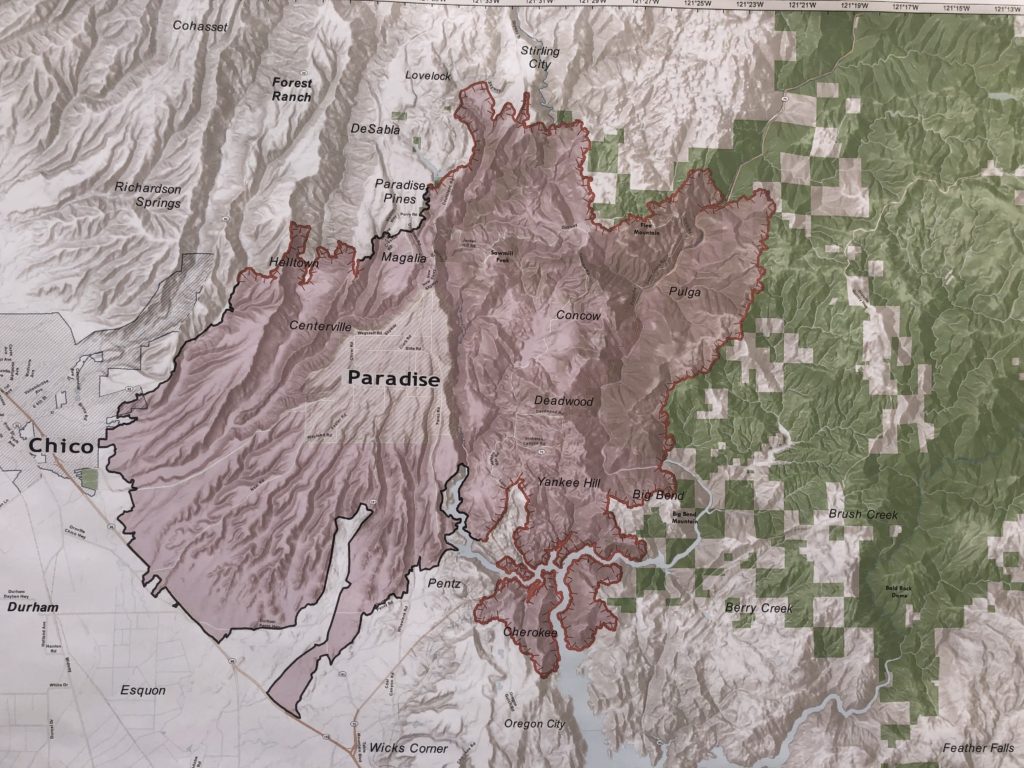

The early morning skies are clear and blue for this trip to

Paradise, a far cry from the

smoke-filled trek I made last November as firefighters battled the

devastating Camp

Fire. I’m returning to Butte County six months after first visiting three

Paradise educators whose unwavering commitment to their students was one of

many inspiring tales that emerged from the tragedy.

Paradise Children’s Community Charter School (PCCCS) teachers Brittany Bentz, Sheri Eichar and Annie Finney were constants for their students in the days and weeks following the fire, reading together over Facebook live, holding class in their living rooms and meeting up for a morning of school, fun and hugs at the Chico Library. That was where I first met these amazing teachers.

At the time, the attention of the country was on Paradise,

Magalia and other Butte County communities that had suffered the wrath of the

deadliest American fire in a century—85 people lost their lives in the disaster

and two are still missing. Donations poured in to the area, more items than the

people there could ever use. As I left the library that day, first grade

teacher Bentz said, “Hold on to the momentum of wanting to give until these

people have homes in six months. This will be a long process.”

devastating Camp Fire has left lasting impacts.

Her words have brought me back today to this still-grieving

community to see how these educators, their students and the greater Paradise

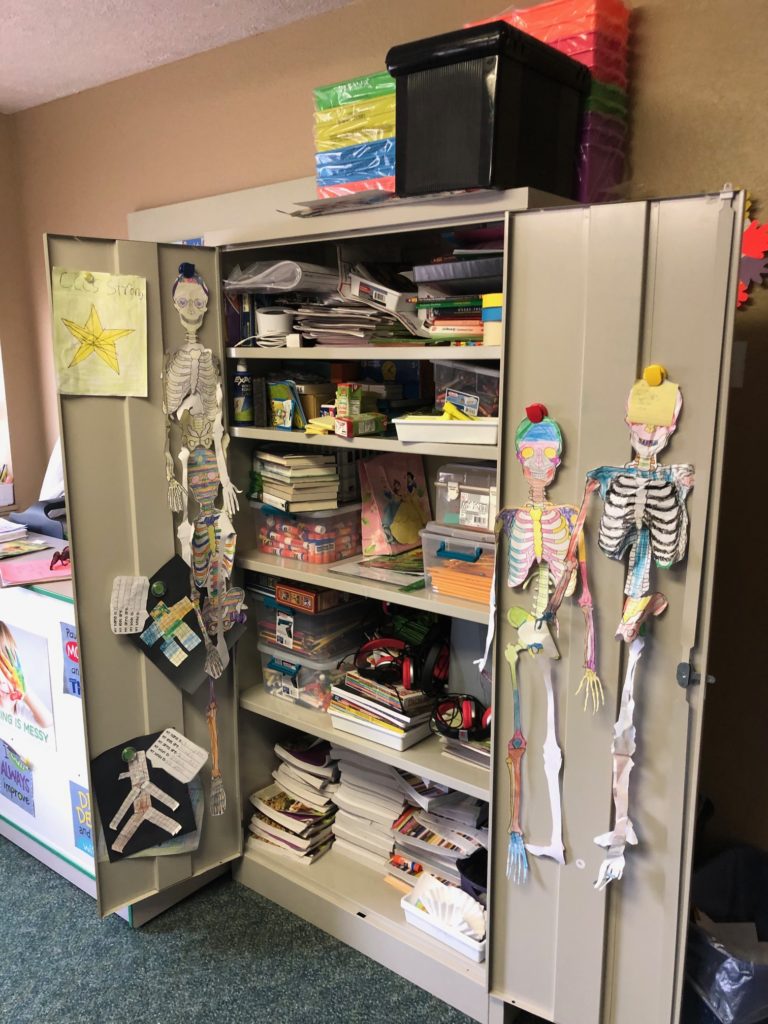

community are faring. As I walk into her classroom, Bentz notes that everything

in it was either donated or bought with donations. While they have enough items

to fill warehouses, she says, they don’t have enough of what they really need.

“We need counselors. No one can get counseling. We don’t

have any mental health services for us or the children,” she says. “A lot of

people were incredible with giving stuff. But [the general public] can’t give

affordable housing. They can’t give mental health services. We have unique

needs.”

school community waits for their school to be rebuilt after the fire.

Bentz has been tracking the many symptoms of trauma she’s observed

since the school reopened, first in a gym and now in the children’s center of

Grace Community Church in Chico. From personality changes to sickness and

exhaustion to difficulty with retention to the way they talk about their

traumatic experiences, Bentz says her students are struggling without the

services they need.

“I’m not a child psychologist. My colleagues are not

counselors,” she says. “We’re doing the best we can, but we’re teachers.”

Some of these children lived in hotel rooms for five months

after their homes were destroyed; some still live in trailers. The evacuation

of Paradise and surrounding areas added 19,000 people to Chico, putting an

unexpected strain on infrastructure. There isn’t enough housing, schools are

crowded and streets are jammed. From Highway 99, everything looks the same as

it was before the fire—the scorched earth now reclaimed by the grassy roadside

hills. But everything changes when I exit the highway to drive up the Skyway to

Paradise.

At first, I don’t believe my nose. I think for sure my mind

must be playing tricks, but I smell the fire about a mile up the ridge, just

before the burnt landscape shows itself. Dotted with charcoal trees, the

charred earth is a striking reminder of the horror that happened here not so long

ago. Massive trucks involved in the cleanup effort chug up and down the Skyway

and the billboards that line the route advertise law firms filing claims for

fire losses.

Unlike before when the area was off-limits to all but

emergency workers, I make it into Paradise. The level of destruction is

shocking. Brick chimneys stand alone in the distance like monuments to the

homes and families who once lived there. Hunks of gnarled metal, bent and bowed

from the intense heat, sit alongside the broken shells of businesses,

restaurants and residences. The scene resembles a war zone.

As I drive back down Skyway, the terrifying scenes of the Nov. 8

evacuation through a firestorm start flashing through my mind—thousands

fleeing their homes on this very route as Paradise is consumed by the blaze.

Some never made it off the Skyway, as the flames caught up to cars filled with

panic and terror. This road tells stories with no happy endings, nor one in

sight.

‘This is the most stable thing in their lives right now’

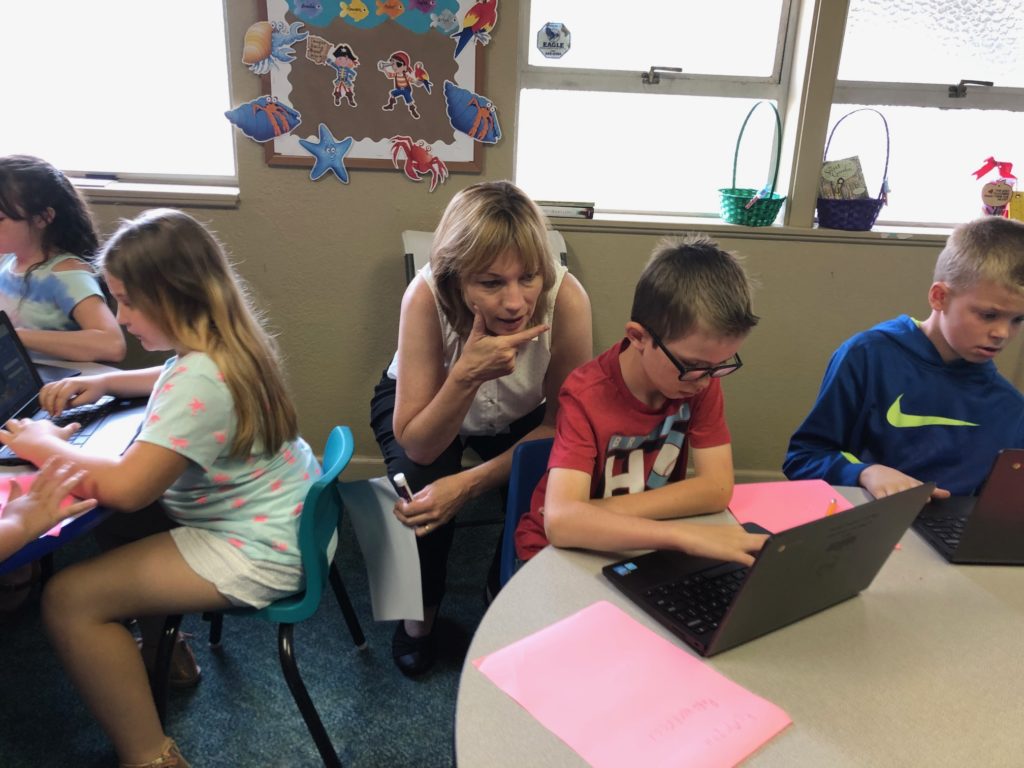

For the teachers at PCCCS, the past six months are a blur of

grief, uncertainty and keeping it together. Finney, second grade teacher and

president of Children’s Community Charter School Teachers Association (CCCSTA),

says it’s heartbreaking to see her students suffer from their traumatic

experiences. For six months, their support and love for these students and

their families has been a constant while the rest of their world has been

anything but. It’s part of what motivates them to keep pushing every day for

these kids, who don’t have the tools to cope with the ongoing situation and

whose parents are also suffering and grieving.

“They’re seeing the destruction every day. They just can’t

handle this right now, so we have to help them. This is the most stable thing

in their lives right now,” Finney says, noting that she and her fellow teachers

are also spent. “We’re kind of running on adrenaline. We’re just focused on the

kids. When summer hits, it will be tricky because we’ll have the time to think

about everything that’s happened.”

The teachers at PCCCS never know what could trigger anxiety

or panic in their students. The first fire drills when they returned to school

were unbelievably difficult, causing some students to sob uncontrollably and

tremble in fear. Just reading a book about a firefighter standing on the roof

of a home elicited upset and confused responses from the kids, who found the

image insensitive to their tragedy. Almost daily, one of Bentz’s students who

lost her pet pigs to the fire writes the word “pig” over and over again on her

assignments. A lone trauma counselor from Butte County Office of Education

splits time at a number of district schools, which is helpful but not nearly

enough for students with so many unresolved feelings after their traumatic

experiences.

Kennedy, a second-grade girl whose father heroically

evacuated a Paradise hospital, stares intently at the cover of a book about the

survivors of the tornado tragedy in Joplin, Mo. In the picture, a boy is

looking back at a heap of buildings as he flees. This, like many things since

the fire, doesn’t sit right with her.

“Don’t look back at the destruction,” Kennedy admonishes.

“Just keep running.”

While the temporary home at the church means having actual

classrooms, everyone is eager to go back to their school in Paradise, which is

being rebuilt after the fire destroyed more than half of it. It’s unknown when

the site will be safe enough to start construction and get students and teachers

on the road back to their school. Returning would mean no longer having to pack

away their classrooms every Friday afternoon so the church can use the rooms

for Bible study and then returning Sunday evening to set them back up in time

for school Monday morning. This exercise is tiring and time-consuming, but the

last six months have been a lot of extra work for these teachers, who know that

their students need so much more than familiar classrooms to get back to being

kids.

“We need to take care of trauma first. They’re not going to learn until we take care of what’s aching in their hearts and their minds.”

Sheri Eichar, Third grade teacher, Paradise Children’s Community Charter School

Eichar says trauma counselors from IsraAid, Israel’s version of the Red Cross,

came for an afternoon to share tools to help students cope, and officials from Cal Hope and the federal

public health department have also visited to provide resources. This help is

greatly appreciated but sadly not enough.

“These people come and go, but we need someone in the

classroom to help these children,” says acting principal Eichar, also a third

grade teacher and CCCSTA member.

The shortage of counselors and mental health professionals

when the

need is so great has caused Butte County Office of Education to ask retired

counselors to come out of retirement to provide these much-needed services,

with many answering the call. Following the 2017 Tubbs Fire in Santa Rosa, the

mental health needs were so great that the

local school district opened a temporary health center to provide such

resources. It’s since become a permanent community clinic, open three days

a week to provide counseling, academic support and basic nurse services, and

demand has grown as the time has passed since the fire there.

Somehow, even without the services they need, Bentz said

she’s starting to see academic growth in her resilient students. But the CCCSTA

member never knows what might set one of them off—even something as seemingly

minor as a loud noise could leave half the class in tears.

“And it’s hard because you can’t cry because you’re their

teacher,” Bentz says. “We need support too. The teachers need someone to talk

to.”

Bright Spots in the Darkness

While these teachers struggle to get their kids (and themselves) much-needed help, they are quick to note the generous outpouring of support from their CTA family and others in California and across the country. CTA members and chapters statewide donated $139,000, which was distributed in gift cards to the 335 members affected by the Camp Fire. These members also accessed CTA Disaster Relief Grants, which provide up to $4,000 in assistance to members impacted by a disaster. And then there is the special help that only educators can offer: Right after the fire, Finney said she received in the mail complete lesson plans and materials for the month of December from a second-grade teacher and United Teachers of Los Angeles member.

“She was getting ready to strike and still wanted to help us

here,” Finney says. “It was so helpful and heartwarming.”

Eichar says not a day went by for months after the fire that

there weren’t Amazon boxes on her doorstep, full of books and other items for

her students and their families. Her eyes get misty as she laments that she

wasn’t able to send a thank you note to each generous donor.

“Every single donation from a pencil to a set of books came

from a place of love and concern. Teachers have each other’s backs,” Eichar

says. “This showed me that I was not going through this alone. The support from

CTA and the nation was amazing. We knew people were thinking about us and they

cared.”

The knowledge that anyone outside of Butte County cares is a big deal to the students. Eichar says mail bags full of letters of support that arrived from around the country were especially meaningful. Outside of driving a bus full of school psychologists, counselors and mental health professionals to the area to provide much-needed services to their community, sending letters with messages of hope and love to these students is one of the best ways to help now.

“I held the letters until right before Christmas and gave

about 20 to each of my students,” Eichar says. “That was really meaningful for

them. They would say ‘Mrs. Eichar, this kid is thinking about me.’”

Mental health services for these students, their families and their dedicated educators is the paramount need though. As the school year winds to a close, the one constant they’ve had since everything changed is about to as well. And with it, some of their only real support systems. Finney says it’s difficult to watch her 8-year-olds have panic attacks and struggle with the weight of adult problems.

“I have to give them the time to deal with these things,”

she says. “I can help these kids, I can love them but counseling is not my

expertise. We need help.”

Letters for PCCCS

students can be sent to Paradise Children’s Community Charter School, P.O. Box

6729, Chico, CA 95927.

What do Paradise Students Need?

Bentz identified five major needs for her students dealing

with the aftermath of the Camp Fire:

- Small class sizes (temporarily)

- High-quality and ongoing trauma training for

teachers - Child psychologists who are available to provide

guidance and advice to educators. - Free- and reduced-price meals for all students.

- Flexibility in academic performance for 1-2

years.

Bentz has been tracking the symptoms of trauma she’s been seeing in her classroom and compiling a list of accommodations she’s made to help students cope. Her observations are available here.

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment