Photos by Scott Buschman

Have one or more of your students suddenly started sporting designer shoes and bags? Or maybe you see that they’re now handling two cellphones? Or perhaps you’ve noticed a new tattoo with someone’s name or initials, on their chest, neck or elsewhere?

These students may be victims of sex trafficking, defined as exploiting someone through force, fraud and coercion for the purpose of commercial sex. It’s an epidemic in California, which has the highest number of incidents reported in the U.S., and many juvenile victims are enrolled in the American school system, according to a 2015 report from the U.S. Department of Education, “Human Trafficking in America’s Schools.”

While the term “sex trafficking” conjures up images of someone being kidnapped and sent to a foreign country, such as in the movie Taken, most incidents are domestic. Sex trafficking is just one form of human trafficking, which may provide domestic servants or agricultural workers, or force students to sell magazines or candy door to door without pay and under abusive conditions. Many youths in forced-labor situations — a form of modern-day slavery — are also sexually abused and trafficked for sex, according to the report.

No community is immune, but it’s shocking when it happens in yours.

Sara Neze-Savacool

“We had a storefront just six blocks from the high school that was shut down because human trafficking was taking place,” says Sara Neze-Savacool, a French teacher at Antioch High School. “We know it’s happening here around us in Contra Costa County. But it’s a tough topic to learn about, and it’s not well publicized. I would like our district to find resources to start an education campaign, so children can learn to protect themselves.”

Nearby Oakland is the No. 1 city in the world for human trafficking, says Heather Hoffman of 3Strands Global Foundation, an El Dorado Hills-based nonprofit dedicated to prevention. Other hotspots are Los Angeles, Sacramento, Long Beach, San Francisco and San Diego.

Hoffman is one of several experts who addressed educators during San Diego High School’s multiday training for teachers, counselors and administrators this spring. The workshop focused on prevention, recognizing the signs that a student is being trafficked, and how to help students if you think they are being exploited.

Rickeena Boyd-Kamei, left, and Heather Hoffman at a training for educators at San Diego High School on how to recognize signs of trafficking and what to do.

San Diego Education Association member Rickeena Boyd-Kamei helped organize the event, which included a former human trafficking victim and a workshop for parents to increase awareness. She was instrumental in San Diego High’s decision to implement curriculum for students in AVID classes (where students learn skills to be successful in college), so they won’t be naive if they encounter sex trafficking recruiters online, in shopping malls or even on campus.

Malcolm Robinson, an 11th-grade AVID teacher at the high school, is glad to see his district take a “cohesive approach” rather than having every teacher taking an individual stance.

“There’s never enough time to teach everything, but you have to carve out time for a topic that is life or death. I had a young lady with bad attendance, and I found out later that she was engaging in exotic dancing across the border.”

Teaching about human trafficking is now the law

The Human Trafficking Prevention Education and Training Act (AB 1227), passed by the state Legislature in 2017, requires all public schools to offer education and training about human trafficking to staff and students beginning this year, with a focus on identification and prevention. Introduced by Assembly Member Rob Bonta (D-Oakland), sponsored by 3Strands, and supported by CTA and others, the bill went through the legislative process without a single no vote and was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown. California is the first state in the nation to adopt such a mandate.

Malcolm Robinson, 11th-grade AVID teacher at San Diego High School, speaks up during the training.

(Gov. Brown signed bills in 2016 to decriminalize prostitution for minors because they are underage and therefore victims. One bill allows minors under the age of 16 to testify through closed-circuit television so they do not have to face their pimp.)

Boyd-Kamei strongly supports the new law, which requires schools to take the lead in educating youths, beginning in seventh grade. Her district has worked closely with 3Strands to create curriculum designed to teach students to develop self-confidence, recognize healthy relationships, identify predators, and obtain help for peers who may be involved in human trafficking.

“Teachers are focused on providing children with things they need to be successful in life, such as how to write, do math, and be equipped for college and the world of work,” says Boyd-Kamei, a home hospital teacher. “But if students are intercepted by human traffickers, all this work could be for naught, and the psychological and physical effects are immense. In extreme cases, young people die in the hands of traffickers or buyers. So it is critical for educators to become involved and educate students, parents and the community about predators.”

In February, Sacramento City Teachers Association President David Fisher thanked the Assembly and the governor for supporting AB 1227. He noted media reports about several Sacramento area incidents — including the arrest of a youth soccer coach on suspicion of human trafficking, and the rescue of several underage victims by police in Roseville.

“Educators are on the front lines in dealing locally with this global issue,” Fisher told lawmakers. “This fight is another teachable moment.”

How are youths recruited?

Since the National Human Trafficking Hotline was founded in 2012, more than 5,200 cases have been reported in California, more than any other state. Because it is a hidden crime, many cases go unreported.

According to a 2018 report by THORN, an international anti-trafficking organization, traffickers are increasingly relying on technology and social media to ensnare victims as young as middle school and advertise them for sex. Their survey of sex trafficking survivors shows 55 percent were recruited via texting, websites or apps. Technology also allows traffickers to keep tabs on victims around the clock and from any distance.

Experiences that make youths vulnerable are foster care, homelessness, sexual abuse, violence and bullying. Other risk factors are isolation, poverty, substance abuse, mental illness and learning disabilities. LGBTQ+ youths and young people of color are more vulnerable. Most youths continue to stay in school while being sold, reports THORN.

“It can happen to anybody’s daughter or son, at Beverly Hills High School or college,” says Stephany Powell, a former teacher and former vice sergeant with the Los Angeles Police Department, who is now executive director of Journey Out, a Los Angeles nonprofit dedicated to helping victims of human trafficking.

Stephany Powell

Powell says pimps often start relationships by romancing victims, then pressure them to be intimate with someone else for money just once. The pimp may claim, “The money is for our future.” Afterward, the victim may suffer physical abuse and threats against family members if they refuse to continue having sex with others or try to end the relationship.

Other pimps use force and abuse from the beginning, or recruit their own relatives, or offer youths a job in the modeling or entertainment industry. (For example, two girls recently tried to board a plane in Sacramento with one-way tickets to New York, Hoffman says. They told police the ticket buyer, who was a pimp, said they would be getting paid to model and perform in music videos.)

Recruitment happens at shopping malls, sporting events and even school. Pimps may even be enrolled as students — or have students working for them who befriend vulnerable peers and invite them to parties and events where they can be exploited.

“I know of a case where a pimp was a student living on campus at the University of Southern California who was hooking students up with dates for money,” says Powell. “Girls didn’t realize he was a pimp until he put their pictures up on different websites.”

According to THORN, many former victims surveyed never considered themselves victims, and many continued to romanticize their relationship with their trafficker, even after exiting “the life.” Less than a quarter surveyed saw their trafficker prosecuted. When asked if they would want to pursue prosecution of their trafficker, 88 percent reported they would not.

What to do if you suspect a student is being trafficked

This is a dilemma for educators, because many sex trafficking victims who do not see themselves as victims are scared to talk. Educators should be mindful of not risking the well-being of students unintentionally if there are trafficking networks on campus or it is related to gang activity, because a student could face retaliation.

Hoffman suggests reaching out to students privately and asking them questions devoid of blame, such as “What is going on with you?” or “Are you OK?” or “What do you need?” or telling a student repeatedly, “I’m here for you.” Building trust takes time — and sometimes numerous outreach attempts — before a student confides to a caring adult that they are being victimized. Educators, as mandated reporters, must share that information with higher-ups, even if a student begs them not to tell.

Hoffman suggests reaching out to students privately and asking them questions devoid of blame, such as “What is going on with you?” or “Are you OK?” or “What do you need?” or telling a student repeatedly, “I’m here for you.” Building trust takes time — and sometimes numerous outreach attempts — before a student confides to a caring adult that they are being victimized. Educators, as mandated reporters, must share that information with higher-ups, even if a student begs them not to tell.

“What you don’t want to do is be judgmental or ask a student to go into details,” says Hoffman. “Be a good listener. If you do report that a student is being victimized, tell the student that they may not understand what’s happening now, but you are acting in their best interests and trying to help them.”

Prevention is key

To prevent students from becoming prey, educators can integrate prevention into health and AVID lessons or even history, since human trafficking is modern-day slavery. When seeking relevant guest speakers, schools should choose those with a service provider background who know appropriate terminology and strive to create a safe environment.

Online curriculum from PROTECT, a human trafficking prevention education program developed by 3Strands Global and two other nonprofits in partnership with the California Department of Education and others, is grade-level specific. Fifth-graders learn about safe people and safe choices, are taught to listen to their “inner voice” if a situation is uncomfortable, and develop personal and online boundaries. Seventh-graders are encouraged to see themselves as worthy of respect, love and care. Ninth-graders receive an overview of human trafficking including warning signs and recruiting tactics, learn how the media and technology influence and desensitize exploitation, and are taught strategies to keep themselves safe.

“It’s important to help students develop self-confidence, understand how to build healthy relationships, and identify a predator,” says Boyd-Kamei. “Dating abuse can be a forerunner to sex trafficking. The media sometimes glamorizes the lifestyle, and girls want to make a lot of money. But when students understand it is really modern-day slavery, they don’t find it so alluring.”

Marilyn Wolfson

Marilyn Wolfson, a health teacher at Polytechnic High School in Sun Valley, brought Journey Out’s Powell into her classroom as a guest speaker. Most students had never discussed the topic with their parents before and knew little about dangers that could be lurking.

“Giving them this information may be saving their lives,” says Wolfson, United Teachers Los Angeles. “They should know how to respond if they are approached. I don’t want them to be paranoid, but they need to be aware that when someone offers them money and jewelry, it could get them into a world of trouble.

“Teaching students about the dangers of human trafficking is as important as teaching them CPR. You hope they never have to use it, but it’s something they should know.”

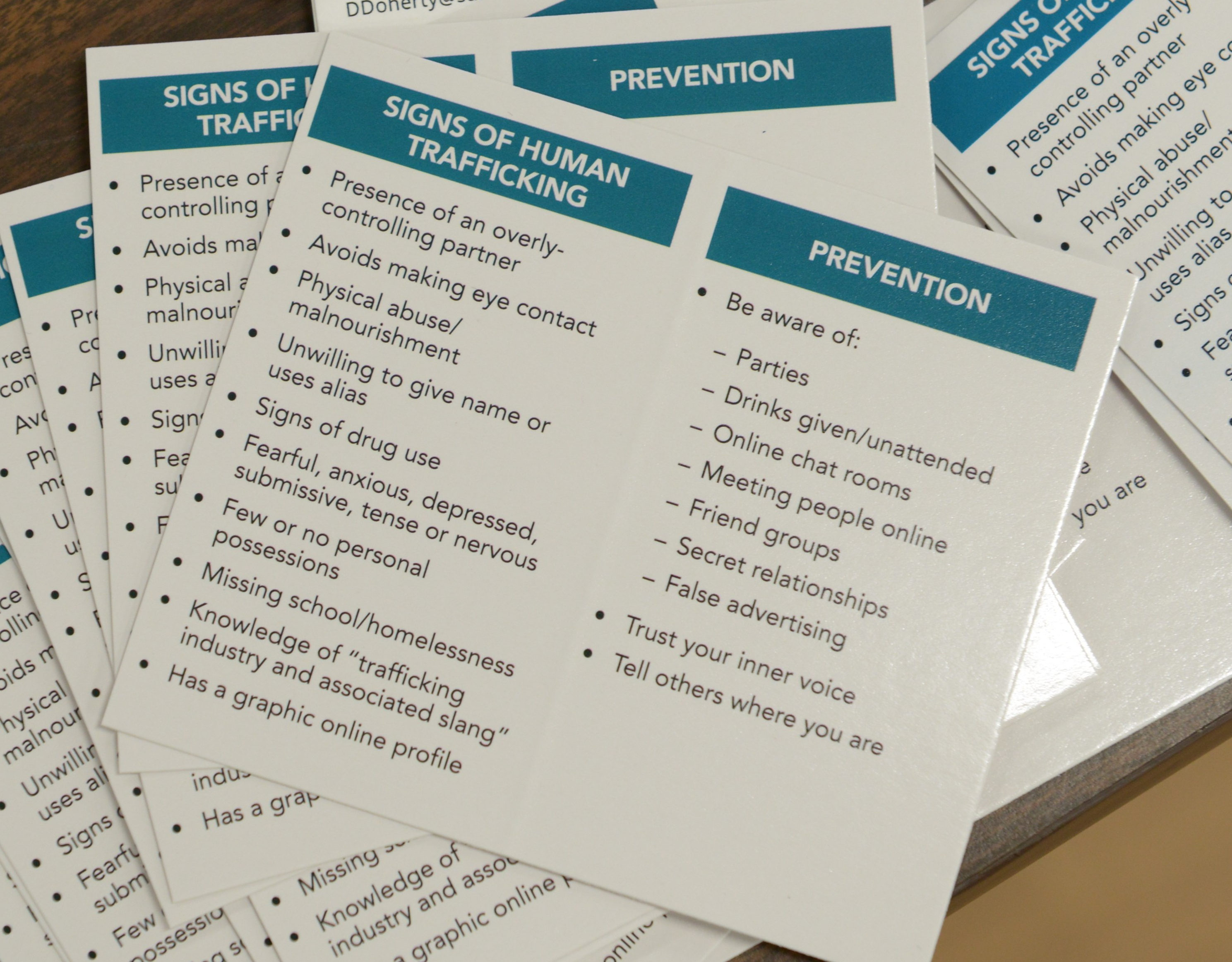

Human trafficking warning signs

How can you tell if a student may be a sex trafficking victim? According to the U.S. Dept. of Education report “Human Trafficking in America’s Schools,” signs educators should be aware of include:

- Chronic absenteeism.

- Frequent running away from home.

- A graphic online profile.

- Drug use.

- References made to frequent travel to other cities.

- Bruises or signs of physical trauma.

- Withdrawn behavior, depression, anxiety and fear.

- Hunger, malnourishment or inappropriate dress.

- Coached or rehearsed responses to questions.

- A sudden change in material possessions, such as a second cellphone, designer clothing, and other expensive items.

- A “boyfriend” or “girlfriend” who is noticeably older, or secret relationships.

- Tattoos (a form of branding) displaying the name or moniker of a trafficker, such as “daddy.” Tattoos may be hidden in the inner lip.

- Distractedness and inability to bond with others.

Easy to fall in, difficult to get out

Buki Domingos was an adult when she became a victim of human trafficking, but she knows how devastating it is for victims of any age. San Diego High School staff heard her speak at a multiday training to increase awareness about human trafficking of students.

“People’s paths are different,” says Domingos, now in her 40s. “Some choose to speak about our stories, and some stay hidden and live in fear. I like to use my story to educate others and raise awareness. I may be putting myself at risk, but it’s worth the sacrifice.”

A professional singer, she was recruited online while working as a nurse in Germany. She was asked to perform singing gigs by someone she did not realize was a human trafficker. Then came a whirlwind romance and she married him.

Participants at the San Diego High School training include school staff Sylvia Villegas, Laura Huezo, Jennifer Ruffo and Catherine Serrano.

“I realized it was a trap too late,” says Domingos. “It began as human-labor trafficking and was slowly moving into sex trafficking.” When she finally went to authorities, she says, they didn’t believe her and told her that because she and the man were married, she was a victim of domestic violence and not trafficking. She believes her credibility was called into question because she is black and her trafficker is white.

He took her passport and identification papers. She feared for the lives of her children, and he threatened her with never seeing them again if she called police. She was malnourished, isolated and terrified.

Eventually she found the strength to take her children and leave, thanks to a nurse who reached out repeatedly to help her. She stayed in a women’s shelter and reported her abuser to the authorities.

“My advice to others is simple,” says Domingos. “If something looks too good to be true, it probably is. Always do research on people before becoming involved with them.”

Teachers should be aware of red flags when once-dedicated students develop new relationships, start sleeping in class and let their grades drop, she adds.

It’s been five years since leaving her nightmare behind. She is back in nursing school and struggling financially, but free. While there has been recent attention on sex trafficking prevention and awareness, she would like to see more focus on helping victims recover.

“After everything they have been through, victims definitely need more help re-entering the world and picking up the pieces to carry on with their lives.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment