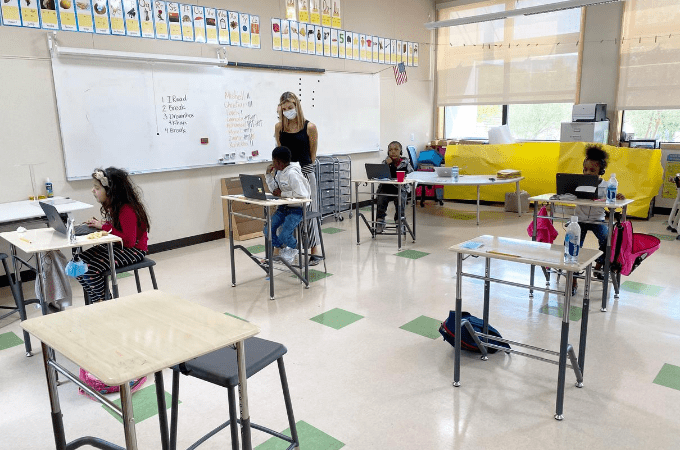

A volunteer works with Bayside students over the summer. Photo by Julia McEvoy in an original KQED story and reused with permission.

How a Sausalito school safely reopened during the pandemic

Should schools reopen or not?

It’s the biggest hot-button education issue today as the pandemic rages on. The reopening of schools has been called the “linchpin” of restarting the economy, because parents can’t work if their children are not in school. School employees worry about their own health and keeping their families safe. Meanwhile, COVID19 cases are soaring.

All California schools closed in mid-March and finished out the year with distance learning only. Except for one: Bayside Martin Luther King Jr. Academy, a Title I school located in Marin City, an unincorporated community of Sausalito where many of the students are poor and live in public housing.

(Disclaimer: The Educator is not advocating that all schools reopen by telling this story. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to teaching in a pandemic.)

Like all schools, Bayside closed after a statewide shelter-inplace order was issued by Gov. Gavin Newsom. The K-8 school, which last year had 16 teachers and approximately 120 students, tra

nsitioned to online learning. But some of the students were having difficulty engaging, especially those who lacked the parental support that helps foster success in learning online.

In a pilot project approved by the Marin County Health Department, the principal asked if any Sausalito District Teachers Association (SDTA) members would like to return voluntarily. Three said yes. Parents of struggling students were asked if they would like their children to return, and 27 students signed up.

“I wanted to come back,” says SDTA member Brandon Culley, who taught a fourth and fifth grade combination class. “I really missed the students and wanted to get back to the classroom.”

Brandon Culley

Culley is 46, in excellent health, and doesn’t have children, which factored into his decision. “But I totally understand and support the decisions of my colleagues not to go back. Many of them are in a higher-risk category and have children or are taking care of their parents. It’s a very personal decision.”

The school reopened its doors May 20 and closed for the summer June 11. Because of the small student-teacher ratio, there was true social distancing — 6 feet apart — which will likely be impossible to replicate in regular classrooms with 20 or more students. Students arrived at staggered intervals and lined up 6 feet apart on taped markings. As they entered the schools, their temperatures were taken and sanitizer was squirted into their hands. Desks did not have partitions, but everybody wore masks.

The school was open from 9 to noon daily. Students were handed a bag lunch as they exited the building. Students were grouped by grade levels, with seven to 10 students per classroom. At first, students were quiet, shy and somewhat intimidated by all the protocols in place, says Andrea Keenan, a TOSA (teacher on special assignment) who decided to return and support the students and teachers on-site while continuing her distance learning programs.

“Things were not normal,” says Keenan, a member of SDTA. “It felt weird, and students were nervous. But then it got better. These kids are super social and know each other well from living in this tightknit community. They were very happy to see each other.”

Keenan says she wanted to return because she missed having a sense of normalcy in her day and missed the kids.

Andrea Keenan

“Yes, it was scary,” she admits. “Thank goodness nobody got COVID, because I wouldn’t want to live with that. But I felt confident because there was going to be social distancing and stringent safety procedures were in place. The cleanings that took place were scheduled and posted. Back then there was very little COVID in Marin County, so I felt secure that what we were doing was OK.”

(Since then, COVID-19 has risen dramatically in Marin County, due to the transfer of COVID-infected inmates from Southern California prisons to San Quentin Prison. The inmates infected others, including staff who circulated throughout the Marin community.)

“I think it shows returning to school is possible,” says Keenan. “It requires a lot of patience and planning.”

“I felt confident because there was going to be social distancing and stringent safety procedures were in place.”

—Andrea Keenan, Sausalito District Teachers Association

Culley says it was good practice for Aug. 19, when the school is planning to reopen on a larger scale while offering distance learning for some students. “We are still going to have to figure out how to do lunches. And how to read aloud and do ‘pair shares.’ We are going to need more guidance on what’s OK and what’s not. But I think we will be able to move forward with the plan we have in place.”

That plan includes hiring more teachers to reduce the ratio of students to teachers; converting the multipurpose room, music room and art room to classroom space so students can do social distancing; and keeping students in cohorts throughout the day. Bathrooms will need to be designated and usage scheduled, as much as possible.

“We are a smaller school, so it’s easier for us to do this,” says Keenan. “These are very difficult times. Everyone is trying to do what is best for our students, ourselves and our communities.”