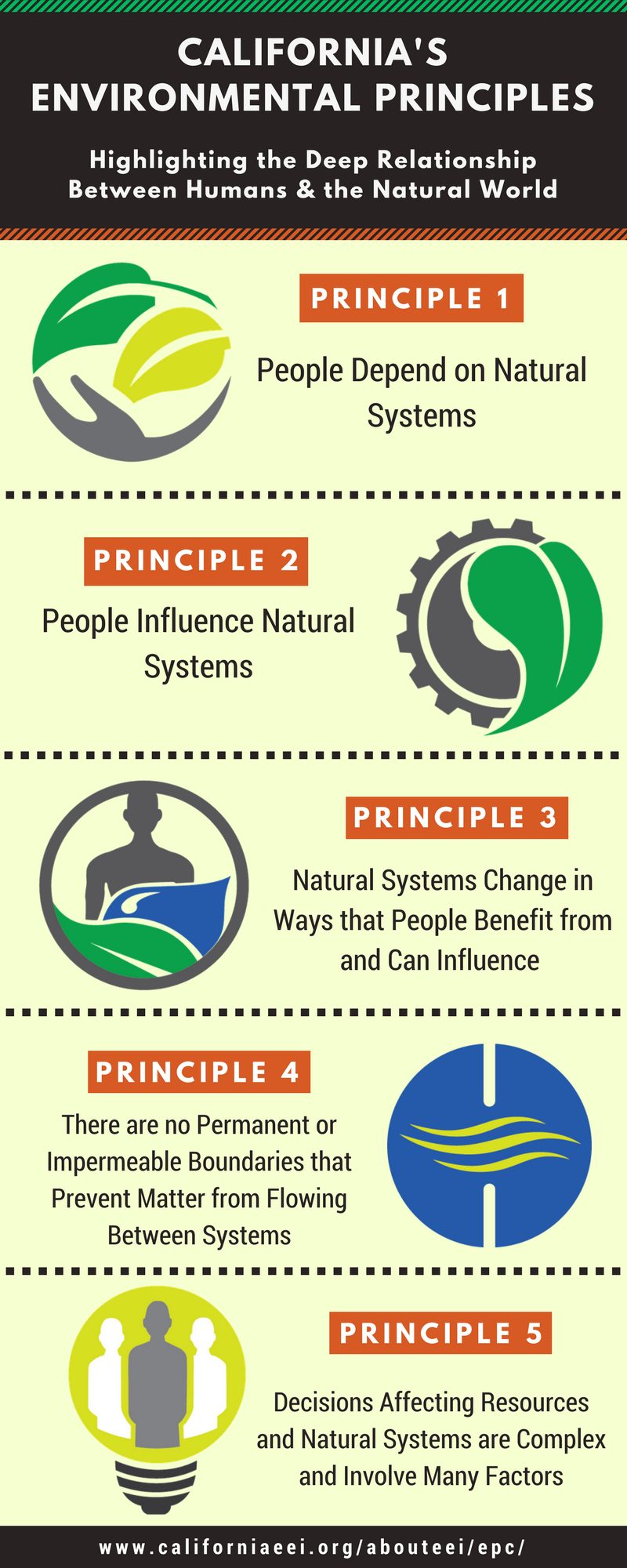

“It’s critical for California to teach environmental literacy. And it’s critical that it be embedded into all subjects by incorporating the state’s Environmental Principles and Concepts [EP&Cs].”

The EP&Cs were approved by legislation in 2004 and created collaboratively by the California Department of Education, the Environmental Protection Agency, and other public agencies, with more than 100 scientists. They are integrated into the state’s curriculum frameworks for science, history and social science, and health. They will also be included in the upcoming mathematics framework.

In 2018, they were added to the Education Code by Gov. Jerry Brown. As part of that same bill, climate change and environmental justice were added to the list of topics covered by the EP&Cs, clearing the path for the recently allocated funding. Ten Strands worked with state Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica) on both advocacy efforts.

The new curricular resources will be “trauma-informed,” says Yeghoian, acknowledging that learning about climate change can be scary if not framed in a way that is empowering.

“The resources will emphasize teaching about this topic in a way that allows students to feel hope and possibility instead of despair and apathy,” says Yeghoian. “There will also be an emphasis on environmental justice, Project-Based Learning (PBL), and professional development for teachers.”

“The kids all ask why — why adults haven’t taken care of this, why we are still investing in fossil fuels, why we are still having debates about climate change.”

—Park Guthrie, Harmony Union Teachers Association

Occidental activists

PBL at Salmon Creek Middle School started with small steps, and eventually made a nationwide impact to increase awareness that the Earth is warming.

Guthrie founded the Schools for Climate Action Club in 2016 with his two children, then students at the school. Members of the after-school club met with leaders of school boards and the California Association of School Psychologists, asking them to speak up for climate justice.

In 2017, Guthrie founded Schools for Climate Action (SCA), a nonprofit that helps school boards, teachers unions, student councils, and other educational organizations draft and adopt climate action resolutions. These resolutions acknowledge the threat of climate change and offer plans to reduce impacts from carbon emissions.

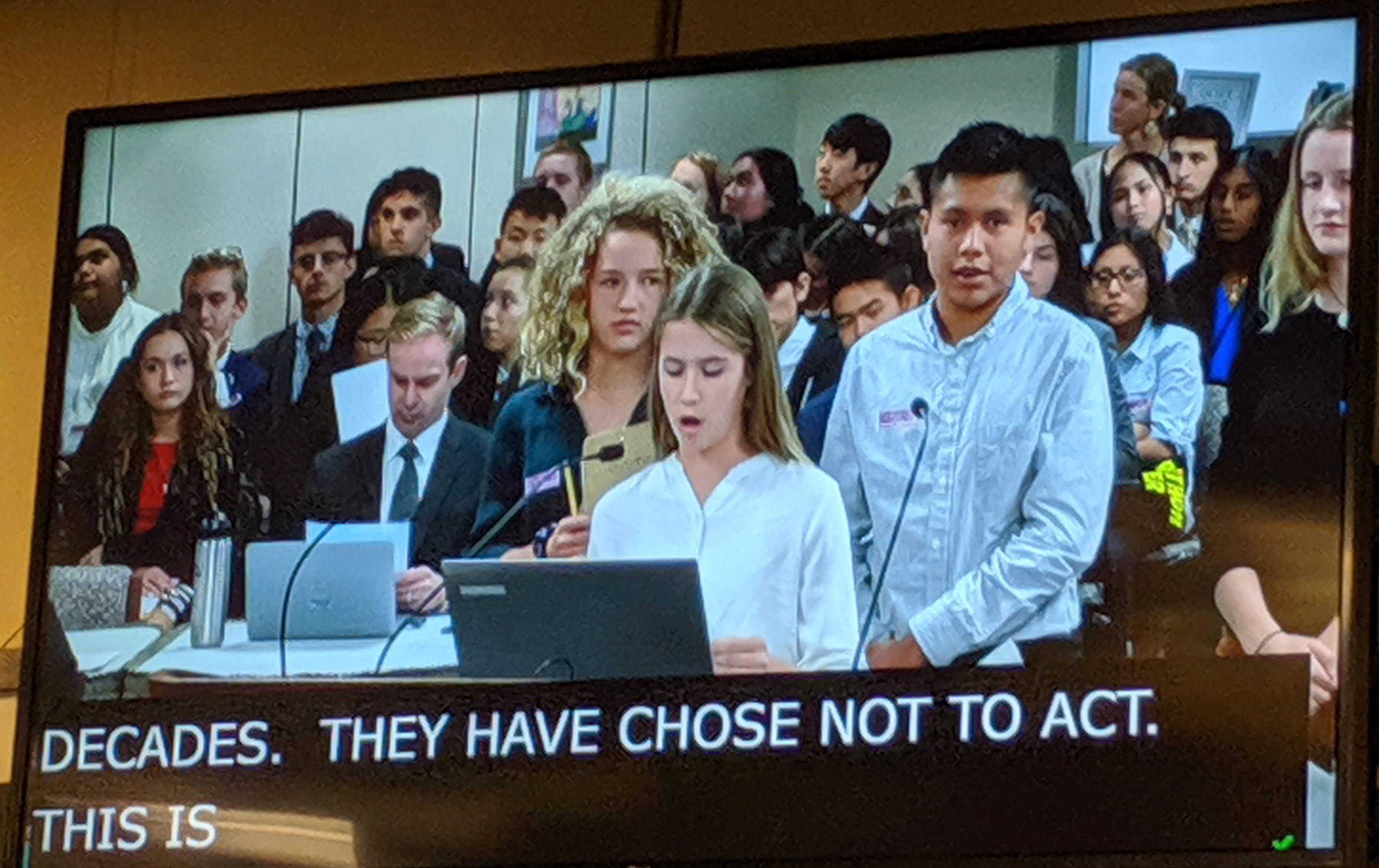

Two Salmon Creek students, along with 150 other SCA youths, traveled to Washington, D.C., in 2018 to engage in nonpartisan advocacy for climate action. They delivered more than 50 climate justice resolutions from school boards and education organizations across the country to lawmakers. The resolutions call for creating a paradigm shift to recognize climate change as a generational justice and equity issue — and for elected leaders to support commonsense climate policies, including transitioning to clean energy.

Schools for Climate Action students address the State Board of Education in Sacramento in November 2019.

Guthrie is proud to see students pressure lawmakers to take action. In his classroom they write letters, create artwork, and ask school boards, student councils, school environmental clubs, PTAs and other organizations to speak up and pass resolutions. They planted redwood trees on campus as a carbon sequestration project.

“We all have the chance to use our voices for the better,” says Savanna Conwell, a former Salmon Creek student who is now a high school sophomore. “Despite the ominous chatter about the climate crisis and its drastic effects, there is still great silence among those in power to do something about it. This is why it is so important to educate our youth about the climate crisis. We will be the generation to change our world. We will be the generation to fix the mistakes of those in the past. We will be the generation of innovation and saviors. We are our planet’s last hope.”

“We can either cry about it or we can do something about it. It’s the largest social problem and environmental justice issue facing students, so how are you covering it in your classroom?”

—Joseph Senn, Oakland Education Association

Oakland students step up

Students at Oakland Technical High School persuaded the Oakland Unified school board to make teaching climate change a higher priority. To accomplish this, they enlisted support from AP environmental science teacher Joseph Senn. They also received support from the Sierra Club’s climate literacy program and students from Portland, Oregon, who successfully sued their district for doing them a “disservice” by not teaching about climate change.

In January 2019, following a student presentation, the Oakland Unified board updated its policy on environmental education to mention climate change specifically and commit to connecting district sustainability projects like solar panels and school gardens to environmental education.

It was good for students to see the fruits of their labor, says Senn, a member of Oakland Education Association. But the pandemic and a budget shortfall have delayed implementation.

“Students want to make sure climate change is tied into all K-12 subjects and not just included in science literacy. Hopefully, that will happen,” Senn says. “Meanwhile, the board is creating a work group on how to address implementation. What teachers really need is leadership and trainings.”

Senn acknowledges that educators have never had more on their plate, and it’s easy to put climate change on a back burner. But the urgent threat to the planet should not be ignored.

“We can either cry about it or we can do something about it. My question to teachers is this: It’s the largest social problem and environmental justice issue facing students, so how are you covering it in your classroom? Please take the time. There are resources to help you.”

“We have to educate our children about climate change. Hopefully, they can make changes and reverse some of the damage that’s been done.”

—Veronica Garcia, Garden Grove Education Association

Garden Grove stewards of the Earth

Veronica Garcia, a seventh and eighth grade science teacher at Louis Lake Intermediate School in Garden Grove, finds real-life examples to help students understand what is happening to the Earth.

“We study evolution and talk about animals that have gone extinct — and why. We talk about the power grid and why it went out in Texas. We discuss alternative energy like solar and wind power. We study fracking and how it contributes to air pollution and more carbon emissions. We look at plastics, which are made from oil, and how it harms the ecosystem and why so much plastic packaging is unnecessary.”

Garcia, a member of Garden Grove Education Association, encourages students to see themselves as stewards of the Earth. She is educating herself on ways to help students make a difference and has found support from the NEED project (National Energy Education Development), a nonprofit organization that offers K-12 curriculum on energy and conservation. Last semester she taught a new elective, Discovery Science, which has units on climate change.

Garcia also shows The Twilight Zone episodes that once seemed futuristic, such as “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” where suburban residents battle each other when they lose power, or “The Midnight Sun,” where two women cope with oppressive heat and a lack of water. At first students wonder why they are watching old black and white TV shows, but they soon see the connection with today’s climate crisis.

“We have to educate our children about climate change. They are the future. Hopefully, they can make changes and reverse some of the damage that’s been done.”

“It’s important that students see there are solutions. If we tell them there are no solutions, why would they care?”

—Pia VanMeter, Riverside City Teachers Association

Riverside looks at sea change

Pia VanMeter, a marine biology teacher at Martin Luther King High School in Riverside, says most people believe climate change occurs on land, not sea. But oceans absorb most of the excess heat the planet produces.

“The biggest threat to our oceans is that they are becoming more acidic,” says the Riverside City Teachers Association member. “The ocean is absorbing more CO2 from the atmosphere. This is changing the chemical composition of the ocean that affects the amount of carbonate ions needed by calcifying organisms such as oysters and calcareous plankton, which affects the entire food chain. Coral bleaching occurs as a result, as well as increasing temperatures. The sustainability of our oceans is threatened.”

A new study by the Monterey Bay Aquarium finds that global warming reached a turning point in 2014, when more than half of the world’s oceans experienced extreme heat. Marine heat waves, which hit the California coast from 2014 to 2016 causing environmental disruption, are becoming more common and severe.

Another recent study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that sea levels will rise as much as 6 inches in California and along the West Coast by 2050, and that major flooding will occur five times as often in the next three decades as it does today.

VanMeter says students are eager for the truth and want to avoid “fake news” that is circulating. Some have done field studies with the Birch Aquarium at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, visiting tidepools and collecting biodiversity data through the years. Their research shows less biodiversity compared to previous years — and an explosion of sea urchins and fewer starfish.

“We share our data with Scripps and record observations. It’s not just students writing a paper; it’s real science.”

Students are also concerned about the vast increase of plastic in the ocean, its impact on marine life, and the fact that plastic is created by fossil fuels. They have created public service announcements about the threat to the world’s oceans. VanMeter conducts Socratic seminars where they have deep discussions and look for solutions.

“It’s important that students see there are solutions. If we tell them there are no solutions, why would they care? We need them to care, because they will hopefully be the generation that can change things.”

“I am trying for a more centrist approach of bringing people together regardless of politics, so we can look at this seriously, come together and take action.”

—Jon Larson, Sierra College Faculty Association

Tahoe students face the new normal

Sierra College’s Truckee campus sits in a location where extreme weather is becoming the new normal. Jon Larson, a professor who teaches environmental studies and a class on energy and the environment, points to recent extremes of too much snow or too much drought. He explains that natural variability in the climate system is becoming more pronounced with a clear human influence.

Larson conducts underwater research in Lake Tahoe, which draws thousands of vacationers. He believes higher temperatures and invasive species are causing the once crystal-clear water to become murkier. He recalls the Caldor Fire came close to devouring the bone-dry Lake Tahoe Basin last year, resulting in mass evacuations.

Larson encourages students to calculate their carbon footprint and lower it with the help of The Nature Conservancy at nature.org. (See “Resources for Teachers” sidebar below.) A carbon footprint is the total amount of greenhouse gases that are generated by one’s actions.

“My most popular lecture is how I accomplished this myself,” says the Sierra College Faculty Association member. “I finally decided to change my lifestyle after teaching about this over a decade.”

He installed solar panels on his house, with local subsidies that made it more affordable. He bought an electric car, figuring that money saved on gas would more than compensate for the cost of the car, which has proved true. His philosophy is: “You can’t change the world unless you change yourself first.”

Some college students tell him they believe climate change is part of “God’s will” or that God will take care of the Earth, so people needn’t worry.

“I say, ‘You may be right, but meanwhile, let’s move forward and be informed by science, which has brought us a long way so far.’ The purpose of my class is to focus on the science.”

Larson worries that the climate of political polarization has hindered peoples’ ability to find common ground and work toward finding real solutions.

“We’re being pushed to such extremes that people either think climate change is a hoax or that we’re all doomed. I am trying for a more centrist approach of bringing people together regardless of politics, so we can look at this seriously, come together and take action.”

Students with Schools for Climate Action on the steps of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., in 2018.

A Social Justice Issue

Salina Gray teaches integrated science at Mountain View Middle School in Moreno Valley. She received her doctorate from Stanford University in science education, with a focus on social justice. When it comes to teaching climate change, that’s still her focus.

“Whenever there’s an issue facing any aspect of society, people struggling financially and those who have been historically marginalized suffer more,” says the Moreno Valley Educators Association member. “This applies to the environment; those with fewer resources and infrastructure suffer more from extreme weather.”

USC Rossier School of Education’s 2021 talking points for teaching climate justice agree:

- Food insecurity due to flooding and crop failure affects people of color adversely.

- Urban neighborhoods with more pavement and fewer trees experience higher temperatures, increasing the risk of heat illness, especially for those who lack access to air conditioning.

- Indigenous communities are losing their homes due to rising sea levels and drought.

- People of color are more likely to experience property damage and homelessness from catastrophic climate events.

Salina Gray

Gray sees the connection between climate change and the social justice/anti-racism movement growing in importance — especially since the World Health Organization believes that climate change will cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths between 2030 and 2050.

Her class incorporates the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for taking urgent action on climate change.

She also teaches the story of the hummingbird by 2004 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wangari Maathai of Kenya. A forest is on fire, and the animals watch helplessly as it burns. When a small hummingbird flies to the nearest stream and spreads drops of water on the fire as fast as it can, the other animals tell the bird that it is too little and a drop of water doesn’t have much impact. But the hummingbird refuses to be discouraged and tells them, “I am doing the best I can.”

“The point of the story is that we are all hummingbirds,” says Gray. “We should all be doing the best we can to save our environment.”

Resources for Teachers

- A carbon footprint is the total amount of greenhouse gases that are generated by one’s actions. Calculate yours at nature.org (under the “Get Involved” tab).

- NASA Global Climate Change, climate.nasa.gov, and NASA Climate Kids, climatekids.nasa.gov.

- NASA Earth-Now, a free app (iOS and Android) that allows students to manipulate color scales on a 3D model of Earth and see reports on temperature, carbon dioxide, sea level and other climate factors.

- National Center for Science Education, ncse.ngo.

- National Geographic lesson plans and educational videos, tinyurl.com/NatGeoClimate.

- Center for Sustainable and Climate Resilient Schools climate literacy resources, tinyurl.com/ClimateLiteracyResources.

- Climate justice teaching resources, National Science Teaching Association, tinyurl.com/STEMClimateJustice.

- Global Oneness Project, resources and toolkits on the impact of climate change on people and communities, globalonenessproject.org.

- Sierra Club San Francisco Bay chapter’s climate literacy page, tinyurl.com/SCSFClimateLiteracy.

- Schools for Climate Action, a nonpartisan campaign with a mission to empower schools to speak up, schoolsforclimateaction.weebly.com.

- Documentary: An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power (2017), Al Gore’s sequel to An Inconvenient Truth (2006).

A Few Facts

- Human influence has unequivocally warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. The last decade was the hottest in 125,000 years.

- The ocean absorbs most of the heat we produce, threatening coral reefs and marine life. We are losing 1.2 trillion tons of ice each year.

- It could become too hot to live in many places by the end of the century, with unbearable temperatures affecting up to 3 billion people.

- Natural disasters — drought, flood, fires, hurricanes and storms — can be attributed to human-driven climate change, which has not always been the case.

- When fossil fuels burn, they release large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the air, which traps heat in our atmosphere, causing global warming. CO2 is at its highest level in 2 million years.

- Global warming is partially reversible if we take action soon. Our future depends on it.

Compiled by Earth.Org

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment